Moon Jae-in (문재인) was easily elected president in South Korea yesterday, following one of the most tumultuous periods in Korean democracy.![]()

Following the December impeachment and the March removal from (by a unanimous 8-0 verdict of the constitutional court) of conservative president Park Guen-hye (박근혜), who now faces criminal charges for accepting bribes, South Korea’s previously scheduled presidential election moved up from December to May 9.

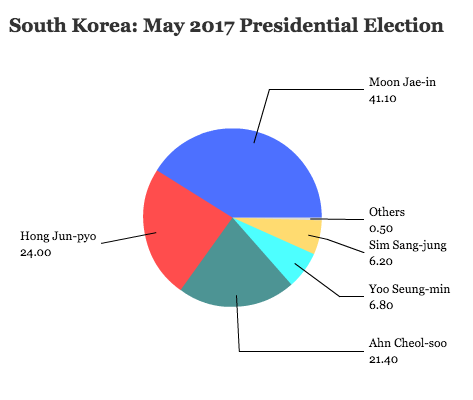

As polls predicted, Moon, the candidate of South Korea’s center-left Democratic Party (더불어민주당) easily won the presidency in a landslide against his nearest rival, Hong Jun-pyo (홍준표), governor of South Gyeongsang province, the candidate of the conservative Liberty Korea Party (자유한국당).

The election marks the end of nearly a decade of conservative rule in the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential office, and Moon has promised to bring a sweep of transparency and reform to domestic policy and a more conciliatory approach to North Korea in foreign policy.

The election marks the end of nearly a decade of conservative rule in the Blue House, South Korea’s presidential office, and Moon has promised to bring a sweep of transparency and reform to domestic policy and a more conciliatory approach to North Korea in foreign policy.

* * * * *

RELATED: Snap South Korean presidential election

points to tough Moon-Ahn race

* * * * *

Moon, a longtime human rights activist and attorney, served from 2003 to 2008 as the chief of staff, one of the leading presidential aides, to former president Roh Moo-hyun. Moon was making his second presidential run after losing the 2012 race to Park.

So what’s next? Here are the seven leading policy and political consequences from Moon’s landslide victory.

1. No honey-Moon

Due to the special nature of the election, Moon had no transition period, and he was inaugurated as president on Wednesday, just a day after the election. That gives Moon virtually no time for transitional matters as he dives into a portfolio of daunting issues, including youth unemployment, corporate reform, growing inequality, the fallout from Park’s impeachment, private and public sector corruption, the lingering North Korea threat and, of course balancing relations with an aggressive China and US president Donald Trump’s unpredictable administration.

On Wednesday, Moon nominated as his prime minister Lee Nak-yon, since 2014 the governor of Jeollanam (South Jeolla) province, a former journalist and also a member of Moon’s Democratic Party. Though the southwest has traditionally been a Democratic stronghold, it’s been less friendly to Moon, so the alliance could smooth regional and party relations.

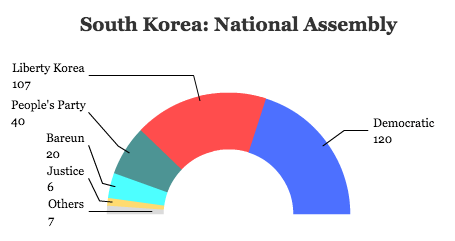

Lee’s appointment will not require parliamentary approval, but Moon will have to find a pathway to a legislative majority. Although the Democratic Party holds the largest bloc of seats in the 300-member, unicameral National Assembly (대한민국 국회), Moon is still 31 seats short of an absolute majority. Therefore, Moon and Lee will have to forge a coalition, at least on an issue-by-issue basis, with some of the 46 additional deputies from centrist and progressive parties or the six independents in the chamber.

2. Sunshine Policy redux

Moon, himself the son of refugees from North Korea, is perhaps best known for his willingness to return to the more conciliatory ‘sunshine policy’ approach to North Korean relations taken during the last two progressive presidencies between 1998 and 2008.

At a time when Trump and Chinese premier Xi Jinping are both pressing North Korea to stop testing its warheads and give up its nuclear weapons program, tensions are running as high as ever between the two countries that share the Korean peninsula.

