If 2016 was the year when global politics fully embraced populist nationalism, 2017 will be the year when we learn just how successful that approach might be.

In a series of contests across western Europe, the choices that voters make in 2017 will determine the future migration and immigration patterns of a continent and the kind of future the European Union holds as an institution.

Moreover, no one knows quite what to expect when Donald Trump is inaugurated on January 20 in the United States as the country’s 45th president, following a campaign during which Trump reveled in ripping up the norms of American domestic politics and international affairs alike. That volatility could lead to any number of outcomes — a sharp anti-American trend throughout the world, or a folllow-on effect where world voters look to find nationalist Trump-style champions of their own, as the traditional left-right divide in global politics increasingly gives way to a deeper fight between nationalism, often populist, mercantilist and in some cases illiberal, and internationalism, rooted in the kind of economic and social liberalism that has dominated the democratic world since World War II.

That means that 2017 might be one of the most unpredictable years in world politics since the end of the Cold War, as an American-dominated unipolar world increasingly gives way to a multipolar world with new spheres of regional influence.

So what elections should you be watching across the globe this year?

Here are the Suffragio 17 in 2017.

1. Uttar Pradesh: January/spring

legislative assembly elections

Despite the talk about the rise of the hard right in the United States and Europe, there’s a case to be made that the most important election in 2017 is the regional election in Uttar Pradesh, which will take place over several stages early this year.![]()

With well over 200 million people, the single state is home to more people than all but five countries worldwide. Uttar Pradesh is, on balance, less developed and less wealthy than India as a whole, and its relatively large Muslim population means that the state has suffered from religious tensions over the years. It’s also just one of seven regional elections set to take place in India this year — Modi’s home state of Gujarat will also select a new government, as will Punjab, where the BJP governs as the junior partner of a Sikhist-led party.

Moreover, as in the 2014 general election, Uttar Pradesh presents a key test for Narendra Modi three years after that wave election brought Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) into government and two years before Modi will seek reelection. Just months after removing the 500- and 1,000-rupee notes from circulation, the Uttar Pradesh states elections will be a referendum on the Modi approach to digitalizing and reforming India’s economy, however slow-going his legislative efforts may be.

Up for grabs are all 404 seats in the Vidhan Sabha (उत्तर प्रदेश विधान सभा), the lower house of the state’s bicameral legislature.

Politics in Uttar Pradesh are notoriously complex because of the religious and caste balances at play, and the BJP competes not only against the Indian National Congress (Congress, or भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस), but against two local parties that have traditionally drawn support from both Muslims and lower castes, the Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP, बहुजन समाज पार्टी) and the Samajwadi Party (SP, समाजवादी पार्टी).

For the last 15 years, the BSP and the SP have seesawed into and out of power.

Since 2013, the Samajwadi Party has held a lopsided majority in the regional assembly, but internal struggles between its longtime leader Mulayam Singh Yadav and his son, chief minister Akhilesh Yadav have divided the party nearly to the breaking point. Congress, still reeling in the wilderness after its national 2014 losses, seems set to place far behind in fourth place, barring some alliance with the Samajwadi Party (or a breakaway faction, at least).

Polls currently show that the BJP is locked in a three-way race with the Samajwadi Party and the BSP, with perhaps a slight edge to win the greatest number of seats. That means there’s a great chance that Uttar Pradesh could end up with a hung legislative assembly and a coalition govenrment. That’s given former chief minister Mayawati, once a rising star in Indian politics, a shot at returning to government if she can mobilize supporters with a wilting Congress and a fragmented Samajwadi Party. Though Mayawati herself comes from the dalit class, she has suffered accusations of corruption and using power to enrich herself and her family.

It’s puzzling that the BJP hasn’t made clear its choice for chief executive, a problem that dogged the party in its failed effort to unseat the popular Nitish Kumar in Bihar’s state elections in late 2015. It’s also puzzling why the Congress continues to meander under Rahul Gandhi’s leadership when his sister, Priyanka Vadra, is so much more charismatic.

Ultimately, control for India’s most populous state could come down to a fight between Modi’s controversial and often divisive vision of development and the kind of populist and patronage-heavy client-state arrangement that has typically dominated regional government.

