So it’s Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the archbishop of Buenos Aires, who will take on the name Francis (or Francesco, in Italian — or Francisco in Spanish) as the Catholic Church’s first Latin American pope — an election that recognizes the centrality of Latin America in the Catholic Church but which also shines a spotlight on the Church’s role in Latin America during the Cold War and the liberation theology that developed in Latin America, which melds church teachings with the concepts of economic and social justice.

I noted a few days ago on Twitter that, given the reticence to appoint an Italian pope, the closest thing that the conclave could have done is appoint an Argentine pope, given that Argentines have so much Italian ancestry anyway. That turned out to be more prescient than I realized.

The conclave, consisting of 115 cardinals — 67 of whom were appointed by the retiring pope, Benedict XVI, and 48 of whom were elected by his predecessor, the late John Paul II — elected Bergoglio after just four ballots. That’s the same number of ballots featured in the 2005 conclave that elected then-cardinal Joseph Ratzinger — Bergoglio, age 76, is rumored to have been the runner-up to Ratzinger in the previous conclave. He’s been a cardinal since 2001 and the archbishop of Buenos Aires since 1998.

Bergoglio is also the first Jesuit pope — as Rocco Palmo of the invaluable Whispers in the Loggia blog writes, he’s certainly more moderate than either Benedict XVI or John Paul II:

This ain’t Francis I so much as John Paul I.

Although as the Bishop of Rome, Francis is the head of state of Vatican City, the world’s smallest sovereign country, he’s now the leader of the Catholic Church to which 1.2 billion people belong — one out of every six people worldwide. Church teachings, for Catholics and non-Catholics alike, shape policy decisions throughout the world, with implications for civil rights (notably with respect to gender and sexual orientation), family planning and reproductive rights, and public health across the globe.

Latin America is home to 41% of the world’s Catholics — more than even Europe at this point — and in some ways, Bergoglio’s election can be seen as the arrival of Latin America’s centrality to global Catholicism. It’s too much to say that geography was the main rationale for selecting the next pope, of course, but it has symbolic value and certainly the cardinals in the Sistine Chapel today and yesterday knew that. With the Mormon church and protestant Christianity making inroads into Latin America, Bergoglio’s selection could both energize Latin American Catholicism and shine a light on some of the shortcomings of the Church in Latin America in previous decades.

So there’s no denying that the election of Francis I will have profound consequences on world politics — notably in Argentina and Latin America, but also in Europe and throughout the rest of the developing world.

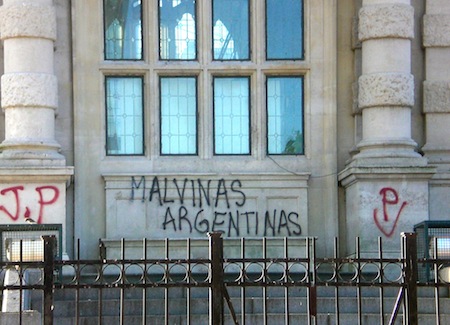

Bergoglio is a long-time resident of Buenos Aires, and he’s been intimately involved in Argentine public life. The selection will certainly shine a spotlight on Argentina, which under the rule of president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, faces a potential debt default in 2013 amid ever-tough economic times.

But it will also bring to light tough questions for Bergoglio, who’s received criticism, along with the entire Church in Argentina, for not doing enough in the light of the military junta that took control of Argentina from 1976 to 1983 that initiated what’s known as the guerra sucia (‘dirty war’) that resulted in between 10,000 and 30,000 ‘disappearances’ of various political activists:

The Argentine church has acknowledged its failure to challenge the military’s anti-leftist repression, which according to human-rights groups left 30,000 people dead or “disappeared,” including dozens of Catholic clergy and lay activists.

To the harshest critics, church leaders were not merely indifferent to the violence but complicit in it. They say that includes Bergoglio, 68, who led Argentina’s Jesuits at the time. Such charges were revived after the death of Pope John Paul II, when Bergoglio was being mentioned as a possible successor.

An Argentine tribunal in January 2013 found that the Catholic Church was complicit in those crimes:

En lo que los corresponsales calificaron como un fallo histórico, la corte dijo que la jerarquía de la Iglesia Católica cerró los ojos y a veces incluso actuaron en connivencia, ante los asesinatos de sacerdotes progresistas. Los jueces dijeron que aún hoy en día la iglesia sigue renuente a investigar crímenes cometidos durante el régimen militar. [In what correspondents described as a landmark ruling, the court said that the Catholic Church hierarchy closed its eyes, and sometimes colluded, with the murders of progressive priests. The judges said that even today the church is reluctant to investigate crimes committed during the military regime.]

As archbishop of Buenos Aires, Bergoglio has been viewed as a modernizer in pulling believers back to the Church, in the 1970s and early 1980s one of Latin America’s most conservative, following the fraught years of the guerra sucia.

In other ways, Bergoglio’s election brings to light the broader — and more uncomfortable — topic of the Catholic Church’s role in Latin America during the Cold War. Latin American Catholics developed the concept of ‘liberation theology’ — the idea that church teaching is consistent with the struggle for economic and social equality. As you can imagine, that concept was incredibly controversial during the Cold War under a pope, John Paul II, who grew up in Poland and became one the world’s most avowed foes of communism and the Soviet Union. Church conservatives at the time argued that Latin American proponents of liberation theology were hijacking church teaching in the service of third-world Marxism. Continue reading What the election of the first Latin American pope means for world politics →

![]()

![]()