South Korean, Chinese and Japanese officials alike cautioned against Trump’s bellicose tone last month. But Moon, more than any of his main rivals, took a less confrontational tone with North Korea. Provided that the North Korean regime doesn’t antagonize Moon or cause more tensions in the region, a Moon administration can be expected to resume humanitarian aid, diplomatic talks, economic and business ties (including reviving the Kaesong industrial park that Park shuttered in 2016) and, potentially, a meeting between the two Korean leaders — all with an eye to eventual reunification. That marks a contrast with the prior two administrations, which preferred sanctions and international isolation to force North Korea to halt its nuclear program — and the nuclear tests that began in 2006, which Trump has warned now represent a red line for US security interests:

I have great confidence that China will properly deal with North Korea. If they are unable to do so, the U.S., with its allies, will! U.S.A.

— Donald J. Trump (@realDonaldTrump) April 13, 2017

3. A rougher period for US relations

Moon’s more conciliatory approach might put him at odds with the harder line that Trump has taken with Pyongyang. But it might also provide a ‘carrot’ to the American military ‘stick’ and the Chinese economic ‘stick’ and help reduce growing tensions in east Asia. Even if Moon’s approach adds dynamism to the international community’s relations with the ‘Hermit Kingdom,’ Moon may find himself at odds with the Trump administration over other matters.

First and foremost is the hasty deployment last month of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD). Its presence on the Korean peninsula antagonizes both North Korea and China, and Moon consistently voiced skepticism of the anti-missile system’s usefulness in dealing with North Korea. The Trump administration is already demanding up to $1 billion from the South Korean government for THAAD, although Moon’s attitude toward it is ambivalent at best and although Beijing wholeheartedly opposes it.

As the election campaign unfolded in the context of Trump’s growing provocations against the nuclear-armed country and its 33-year old leader, Kim Jong-un (김정은), even the conservative Hong scolded Trump for his dishonesty (when Trump said a naval armada was headed toward the Korean peninsula; the ships were, in fact, headed in the opposite direction to Australia). Hong, who favors THAAD, nonetheless argued that South Korea couldn’t trust whatever Trump says if he continued lying about basic facts.

Moon could also clash with Trump on trade. Almost out of the blue, at the end of April, Trump threatened to scrap the decade-old bilateral free trade agreement with South Korea, arguing that it was a ‘horrible deal,’ bringing into question economic ties with South Korea’s second-most important export destination after China (which has already retaliated against South Korea because of the THAAD deployment).

Trump, by pushing South Koreans simultaneously over THAAD, North Korea and bilateral trade, risks pushing South Korea much closer to China — and away from its more traditional American ally.

4. Hopes high for economic reform

More than in 2012, Moon in 2017 emphasized a progressive platform that intends to use government to address economic gaps, from widening income inequality to employment. Young South Koreans are frustrated by the lack of employment opportunities and record-high youth unemployment of around 10%, while middle-aged South Koreans have long been frustrated by the long hours of traditional careers and managing a decent work-life balance.

Moon has pledged to raise taxes and introduce a stimulus package of up to $9 billion to boost economic performance, but he’ll first need to find allies in the National Assembly to endorse such legislation. Though South Korea’s economic gains since the end of the Korean War have been nothing short of miraculous, economic growth has slowed, just as in Japan (and increasingly in China), as the country has risen from low-income to middle-income to high-income status. Korean GDP per capita of around $27,500 is equivalent to that of European countries like Italy and Spain.

As noted above, Trump’s protectionist rhetoric could harm South Korea’s exports, and the THAAD deployment last month has chilled South Korea’s economic relationship with China, both of which could slow growth further.

Finally, while chaebol reform has topped the policy agenda for years in election campaigns, the Park scandal, and the implication of Samsung and other leading conglomerates in handing bribes to Park and her associates, inserts fresh urgency to the matter.

5. Korean conservatism is resilient

When he announced his candidacy, Hong was all but written off as an also-ran whose party — slimmed by defections and renamed in the wake of the Park impeachment — might not even survive the campaign. Other, more high-profile candidates refused to run for the presidency, including acting president Hwang Kyo-ahn (황교안) and former United Nations secretary-general Ban Ki-Moon (반기문).

Those worries were unfounded. Hong tripled his support from the levels polls showed at the beginning of the campaign. Never a close ally of Park Guen-hye, Hong rallied the conservative base in both North and South Gyeongsang, actually winning both of those provinces and in Daegu, the fourth-most populous city. He defeated Moon in North Gyeongsang by a margin of 48.6% to 21.7%.