Bottom line: If Modi and the BJP thrive in Uttar Pradesh this year, it will be a very good sign for Modi’s reelection hopes in 2019. If there’s a BJP rout, it could be a qualified endorsement for demonetization and Modi’s Hindutva-influenced reform approach. A disappointment for the BJP here, like in Bihar in late 2015, however, need not spook BJP leaders if it’s a vote in favor of local leaders and not, strictly speaking, against Modi. Will a Rahul Gandhi-led Congress ever be relevant again?

2. The Netherlands: March 15

parliamentary elections

For now, Geert Wilders is running a campaign that looks and feels much like the Trump campaign, complete with a slogan of making The Netherlands Great Again, emphasizing euroscepticism, opposition to immigration and, above all, antipathy to Islam as a religion incompatible with the Dutch tradition of tolerance.![]()

And so far, Wilders seems to be winning.

But for all the hand-wringing over Wilders and his hard-right Partij voor de Vrijheid (PVV, Party for Freedom), he is very unlikely to win the kind of landslide that would entitle him to form a government on his own. Even the most optimistic polls give the PVV just 35 seats in the 150-member Tweede Kamer, the Dutch House of Representatives. So even if the PVV winds up in first place, its toxic reputation means it will not find coalition partners and therefore, cannot realistically form a government.

Far more likely? Mark Rutte, who is running for a third term as prime minister as the leader of his own center-right, liberal Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie (VVD, People’s Party for Freedom and Democracy), will head the next government, even if Wilders and the PVV win more seats.

The problem is that Rutte’s coalition partners, the Partij van de Arbeid (PvdA, Labour Party), are projected to drop from 38 seats in the current parliament to 10 or fewer after dominating the 2013 election on a generally anti-austerity and center-left platform. When Labour joined Rutte’s budget-conscious government, however, it quickly lost much of its support, especially after Labour finance minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem became the face of Europe-wide austerity as the president of the Eurogroup in January 2013. It’s unlikely that Labour alone — even under its new leader Lodewijk Asscher — will lift Rutte to a majority.

So Rutte will have to cobble together a coalition of disparate allies, including perhaps what’s left of Labour and the reform-minded Democraten 66 (Democrats 66), a left-liberal group that surged in the 2014 municipal elections. That might still not be enough, and Rutte might have to turn to a fourth or fifth party, such as the more right-wing Christen-Democratisch Appèl (CDA, Christian Democratic Appeal), Rutte’s first-term coalition partners.

One note of caution — in the last election, the Socialistische Partij (SP, Socialist Party) spent much of the summer with a wide lead in polls, only to plummet in support after Dutch voters started paying more attention to the campaign and the leaders’ debates. Voters who say they are willing to vote for Wilders today may change their minds as the election approaches and as Rutte and other party leaders continue to take an increasingly tougher line on immigration.

Nevertheless, even if Wilders’s support holds, it is unlikely he’ll become prime minister in 2017. The risk for the Dutch political spectrum is that a four- or five-party Rutte-led coalition will leave little in the way of opposition for the next election, giving Wilders an even bolder claim on the mantle of ‘change.’

Bottom line: You shouldn’t worry about a Wilders-led government in 2017, but if he commands 30% or more of the Dutch electorate, it’s hard to say his hard-line views are ‘extreme.’

3. Hong Kong: March 26

chief executive elections

When the British officially restored Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty two decades ago, 2017 was supposed to be the year that Hong Kong’s residents would at long last enjoy universal suffrage as part of what Deng Xiaopeng (邓小平) described as ‘one country, two systems.’ ![]()

![]()

But as the widely unpopular Leung Chun-ying (梁振英) steps down after a rough five-year term as chief executive, his successor will continue to be chosen by the 1,200-member election committee of local leaders and other business figures. That follows the failure of a Beijing-led initiative to introduce a controlled democracy whereby a nominating committee would select two or three nominees from which the Hongkongese electorate might choose.

Pro-democracy activists, however, occupied central Hong Kong in 2014 in opposition to the measure, arguing that it gives Beijing far too much control over Hong Kong’s affairs. The net result is that while the protesters defeated the new measure, the current system (where just 1,200 individuals choose the chief executive) remains in place. That result already has activists marching in the new year, and the March election could force a showdown with Beijing.

