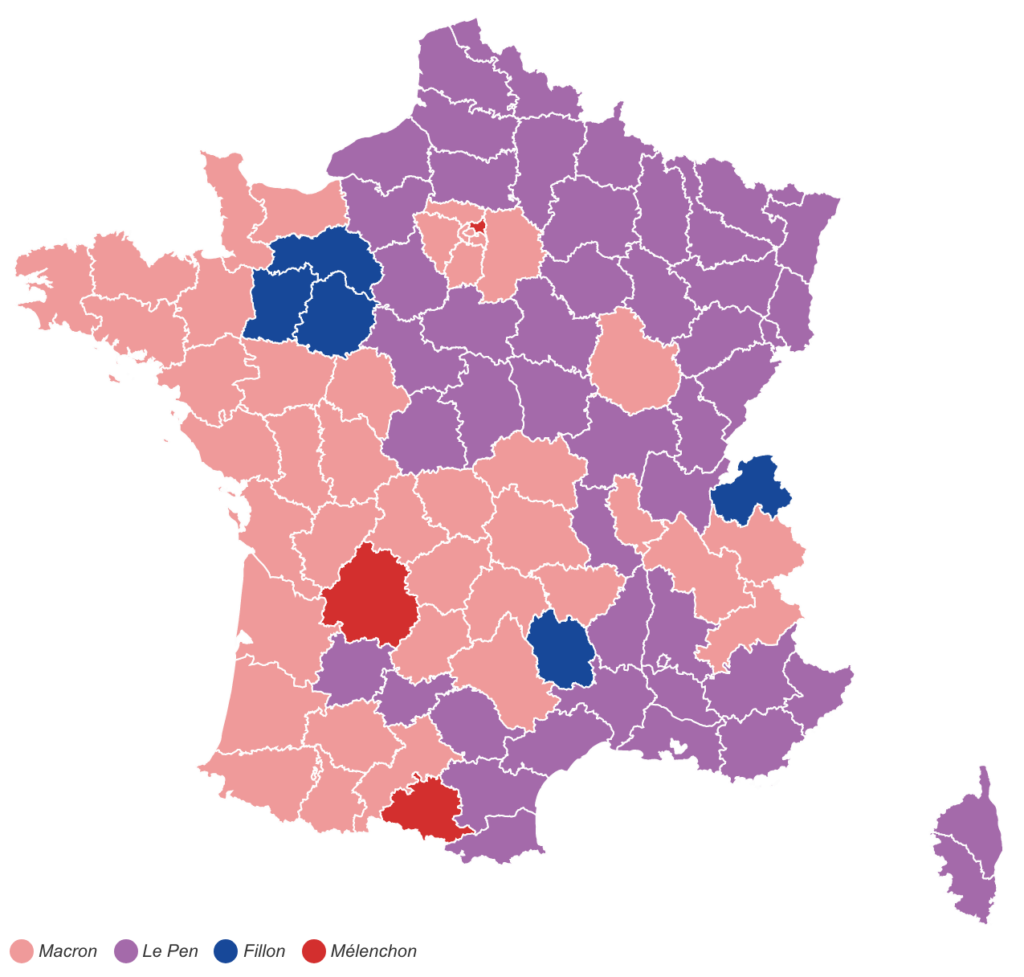

After a roller-coaster presidential election, the first-round results came with little surprise — almost exactly as pollsters predicted.![]()

French voters will choose in a May 7 runoff between two presidential contenders who increasingly embody the two dominant political views of the 2010s: cosmopolitan liberalism and protectionist nationalism.

The frontrunner, Emmanuel Macron, is a former economy minister who got his start in politics under outgoing president François Hollande and a former member of the Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party) running as an independent centrist under his formed En marche movement.

His opponent is Front national leader Marine Le Pen, who is waging a hard-right nationalist campaign opposed to globalization, European integration, immigration and the creeping influence of Islam on secular France. Though they may not carry the banners of the two major parties of French politics, in key ways, Macron and Le Pen represent less rupture and ‘more of the same.’

2017 runoff set to unfold much like 2002’s election

Almost certainly, French voters will choose Macron as their next president by a wide margin in 15 days — he has held a consistent and durable polling lead of more than 20% against Le Pen.

The third-placed candidate, former conservative prime minister François Fillon, of Les Républicains, has already endorsed Macron in the runoff (though former president Nicolas Sarkozy, sharply, has not). So has Benoît Hamon, the official Socialist candidate, and Hollande followed suit today. Former prime minister Manuel Valls, the runner-up to Hamon for the Socialist nomination in January, had already endorsed Macron in the first round. Hard-left candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon has not yet endorsed Macron over Le Pen, but Pierre Laurent, the head of France’s Communist Party, has already done so.

