It appears that Dutch coalitions may be even easier to form now that the monarch isn’t in charge of the negotiations.![]()

Both Dutch prime minister Mark Rutte of the free-market liberal Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD, the People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy) and Diederik Samsom, leader of the social democratic Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA, Labour Party) are moving forward with talks for a coalition government, despite clear divides on some of the most important policy issues that will face the next Dutch government.

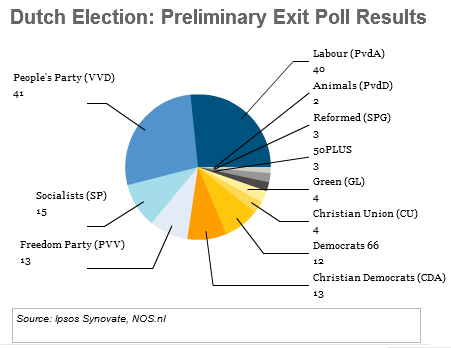

The VVD and Labour both emerged as winners by improving their existing standing in last Wednesday’s election — the VVD won 26.6% and 41 seats (an increase of 10 seats from the prior election in 2010) and Labour won 24.8% and 38 seats (an increase of eight) in the Tweede Kamer, the lower house of the Dutch parliament.

The negotiations, for the first time, following a new 2010 law, will be organized by the Dutch parliment instead of by the monarch, reducing one of the key roles that the Dutch monarch has traditionally played in affairs of state.

So instead of Queen Beatrix, VVD parliamentarian Henk Kamp has taken the lead in sorting which potential coalitions exist and now, as informateurs, Kamp and former Labour party leader Wouter Bos seem to have found enough common ground between Labour and the VVD for a potential coalition, and the camps are set to proceed with private negotiations out of the media spotlight.

Typically, it takes around three months for a coalition government to be formed — notwithstanding the new cabinet formation process that excludes the monarchy, however, it seems likely that a coalition may now be formed within weeks. That’s because there are only a small number of viable coalitions, and because both Rutte (pictured above, right) and Samsom (pictured above, left) agree that forming a relatively stable coalition quickly is important, given the questions lingering over the 2013 Dutch budget and given the precarious state of European finances.

After the 2010 election, the VVD formed a minority coalition with the Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA, Christian Democratic Appeal), with an agreement with the right-wing, populist, anti-Muslim Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV, the Party for Freedom) to provide support for the VVD agenda from outside the government. That agreement held up only until April 2012, when the PVV balked at supporting further budget cuts to bring the 2013 budget deficit within 3% of GDP, thereby causing last week’s election — the fourth Dutch election in a decade.

After preliminary inquiry into potential coalitions that began last Thursday, just hours after the election result, a so-called ‘purple coalition’ of the VVD and Labour emerged as the most likely coalition, so named because it would bring together the ‘blue’ VVD and ‘red’ Labour. The result would leave the two parties with a clear majority of 79 seats in the 150-seat chamber, but eight seats short of a majority in the upper house, the Eerste Kamer, where VVD holds 16 and Labour holds 14 of the 75 seats.

Such a coalition would be a throwback to the ‘purple coalitions’ of Labour prime minister Wim Kok from 1994 to 2002 among Labour, the CDA, the VVD and the progressive / centrist Democraten 66 (Democrats 66) (as well as a throwback to the coalitions of the 1980s between Labour and the CDA). It’s similar to the ‘grand coalition’ that governed Germany from 2005 to 2009 between Angela Merkel’s Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands (CDU, the Christian Democratic Union) and the Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, the Social Democratic Party). Continue reading Dutch talks over streamlined VVD,Labour ‘purple coalition’ progressing rapidly