Several candidates are running (or are expected to run) in the chief executive election. Beijing is certain to want the elections committee to choose a unifying figure after Leung, and one of the early frontrunners is 65-year-old John Tsang Chun-wah (曾俊華), a seasoned veteran of past administrations. He served as Hong Kong’s financial secretary, the most important economic policymaker in the special administrative region, from 2007 until his resignation last month, presumably in advance of a run for chief executive. Tsang’s experience in Hong Kong affairs goes back to the British colonial era, when he served as private secretary to Chris Patten, the last governor-general. Tsang already has the endorsement of Antony Leung Kam-chung (梁錦松), a former financial secretary, and there are hints that he is emerging as perhaps the most harmonious compromise.

Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor (林鄭月娥), the 59-year-old incumbent chief secretary, a pro-Beijing official close to Leung, is also likely to run. So might Jasper Tsang Yok-sing (曾鈺成), the 69-year-old former president on the Legislative Council, a more liberal figure from the pro-Beijing camp. Other candidates include Woo Kwok-hing (胡國興), a 70-year old deputy judge and Regina Ip (葉劉淑儀), a 66-year-old pro-Beijing veteran of the executive and legislative councils.

No one expects any stridently pro-democratic candidates for chief executive to win, despite gains by activists in last September’s legislative election. But while Jasper Tsang and John Tsang enjoy relatively more popularity than the rest of the potential field, they remain Beijing loyalists. Indeed, in the 2012 chief executive election, Leung won power because he was seen as more sympathetic to Hong Kong than his opponent, though he mostly hewed to the official line once elected and walked an impossible line between Beijing and the ‘Occupy’ activists in 2014.

Bottom line: Beijing is casting about for the most conciliatory candidate to lead Hong Kong, but it will brook little dissent from pro-democracy activists, whose protest might yet force a conflict with mainland officials.

4. France: April 23 / May 7

presidential elections

So far, the story of the 2017 French presidential election is the rise of Marine Le Pen as a credible threat to make the final runoff between the top two candidates.![]()

But with former president Nicolas Sarkozy defeated in his bid to lead the center-right Républicains and unpopular incumbent François Hollande ruling out reelection as the candidate of the center-left Parti socialiste (PS, Socialist Party), the real story of France’s 2017 vote might be the expedited decline of its traditional two-party system. Anywhere from four to six candidates have a realistic chance of making it to the second-round runoff that will determine the country’s leader for the next five years.

Though the Socialists will choose its candidate later this month,they could fall behind to fifth place or worse, even without the toxic and ineffective Hollande leading the ticket. The most likely Socialist nominee is former prime minister Manuel Valls, also a former interior minister and an economic liberal on the party’s right wing. For now, his chief competition is Arnaud Montebourg, an economic populist best known for trying to protect French industry from foreign investment as Hollande’s former economy minister. Though Valls typically polls better in the April election, expect the race to tighten as the end of the month approaches. (Also keep an eye on Benoît Hamon, a one-time Montebourg protégé, who could emerge as a consensus third-way candidate).

On the right, former prime minister François Fillon won the Républicain nomination over Sarkozy and former foreign minister Alain Juppé after what seemed like an overnight surge. Fillon, now a slight frontrunner to win the presidency, will run on an economically conservative platform, figuring high on tax cuts and Thatcher-style market reforms, while appealing to the kinds of Catholics and traditional social conservatives that Le Pen and the hard-right Front national also need to win. Le Pen, for her part, has shown some success in winning over not only right-leaning voters, but former Socialist voters, especially in the de-industrialized and depressed French northeast. Both Valls and Fillon, like Sarkozy before them, have tried to co-opt the rhetoric and even the policies of Le Pen, which could undermine her message.

Nevertheless, Emmanuel Macron, a former banker and Hollande’s former economy minister, is surging in the polls as an independent candidate, hugging the center and (like Valls and Fillon) the vague notion of ‘reform.’ Perennial challenger François Bayrou of the centrist Mouvement démocrate (Democratic Movement) could also crowd the center.

If Valls defeats Montebourg and Hamon for the Socialist nomination, Jean-Luc Mélenchon of the Front gauche (Left Front) will be virtually the only significant hard-left voice in the election. With Fillon and Macron and, possibly, Bayrou and Valls, all vying for the centrist, ‘reformist’ mantle, there’s a chance that Mélenchon — many of whose supporters reluctantly voted for Hollande in 2012 — could rise as the progressive voice of disenchantment of the French left.