With just a few exceptions, dignitaries and officials from all major parties from the center-right to the far left are now rushing to form a ‘Republican front’ to support Macron, copying the playbook improvised in the 2002 election after Le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen, unexpectedly defeated Socialist prime minister Lionel Jospin into second place. (Incumbent center-right, Gaullist president Jacques Chirac defeated Le Pen in that runoff with over 82% of the vote).

So 2017 will almost exactly replay as the French election 15 years ago. By the way, a member of the Le Pen family has run for president in every presidential election except one since 1974. Since 1988, a member of the Le Pen family has won at least 10% in every presidential election. Marine Le Pen’s 21.3% support in 2017 (the supposed post-Trump era of populist nationalism) is only gradually more than the 17.9% she won in 2012 (the supposed Obama-Merkel era of pluralistic internationalism).

None of this is effectively ‘new’ in French politics.

Center-right Republicans could still win legislative elections in June

With a near-certain win in the May 7 runoff, Macron must now look to the more important (and more difficult) June parliamentary elections. Again, digging down into the fundamentals of that election shows more continuity than meets the eye.

Without control of the Assemblée nationale (National Assembly), Macron’s presidency will be stillborn. Macron will only command real power if En marche wins a majority in June or manages to lead a coalition that commands a majority. All 577 deputies in the National Assembly will be chosen in two rounds of voting on June 11 and June 18. Macron has committed to identifying 577 candidates to run under the En marche banner, half of whom he hopes will be women and half of whom will be new to French politics — meaning that the remaining candidates may come from existing Socialist, Republican or centrist ranks of the political elite).

The outcome of those elections remains distinctly unclear, as there’s not a lot of polling data. But it’s a solid bet that the Republicans and even the Socialists (in one form or another) will perform better than in yesterday’s presidential vote.

Perhaps the breakdown in two-party hegemony will lead to more triangulaires or quadrangulaires (three-way or four-way runoff contests) on June 18, giving Le Pen’s Front national and Mélenchon’s hard left a greater chance to win more seats than in past legislative elections, when the runoff system’s effects have been particularly brutal for third parties. But such predictions have failed in nearly every legislative election of the Fifth Republic.

Of course, it’s also possible that the Socialist Party will collapse and that En marche will become the new party of the center-left. If that happens, however, it will be because many Socialists simply exchange their PS membership cards to suit up as En marche candidates. That looks less like rupture and more like reinvention. It’s not unlike when François Mitterand rebuilt and rechristened the Section Française de l’Internationale Ouvrière (French Section of the Socialist International) as the modern-day Socialist Party after the 1969 election — when the SFIO candidate won even less support (5%) than Hamon won (6.4%) in the 2017 race.

It’s also equally plausible that the Republicans (who will not wage the legislative campaign under Fillon’s leadership) will win a plurality or even a majority of the vote, forcing Macron to ‘cohabit’ with a center-right prime minister (Sarkozy!?) or to negotiate a centrist coalition of En marche and Republican deputies. Had the Republicans not nominated Fillon, a scandal-ridden figure under investigation for fraudulently paying hundreds of thousands of euros to his wife in public funding for ‘fake jobs,’ the Republican nominee would have likely advanced to the May presidential runoff.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même

In a cosmetic sense, it’s revolutionary that France’s top two presidential contenders both come from outside the two traditional parties that have generally (but not always) dominated French politics in the Fifth Republic. But it’s foolhardy to say that the old parties no longer matter, because they most certainly will in the June elections.

Moreover, parties have been weak throughout the Fifth Republic. For years, the French right split between Gaullists, who espoused a big-nation, Catholic conservatism (Charles de Gaulle himself and Georges Pompidou), and centrists who embraced free-marker liberalism (Alain Poher and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing). Just as Mitterand transformed the SFIO into the modern Socialist Party (and just as Macron may be transforming the Socialists into En marche), the French right has transformed from the Gaullist ‘Union for a New Republic’ in the 1950s and 1960s to the ‘Rally for the Republic’ in the 1980s and 1990s to the ‘Union for a Presidential Majority’ in 2002 to the ‘Union for a Popular Movement’ in the Sarkozy era to the Republicans today.

Note, also, that more often than not, French communists in the Fifth Republic have always run a candidate against the SFIO/Socialist candidate in first-round presidential elections. That includes the Socialist high-water mark, Mitterand’s victory in 1981 (when Georges Marchais still won 15.4% of the first-round vote). So the intellectual and ideological divides between Macron and Mélenchon, or even the divides between Valls and Hamon, are nothing new in French politics.

