After a four-day delay between Gabon’s election and the announcement of results — an interval that saw an increased military presence in the capital city of Libreville and across the country, and that brought an Internet blackout that blocked access to Facebook and other social media outlets — protestors set the national assembly ablaze Wednesday and an opposition headquarters has been bombed in what could become a sustained stalemate between president Ali Bongo Ondimba and challenger Jean Ping over Gabon’s next government.

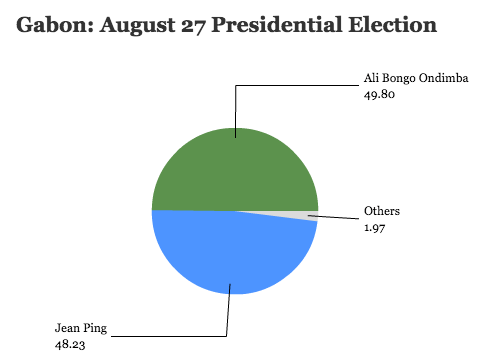

When the results were finally announced amid the tense post-election climate, Ali Bongo had won reelection to a fresh seven-year term, albeit by a narrow margin. That would sustain the governing Parti Démocratique Gabonais (PDG, Gabonese Democratic Party) in power through 2023 — incidentally, far longer than the PDG governed as the only party in a one-party state.

Gabon, a country of nearly 2 million people, is rare in that its nGDP per capita of nearly $8,300 (per the World Bank’s 2015 estimate) is far higher than most of sub-Saharan Africa, thanks to its oil wealth. That’s given the Bongo family, since the first decade of Gabon’s post-independence history, the resources to run the central African country, nudged on the western coastline south of Cameroon, as a family fiefdom. Up to a third of the country, nevertheless, lives in poverty as a result of the unequal distribution of oil profits.

Ali Bongo was first elected in 2009, following the 46-year rule of his father, Omar Bongo, who had governed the oil-rich central African country since shortly after it won independence from France.

His challenger, Ping, is a 73-year-old veteran of Gabon’s government who served as Omar Bongo’s foreign affairs minister from 1999 to 2008, president of the UN general assembly from 2004 to 2005 and who chaired the Commission of the African Union (the African Union’s executive and administrative arm) from 2008 to 2012. Ping’s father, Cheng Zhiping, was a Chinese businessman who emigrated from Wenzhou to France, where he worked for a time in a bicycle factory, and finally to Gabon, where he married and raised his family. After leaving the African Union in 2012, he turned both to the private sector and to Gabonese politics, resigning in 2014 from the ruling party and making plans to run for this year’s election. But Ping was once even married to Omar Bongo’s daughter Pascaline and had two children with her. Until two years ago, he would have represented exactly the kind of status quo that many Gabonese voters want to change. Though Ping has strong ties to China and is internationally well known, it’s not clear that his top priorities would be reducing corruption or political and government reform.

Historically Gabon has been a classic kleptocracy, and Omar Bongo ruled the country as his personal fiefdom and one of the most enthusiastic proponents of Françafrique, which normalized often shady connections between French and colonial political, financial and other vectors. French oil companies would extract Gabon’s post-independence oil wealth, and Elf Aquitaine, the former French state oil company, would some of Gabon’s oil proceeds to a special personal slush fund for Omar Bongo and the Bongo family.

While Bongo introduced multiparty elections in 1990, the benefits of incumbency (and an array of tricks to deny opposition candidates funding, to refuse equal access to media and other state resources and to deploy tribute to voters during election campaign) kept the Bongo family easily in power, even after Omar Bongo’s death in 1990.

Three factors made the August 28 presidential election in Gabon surprisingly close — and will continue to shape what could be days, months or even years of political uncertainty.

First, Ali Bongo’s hold on power is far weaker than his father’s ever was, though he served as a longtime figure in his father’s regime. Though he managed to win election after Omar Bongo’s death in 2009, it was after a closely fought contest against several officials who had also figured prominently in previous Gabonese governments. In the current campaign, Ali Bongo’s opponents claimed that he wasn’t even Gabonese — instead, a war refugee from Nigeria clandestinely adopted by Omar Bongo. The president’s supporters have dismissed it as akin to the ‘birther’ movement that inaccurately claimed US president Barack Obama was secretly born in Kenya (and not in Hawaii). Moreover, voters in 2016 may have grown weary of the Bongo family, more willing to take a chance on limited change in the form of a Ping-led government.