Today, it is likely that either Fillon or Macron will advance to win by a lopsided margin in the runoff against Le Pen, though yet another terrorist attack or another black-swan event could scramble that logic, giving Le Pen a boost. It is also plausible that Fillon and Macron both advance to the runoff, leaving Le Pen in a disappointing third place in a particularly impressive victory for the political mainstream. But there’s also a chance that with so many candidates in the middle, France’s voters will face an ‘extremist’ runoff between Le Pen’s hard-right eurosceptic and xenophobic vision and Mélenchon’s unabashedly populist and left-wing vision.

Bottom line: French voters trust the two-round system as a safeguard against an extremist like Le Pen winning the presidency, but don’t expect a Chirac-style rout in May. Keep your eyes, too, on the parliamentary elections that follow shortly in June.

5. Iran: May 19

presidential election

Since the birth of the Islamic Republic in 1979, no Iranian president has failed to win reelection.![]()

What was true for Ali Khamenei (now Iran’s Supreme Leader), the wily Hashemi Rafsanjani, reformist Mohammad Khatami and conservative Mamoud Ahmadinejad now appears likely for Hassan Rowhani, who won the 2013 election in a landslide first-round victory. In four years, Rowhani has worked to balance the expectations of his liberal supporters with the realities of the conservative actors that otherwise control the Iranian state, including a skeptical Khamenei.

Rowhani’s chief accomplishment is the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), the nuclear deal agreed in 2015 with the United States, China, France, the United Kingdom, Russia and Germany that lifts sanctions on Iran in exchange for the near-elimination of Iran’s uranium stockpiles and regular access to Iranian nuclear energy facilities. The implementation of JCPOA has been fraught with difficulties in Iran, and the incoming Trump administration (not to mention Benjamin Netanyahu’s government in Israel) are highly skeptical of the deal, at best. There’s some doubt as to whether the Obama-era agreement will endure long into the Trump era.

Furthermore, JCPOA alone hasn’t unlocked the kind of instant economic turnaround Tehran might have hoped, including Iran’s anticipated integration into the global economy. Frustrations about the lack of an economic boom could embolden Rowhani’s conservative and hardline ‘principlist’ opponents. Those include Ahmadinejad, who is rumored to be interested in an uphill bid to return to the presidency. Ahmadinejad’s gradual falling out with hardliners since his second term, however, could complicate his ambitions, as Khamenei has instructed Ahmadinejad not to attempt another run. Qassem Suleimani, a popular general of the elite Quds Force within the Revolutionary Guards, ruled out a run in late 2016 as well. Other, more capable conservatives may emerge, including former nuclear negotiator Saeed Jalili, once seen as a frontrunner in the 2013 election.

Rowhani must also face disappointment from his most progressive supporters, who certainly hoped for much more cultural easing in Rowhani’s first term or, at a minimum, the release of 2009 presidential candidates Mir-Hossein Moussavi and Mehdi Karroubi. Leading reformists, like former presidents Rafsanjani and Khatami, both support Rowhani’s reelection, however, and it seems unlikely that another reformist to Rowhani’s left will emerge as a significant challenger.

Perhaps the more pressing question for the Islamic Republic isn’t whether Rowhani wins reelection, but whether he can achieve the kind of economic reforms Iran truly needs to become more compatible with the global economy. Parliamentary elections last year, seen as a victory for reformists, give Rowhani a more favorable path. But Khamenei could block all of it, and two-term Iranian presidents have a history of accomplishing little. Another question looming over a second Rowhani term is whether the 77-year-old Khamenei (only the second Supreme Leader in the country’s history) will survive. Though Khamaenei’s successor is not likely to be a liberal, the transition to a new Supreme Leader could give Rowhani a stronger hand vis-a-vis Iran’s conservatives.

Bottom line: Rowhani is clearly a favorite for reelection, even though he may have overpromised the economic benefits of JCPOA, even though he is perhaps less a reformer than his supporters once hoped and even though his ability to manuever in a second term will likely be limited.

