For the first time since 1935, Albertans will have a government that is led neither by the Progressive Conservative Party or by its socially conservative and agrarian predecessor, Social Credit — and in its place will be a social democratic government that will not be quite as friendly to the province’s oil industry.

Ironically, when the Progressive Conservative government was supposed to lose an election in Alberta in April 2012 to the upstart right-wing Wildrose Party, it actually won a landslide victory instead, delivering a mandate to then-premier Alison Redford. When the New Democratic Party of British Columbia was projected to win a victory in Alberta’s neighboring province of British Columbia, would-be NDP premier Adrian Dix actually lost seats to Liberal premier Christy Clark in the May 2013 provincial election.

Pollsters took their hits for both Alberta’s 2012 vote and British Columbia’s 2013 vote. But they were correct in Alberta’s 2015 election, which brought to an end a record 44-year streak in government for the center-right Progressive Conservative Party.

* * * * *

RELATED: Alberta’s Prentice could fall prey to oil price collapse

* * * * *

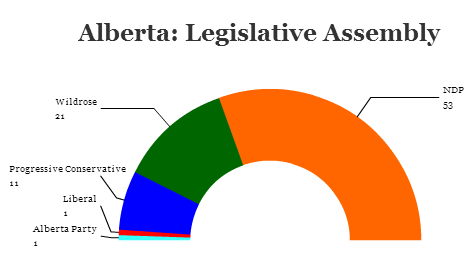

But instead of Wildrose, it was Alberta’s New Democratic Party (NDP) that emerged victorious in a landslide ‘orange wave,’ validating late polls that gave the NDP a runaway win. It’s a staggering victory for a party that’s never held more than 16 seats in the province’s 87-seat legislative assembly.

It’s also a staggering victory for Rachel Notley, who’s served as the NDP leader only since October 2014, but whose father, Grant Notley, was a popular NDP leader between 1968 until his death in an airplane crash at the age of 45 in 1984. Notley’s death came just two years before his party became the official opposition for the first time in Alberta. Sharp-tongued and competent, Notley held her own in a leader’s debate last week, demonstrating to Albertan voters that she could be trusted as their next premier.

With oil prices still depressed at around $60 per barrel, Progressive Conservative premier Jim Prentice previewed a pre-election budget that called for tough spending cuts and income tax increases in response to an anticipated $5 billion deficit for the budget. His call for snap elections now seems like a moment of hubris for a new premier that returned to politics after four years in the private sector. The decision will push the Progressive Conservatives into third place, truncating Prentice’s potential premiership by a year.

Without a doubt, Prentice will become the first political victim of the massive drop in oil prices in the past nine months.

But Prentice had always based his career in federal politics as a minister in Stephen Harper’s Conservative government, not in Albertan politics. By the time he returned, he was running at the head of a badly tarnished Progressive Conservative brand in the province after Redford was forced to resign amid scandals over the level of her spending as premier. After Redford and her predecessor Ed Stelmech seemed to pale in comparison to Ralph Klein, the 14-year premier, Prentice appeared like a return to form — especially after Wildrose leader Danielle Smith and eight other Wildrose MLAs crossed the aisle to join the PCs in support of the Prentice government. Smith, who failed to win re-nomination among the voters of her new party, will leave politics; her successor as Wildrose leader, Brian Jean, has surpassed Prentice’s PC to become the leader of the opposition. That’s an amazing result for a party that was written off as a zombie movement just months ago.

‘Grim Jim,’ as he became known in the final days of the campaign, had already conceded that Alberta is in store for a fiscal adjustment — voters decided, however, that they preferred Notley’s version to Prentice’s. Moreover, after 44 years, the damage to the PC brand in the post-Klein era was already done long before Prentice, a capable public servant, took the reins of government. Prentice, in brief remarks after the outcome, resigned not only as Progressive Conservative leader, but also as the newly elected MLA from the Calgary-Foothills constituency just minutes after Canadian news networks declared him the victor.

Notley’s NDA is expected to pursue slightly more progressive policies than the Progressive Conservatives, and they will still have to face a tricky budget deficit. With a plan to raise corporate taxes from 10% to just 12%, and with a plan to resurrect a royalty review (last enacted by Stelmech) to determine whether Alberta’s government should be entitled to a greater share of the province’s mineral wealth. In contrast to the rhetoric that painted Notley and the NDP as wild-eyed leftists, the plan is only marginally more progressive than the PC budget. Nevertheless, Notley will struggle to achieve a balance among placating business interests, raising revenues to plug the budget gap and stimulative spending as the oil-dominated economy stumbles. She’ll begin by facing a skeptical opposition, especially among Wildrose stalwarts, that believes there is still plenty of room to cut Alberta’s budget before raising taxes on corporations or individuals.