Second, 81% of Gabon’s export wealth — and 43% of the country’s GDP and 46% of government revenue — derives from oil. Needless to say, the past two years have been economically difficult for Gabon as global oil prices remain depressed. It hasn’t helped that China, one of Gabon’s chief trading partners, is suffering an economic slowdown and, accordingly, there’s far less demand for Gabon’s oil as well as its iron ore deposits. Ping, throughout the campaign, has attacked Ali Bongo’s efforts to diversify the Gabonese economy as widely inadequate. The problem goes even deeper for Gabon, though, because it reached peak extraction in 1997 and its oil production has steadily declined since. Gabon in 2014 was producing just 240,000 barrels of oil a day, making it the world’s 37th most oil-productive country. In a decade or two, Gabon’s oil wealth might be extinguished completely, leaving the country struggling to maintain its current level of development.

Finally, several rivals in the final days of the campaign, including former Bongo prime minister Casimir Oyé Mba and former National Assembly president Guy Nzouba Ndama, dropped out of the presidential race in a coalition designed to unite the anti-Bongo movement behind Ping’s candidacy. Under Gabon’s election rules, the candidate with the most voters wins — period. There’s no second-round runoff or the requirement that a candidate win a 50%-plus absolute majority. That gave Ping and the opposition a real chance of overtaking Ali Bongo.

Together, those reasons explain why Ping and his supporters remains so skeptical about the results, announced after several days of delay and after an ominous military mobilization that’s now in danger of tilting into widespread violence.

It shouldn’t have been a surprise to Ping’s camp that the government announced a narrow victory for Ali Bongo. Nevertheless, it shouldn’t have been a surprise to Ali Bongo’s supporters that Ping would placidly concede defeat. European Union observers said that the vote count ‘lacked transparency.’ But there’s ample evidence that the narrow margin of victory (of around just 5,500 votes) might be explained in full by possible fraud in Haut-Ogooué, the eastern-most of Gabon’s nine provinces, much of it bordering the Republic of the Congo (Brazzaville) and, most notably of all, Ali Bongo’s home province.

There, mysteriously, 99% of the electorate turned out (compared to a national turnout rate of around 59.5%) and supported Ali Bongo with 99.5% of the vote. The discrepancy makes it almost certain that Ali Bongo would have fallen short of victory in a legitimate election.

That leaves Gabon in a political state of emergency, because Ping and the Gabonese opposition seem unlikely to back down in the face of obvious electoral fraud. The question now is whether Ali Bongo is willing to deploy real force, however, in a bid to hold power at all costs.

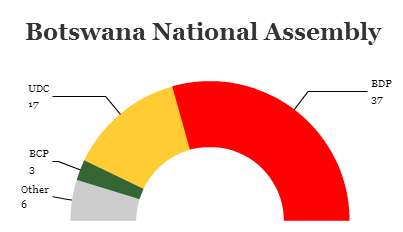

Though the idea of Gabonese democracy has made some gains since 1990, a prolonged conflict between Bongo and Ping supporters could easily erase those gains. Unlike countries like Ghana, South Africa, Senegal, Kenya and even Nigeria, Gabon’s central African neighbors have all been loathe to adopt truly competitive democracy. In neighboring Congo-Brazzaville, president Denis Sassou Nguesso, president since 1979 (excepting one term between 1992 and 1997) easily won reelection with over 60% of the vote in March after revising the country’s constitution to remove a two-term limit. Few observers have much faith in the elections scheduled for November 27 in central Africa’s largest state, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where Joseph Kabila is defying term limits to run for reelection and where leading opposition figure Moise Katumbi has already been sentenced to jail.

Photo credit to Pascal George/AFP.

Photo credit to Pascal George/AFP.