6. Canada: May 27

Conservative Party leadership election

As Liberal prime minister Justin Trudeau’s honeymoon continues well into his first term, the Conservative Party this spring will turn to selecting a permanent leader who can attempt to steer the Tories back to power after Stephen Harper’s loss in October 2015.![]()

The most notable aspect of the race is that so many leading figures have ruled out a leadership bid, including former defence minister Jason Kenney, former defense and justice minister Peter MacKay and popular three-term Saskatchewan premier Brad Wall. Notably, it will be the first time since 2004 that the Conservatives have chosen a leader and just the second time since the 2003 merger between the eastern-based Progressive Conservative Party and the western-based Canadian Alliance.

Kellie Leitch rose to the front tier of candidates after Trump’s victory with a hardline anti-immigration and ‘anti-elite’ message not dissimilar to Trump’s. Leitch, a 46-year-old MP from northern Ontario, served as labour minister in Harper’s final two years in office. Her ‘Trumpista’ message — including a plan to screen foreign visitors and residents alike for ‘anti-Canadian values’ — has boosted her poll numbers and her headlines, though it’s not clear that will garner her the majority she will need to win the leadership.

On the other edge of the party is Michael Chong, another Ontario MP who has served as minister of intergovernmental affairs. The 45-year-old Chong, whose father immigrated from China and whose mother immigrated from The Netherlands, projects a big-tent Conservative vision, with a liberal, center-right orientation that welcomes immigrants and that recognizes climate change as a crucial threat (he’s the only contender supporting a carbon tax). While Chong represents a compelling vision for the future of the Canadian right that would present a tough challenge to Trudeau, it may not turn out to be a vision Tory voters share in 2017.

Québec MP and former industry minister Maxime Bernier has cast himself as the libertarian choice to lead the Tories, with a conventional pro-market message tempered with a relatively socially liberal perspective. The 53-year-old Bernier is neck-and-neck with Leitch in fundraising, though he enjoys much more establishment support. His background as a French Canadian could put Québec, at long last, into play for the Tories. Just as Chong has attacked Leitch for taking xenophobic positions, Bernier has mocked Leitch as the ‘karaoke’ version of Trump. Though Bernier might not hold the same broad appeal to the Canadian electorate as Chong, he would still be a formidable challenger to Trudeau.

Given the 13-person field, with no candidate winning much more than 10% or 15% of the vote in early polls, it’s especially hard to forecast who could ultimately win nearly six months from now. In light of the runoff system, it’s entirely possible that none of Leitch, Chong or Bernier can win a majority and, instead, a ‘consensus’ candidate will emerge as acceptable to all factions. Most likely? Ontario MP Erin O’Toole, a former minister of veterans affairs; Ontario MP Lisa Raitt, former transport, labour and natural resources minister; or former House of Commons speaker Andrew Scheer, a Saskatchewan MP.

One wild card? Businessman Kevin O’Leary, who is increasingly nudging toward a run. If Leitch is running on the populist and anti-immigration ideas that fueled Trump, O’Leary would be running on the same celebrity and business outsider platform that boosted Trump as a candidate. The Montreal-born O’Leary often appears on the Apprentice-like Shark Tank, and he has a storied business career in the entertainment and software industries in Canada.

Bottom line: In contrast to Trudeau’s easy victory to become Liberal leader, the race to lead Canada’s Conservatives is still wide open. Keep an eye out for those candidates who can win an absolute majority with an appeal to both nationalist and globalizing wings of the party, appeal to both easterners and westerners and who can at least speak passable French.

7. Lebanon: likely May

parliamentary elections

The last time that Lebanon held elections in June 2009, the country’s jumble of religion-based confessional groups (Maronite Christians, Sunni Muslims, Shiite Muslims, Greek Orthodox, Druze, Armenian Orthodox, Armenian Catholic and many others) and individual-driven parties divided easily into two camps. ![]()

The February 2005 assassination of former prime minister Rafik Hariri brought decades of Syrian interference in Lebanese politics to a boiling point. The Assad family, through 2005, essentially held a veto on all political and policy matters in Lebanon. Hariri’s assassination, widely attributed to Syrian agents, changed that calculus, and so Lebanon’s politicians thereafter fell chiefly into the anti-Syrian ‘March 14 coalition’ or the pro-Syrian ‘March 8 coalition.’