Everyone expected the NDP to do well in Edmonton, but in the tripartite nature of Albertan politics, polls as recently as 10 days ago showed that the Progressive Conservatives would hold ‘fortress Calgary’ and Wildrose would dominate in the rest of Alberta in largely rural constituencies. The reason that Notley will lead a majority government is due to the inroads that she was able to make against the PC in both Calgary and the rest of Alberta.

Notably, Notley’s opposition to the ‘Northern Gateway’ pipeline, the issue that tanked Dix’s hopes to lead an NDP government in British Columbia, didn’t harm her in Alberta. Onlookers in the United States will note that she’s ambivalent about the construction of the Keystone XL, too — while she doesn’t necessarily oppose its approval by the US government, she’s made clear that her government will not prioritize Keystone, instead focusing on the Energy East and other more feasible pipelines. Nevertheless, the promise of tighter scrutiny on the oil industry will mean a tougher regulatory environment.

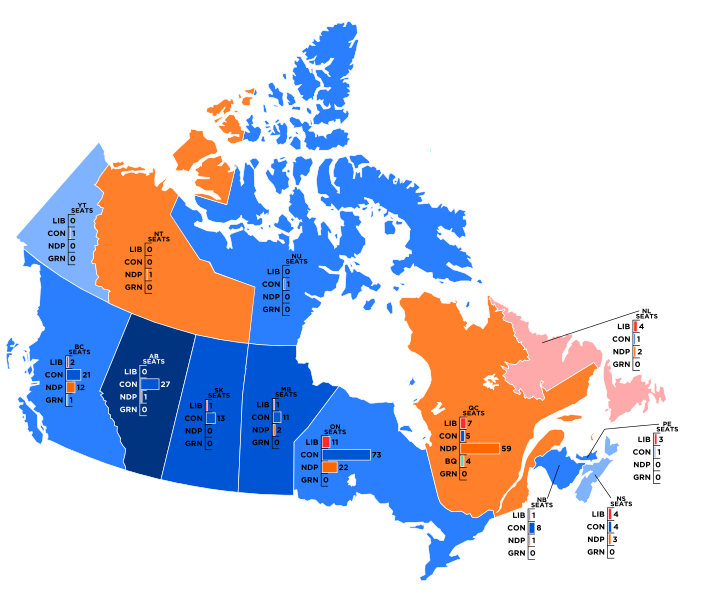

Provincial politics, as a rule, are much different than Canadian federal politics, and provincial results don’t necessarily predict future national results. Prentice’s defeat is a minor blow to Canadian prime minister Stephen Harper, who appointed Prentice as one of his top ministers until Prentice resigned from federal politics in 2010. Moreover, it leaves Newfoundland and Labrador as the only province with a Conservative or Progressive Conservative premier — and Paul Davis’s Tories are trailing by 20 to 30 points in polls as the September 2015 provincial election approaches.

It will certainly bring to an end speculation that Prentice could one day succeed Harper as the federal Conservative leader. Taken together with foreign secretary John Baird’s resignation in March, it’s good news, perhaps, for Peter MacKay, the justice minister and former defence minister.

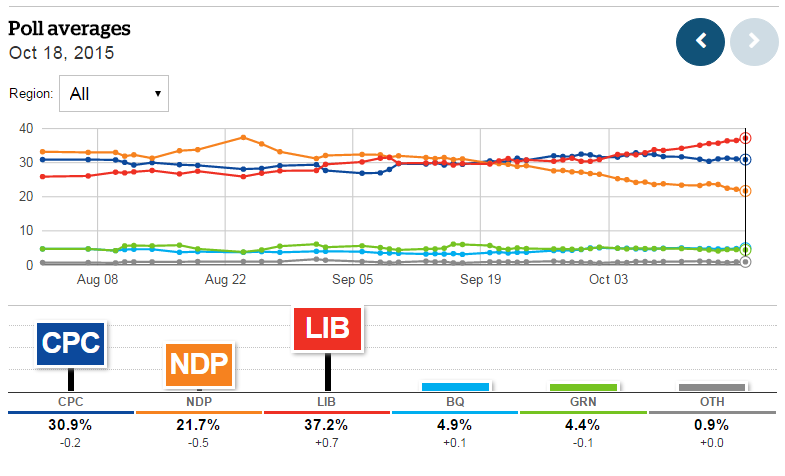

But the NDP, which is now the official opposition at the national level, has fallen behind both Harper’s Tories and Justin Trudeau’s Liberal Party. So many provincial factors contributed to the NDP victory in Alberta, including a presumably wide swing from Alberta Liberal Party supporters to Notley, mean that you should draw with caution any conclusions from the Alberta election for the October federal vote.

![]()