It’s true that the runoff presents the French electorate with a cosmopolitan technocrat, an economic and social liberal who embraces the European Union, globalization and immigration as vital to France’s role in the 21st century versus a nationalist who would close French borders to ever greater immigration, trade and influence from Brussels. The former, who comes from the ‘left’ tradition, has nevertheless embraced neoliberalism, free trade and pro-business policies; the latter, who embodies the ‘far right,’ is increasingly at ease with the kind of protectionism and big-state nationalism once dogma of the hard left. If western democracy is moving away from a politics where the key ideological battle is nationalism versus globalization, and not left versus right, the Le Pen-Macron runoff proves the point neatly, and both candidates have scrambled what we once thought as strictly rightist or leftist.

But don’t get carried away.

Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, running as a hard-right Gaullist, won nearly 5% of the vote. Two hard-left candidates, Nathalie Arthuad and Philippe Poutou, together won 1.75%. If the former’s supporters would have otherwise voted Fillon and if the latter’s supporters would have otherwise voted Mélenchon, the narrative from the first round would be much different, because we would be facing a May runoff between Fillon (a mix of economic liberalism and social conservatism) and Mélenchon (a mix of economic leftism, social liberalism and euroscepticism). So to the extent that we see in the Le Pen-Macron showdown a ‘new’ paradigm of emerging politics, we should also admit that even a few hundred thousand votes would upend that analysis.

Moreover, Le Pen and Macron increasingly resemble the ‘mainstream’ in French and European politics and Macron, in particular, is an avatar of the political elite that voters claim so much to despise.

Though Fillon and Le Pen differ widely on economic policies, Fillon (and before him, Sarkozy and conservatives like Jean-François Copé) have inched for a decade ever closer to the Front national‘s rhetoric and policies on immigration. Le Pen is far more anti-EU than Fillon, and she would lower the retirement age, while Fillon (as Sarkozy’s prime minister) raised it from 60 to 62. But in the closing weeks of the first-round election, Fillon de-emphasized a radical vision of free-market economic reforms in favor of a stronger line on security and immigration. The speed with which Fillon endorsed Macron shows that there’s still a cordon sanitaire between the center-right and the far right in France. But for a decade, as Le Pen has worked to excise some of the worst anti-Semitism and xenophobia from her father’s party, and as the Sarkozy-Fillon right have embraced a sharper tone on migration (which last November easily defeated the more moderate approach of former prime minister Alain Juppé), that line has become increasingly blurred. That trend seems likely to continue — juppisme doesn’t feel like future of the French right.

Macron, meanwhile, for all the talk of change and independence, is a paragon of the French political elite, a product of all the standard schools, banks, government agencies and top circles that have traditionally produced the French political elite. With Hamon campaigning on universal basic incomes and ‘post-work’ taxes on robotics, many top Socialists were far more comfortable with Macron, who might as well have been the unofficial candidate of the Socialist Party. Indeed, many familiar Socialist faces will almost certain run on the En marche line in June’s legislative elections. Macron got his start politically as a deputy chief of staff to Hollande, and his chief qualification for the presidency is a two-year stint as Hollande’s economy minister, when he tried, with some success, to liberalize France’s economy. For all the talk of change and upending the system, Macron represents Hollande’s second term — a bridge to the status quo.

The tectonic plates of French politics are undoubtedly shifting. But those changes are playing out gradually and in ways that are consistent with electoral and political trends throughout the Fifth Republic. Whether those trends continue depends largely on whether a Macron presidency can deliver on promises of a new kind of government. Macron’s failure over the next five years to drive down unemployment or prevent deadly terrorist attacks could correspond to more support for the extreme right or the extreme left. But Le Pen and Mélenchon (and their predecessors) have always been in the mix of French politics and will certainly continue in 2022 and beyond.

NOTE: This piece originally stated that Fillon is accused of diverting hundreds of millions of euros to his wife; in fact, it is hundreds of thousands.

(Fillon) “fraudulently paying hundreds of millions of euros to his wife in public funding for ‘fake jobs…”: actually it was less than a single million dollars over 7 years, for a salary of legislative assistant, not “hundred of millions”.

Furthermore, while this practice is frequent (over a hundred French members of parliament are reported to employ family members as legislative assistants) and while it is ethically dubious (Macron and others have said they will propose legislation to forbid this), it is a very modest and marginal ethical violation compared to the massive “pay for play” system which structurally prevails in the US, amongst other countries, between politicians, businesses and various lobbies.

*thousands. My fingers were faster than my brain on this one.

It is odd that there is still so little legislative polling despite the unusually high degree of importance that the legislative elections will take on this year. It would seem unimaginable that En Marche would get a majority on its own unless a huge amount of incumbents flood into the party (but that is problematic).

I am wondering, if, with so many parties fielding candidates that winning pluralities will often produce huge margins for a party that consistently sees its candidates reach the second round. Could this help the Les Republicains Party as it would seem to be the party with the single biggest support base at the moment?