Twelve years later, Lebanon has now watched Syria endure five years of civil war and absorbed 1.5 million refugees as a result of the conflict. Syrian president Bashar al-Assad couldn’t call the shots in Aleppo until recently, let alone in Beirut. If the Syrian civil war somewhat paralyzed Lebanon’s political institutions, it didn’t destroy them, and it’s to the credit of the Lebanese people that they’ve mostly prevented the Syrian conflict from re-igniting the divisions that caused a civil war in Lebanon in the 1980s.

That circumstance explains, in part, why after 30 months and 46 attempts, the old coalition lines fell and Lebanon’s parliament elected former civil war militia leader Michel Aoun as its president, paving the way for fresh legislative elections this year. Rafik’s son Saad Hariri returned as prime minister to lead a unity government through the next elections — and with the support of both the Shiite militia and political party Hezbollah and Aoun’s longtime Maronite rival, Samir Geagea, the leader of the Lebanese Forces party and militia. (By convention, Lebanon’s president is a Maronite, its prime minister a Sunni).

Elections for the 130 seats to the Lebanese parliament will not change, in any major way, the composition of the current parliament. Maronite seats will continue to be held by Maronites, Druze seats will continue to be held by Druze politicians (like Walid Jumblatt, the leader of the Druze-interest Progressive Socialist Party), and so forth.

But Aoun’s election shows that the March 8 / March 14 dividing lines are crumbing, and that demonstrates that the possibilities for Lebanon’s politicians to make progress in 2017 are much more optimistic than at any time since before the Syrian civil war began.

Bottom line: It’s true that Lebanese elections are highly choreographed affairs that divide on confessional lines. That the country has found a path to elect a president and hold elections as usual is a staggering statement of Lebanese durability and resolve in the face of the destabilizing forces of civil war in neighboring Syria.

8. Mexico (state): June 4

state gubernatorial election

Perhaps no country will feel more impact from Trump’s rise than Mexico, with his impolitic tirades against undocumented Mexican migrants and his call to build an improbable wall along the southern US border. That will only complicate an already crowded and murky Mexican presidential race in 2018.![]()

![]()

Among the handful of gubernatorial elections in Mexico this year, none will be more important than that of central Mexico state (‘Estado de México’ or simply ‘Edomex’), home to 16 million people, over 14% of the Mexican population nationwide.

Before his elevation to the presidency in 2012, Enrique Peña Nieto served as the governor of Mexico state and, indeed, it’s a state where the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party) has never wielded its grip on power. Eruviel Ávila easily won election in 2011 with over 64% of the vote after the PAN and the PRD failed in negotiations to field a joint coalition candidate.

But Peña Nieto and his party have become so unpopular that the PRI’s hold on Mexico’s most populous state could end this year. If it does, the PRI may not only be headed for a defeat in 2018, but an outright electoral disaster. On the other hand, a victory for the conservative Partido Acción Nacional (PAN, National Action Party), or for an an independent candidate or even one of Mexico’s two left-wing parties could likewise bolster their hopes for 2018.

Already deeply unpopular over violence and corruption, Peña Nieto faces a new crisis as protests flared across the country, including in Mexico state, over the controversial gasolizano, a 14% increase in the price of gasoline that took effect on January 1. In a country where drivers already pay more for fuel than their US counterparts, the price increases could sour voters on a package of energy sector reforms that opened the country’s nationalized oil and gas sector to limited private development.

Polls currently give the PRI a fragile generic lead in the state, with the PAN in second place, followed by the Movimiento Regeneración Nacional (MORENA) of former Mexico City mayor Andrés Manuel López Obrador and the Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD, Party of the Democratic Revolution) to which López Obrador once belonged.

Though the candidates for Mexico’s gubernatorial race aren’t yet settled, the most popular PAN candidate is its 2012 presidential nominee, Josefina Vázquez Mota. Though her political background lies in Mexico City (until last year, Mexico’s federal district), the city is almost completely surrounded by the state of Mexico, and much of the overflow population growth from Mexico City in recent years has been absorbed by Mexico state.

For now, the likeliest candidate for the PRI is Peña Nieto’s nephew, Alfredo del Mazo Maza, a federal deputy who has also served as the municipal president of Huixquilucan and as the director of the National Bank of Public Works and Services. His chief qualification, however, is his family’s political pedigree; his grandfather (in the 1940s) and father (in the 1980s) also served as state governor. Head-to-head polls shows that he would struggle to defeat Vázquez, with Delfina Gómez Álvarez, also a federal deputy from the state of Mexico, placing third under the MORENA banner. So don’t rule out the possibility that the PRI could choose another candidate, such as Ana Lilia Herrera, a Mexican senator, or Ernesto Nemer, the head of Mexico’s consumer protection agency.