Not only has Hong preserved the Liberty Korea Party (the party’s third name in six years) as the main party of South Korean conservatives, he managed during the campaign to win back 13 deputies from a splinter group of anti-Park conservatives that late last year formed the Bareun Party (바른정당). The Bareun presidential candidate, Yoo Seong-min (유승민), formerly a parliamentary floor leader for the Saenuri Party (the previous name of the Liberty Korea Party) won less than 7% of the vote on Tuesday.

While it was the worst showing by the traditional Korean conservative party in modern history, the cantankerous and abrasive Hong nevertheless ran an aggressive campaign on economically and socially conservative values, at once point pushing Moon into a defensive retreat on LGBT rights, in particular regarding the service of gays in the military. Hong railed against the LGBT community throughout the campaign for bringing HIV and AIDS to South Korea.

6. Ahn Cheol-soo’s career might be finished

Ahn Cheol-soo (안철수) rose to the heights of South Korean politics through the 2010s as a fresh antidote to the career politicians of the left and the right. Instrumental in electing independent Park Won-soon (박원순) as the mayor of Seoul in 2011, Ahn spent most of his career as a businessman designing anti-viral software, then as the graduate dean of Seoul National University.

Ahn first ran for president in 2012 but dropped out in favor of Moon days before the election in an ultimately futile effort to consolidate the anti-Park vote. In the ensuing years, he formed the People’s Party (국민의당) as a centrist/progressive alternative to the established parties and, indeed, threatened to overtake Moon’s Democratic Party in the April 2016 legislative elections. Think of Ahn as a Korean hybrid of Bernie Sanders, Bill Gates and Ross Perot.

As this year’s campaign began, with the Korean so right divided, Ahn was tied in polls with (or even leading) Moon. Conservative voters initially perceived Ahn as the best alternative capable of defeating Moon. Though not a conservative himself, Ahn positioned himself to the right of Moon on economic and security issues, hoping precisely to attract those conservative voters. As Hong’s supporters rallied throughout the campaign, however, Ahn flailed. Moreover, Ahn was distracted by allegations that he had flouted laws to leave his software fortune in the hands of his daughter, and voters believed he performed poorly in the presidential debates.

In a matter of days, Ahn sank from being tied with Moon to his third-place finish, amounting to a huge disappointment. Even though he ran second to Moon in many provinces, and won around a third of the vote in the southwestern Jeolla region, Ahn still trailed Moon by a margin of 42.3% to 22.7% in Seoul.

The People’s Party continues to hold 40 seats in the National Assembly, and Ahn may yet stay in politics. Though presidents are not eligible for reelection, by the time of the next election (in 2022), Ahn will have been a fixture of the political scene, not a newcomer, and several younger progressives are already waiting in the wings as would-be successors, such as Ahn Hee-jung (안희정), the 51-year-old governor of South Chungcheong province, and Lee Jae-myung (이재명), the 52-year-old mayor of Seongnam.

In the meanwhile, it wouldn’t be surprising to see his party lose steam and some of its deputies defect to the Democratic Party. Lee Nak-yon, the prime minister-designate, could be a crucial link to wooing People’s Party deputies into a formal or informal governing alliance.

7. Korean democracy is thriving

Moon, in his victory speech on May 9 and upon his swearing-in on Wednesday, pledged to unify the country — a somewhat soothing return to normality after months of political and governmental tumult.

If the Park scandal and her ensuing impeachment and removal (and pending criminal trial) presented a the most potent test of South Korea’s relatively young democracy, it’s a test that the country passed with flying colors. Critics alleged that, since winning power in 2012, Park, the daughter of Park Chung-hee (박정희), South Korea’s autocratic leader of the 1960s and 1970s, has mimicked some of the forms of political repression common in South Korea through the mid-1980s, including real threats to freedom of expression and press freedom, in particular.

Though South Korea today is one of the most developed countries in the world, with over 51 million people and the 11th largest economy in the world (nearly as large as Canada’s, with a higher GDP in 2016 than Russia, Australia, Spain, Mexico or Indonesia), its democracy remains fragile. It lags behind Japan, Australia and other developed economies in Transparency International’s corruption index, and the Park scandal and its fallout shows that corruption remains one of the most vexing issues corroding public trust.

Nevertheless, the widespread protests against Park mobilized the instruments of the Korean media, then Korean politics and, finally, the Korean judiciary and criminal justice system. In short: even under the stress of South Korea’s first presidential impeachment and removal, the system worked. As some global populations have started swinging away from liberal democracy in recent years, the South Korean example is a reminder that some emerging democracies are strengthening.