Alejandro Encinas, the PRD’s 2011 gubernatorial candidate and a senator representing Mexico state, trails far behind. Since 2011, the López Obrador-led MORENA has sapped support from a generally driftless PRD at both the state and national level. The PRD is anxious to join forces with the PAN in state elections in 2017, as it did in gubernatorial elections last year in Durango, Quintana Roo and Veracruz.

Bottom line: If the PRI can’t win this state in 2017, it’s hard to see how it will retain the presidency (or much else) in 2018. A Vázquez victory would boost the PAN’s 2018 hopes, and the race will tell us much about the ongoing fight for leftist voters between the PRD and MORENA.

9. Venezuela: July through December

regional gubernatorial and municipal elections

possible presidential recall

No country suffered more in 2016 than Venezuela, and no country in 2017 seems more likely to suffer under the twin ills of inflation and economic contraction, even if oil prices continue to recover, in what has been a years-long death spiral for the socialist state. ![]()

Hugo Chávez’s death in 2013 left his successor, the far less capable Nicolás Maduro, with a series of problems that might have vexed even Chávez, with his considerable political gifts. Not surprisingly, Maduro is now deeply unpopular. Though 2017 could be the year that chavista rule ends, don’t be surprised if it continues to linger on — even without Maduro.

State elections were set to be held in December, but the chavista-controlled election council last October postponed those to sometime in mid-2017, given that last autumn, the Venezuelan bolívar was in the midst of a devastating devaluation crisis. But no one really knows for sure when those elections (and municipal elections scheduled for later in the year) might be held.

Opposition figures currently serve as governor in just two of the 10 largest states — 2013 presidential challenger Henrique Capriles in Miranda state and former chavista Henri Falcón in Lara state. With Maduro’s deep unpopularity, however, the governing Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela (PSUV, United Socialist Party of Venezuela) could lose many of those state races, including in Zulia state, where it won the governor’s office in 2012 for the first time — and only narrowly.

Since the 2015 parliamentary elections, the opposition coalition, the Mesa de la Unidad Democrática (MUD, Democratic Unity Roundtable), has controlled Venezuela’s legislative assembly. Nevertheless, 16 years of uninterrupted chavista rule has left much of the judiciary, the state oil company and other key government agencies firmly in the hands of the PSUV, therefore thwarting any opposition efforts to wrest power from Maduro. The opposition remains so powerless that Leopoldo López, a top opposition leader, remains imprisoned on political charges that stem from peaceful protests in 2014.

Nevertheless, the opposition collected enough signatures last year to force a recall election against Maduro. Last year, the election council also postponed any such recall until at least 2017. That means that a successful recall vote would not result in a new presidential election, but rather elevate Maduro’s vice president (currently, Aristóbulo Istúriz, a former state governor of Anzoátegui). As the PSUV looks to the next presidential election, however, and as international pressure rises on Venezuela to hold a recall, including from abroad (it was suspended from the Mercosur trading bloc in December), the ruling chavista class — and that includes many of the country’s military elites — would not necessarily be devastated to see Maduro’s fall.

Bottom line: The chavista grip on power seems unlikely to fade anytime soon, given the still-too-ineffective opposition. That’s despite widespread disenchantment with Maduro, who may be sacrificed on the path to the 2018 presidential election.

10. Rwanda: August 4

presidential election

There’s not a lot of suspense about Rwanda’s presidential election.![]()

Paul Kagame, who has held the presidency since 2000 and, informally, controlled Rwanda since the end of the civil war in 1994, will be reelected, barring a catastrophe after the country revised its constitution in 2015 to permit his reelection. Kagame, therefore, will almost certainly rule his country through 2024, and with genuine support from voters after restoring peace, tranquility and economic progress to his country. In both absolute terms and relative terms to neighbors like Congo and Burundi, Rwanda is thriving.

Kagame’s successes have come at some costs, however, including an increasing crackdown on political dissent and press freedom. Once the darling of the international community, Kagame has suffered some pushback for his increasing authoritarianism and misadventures stirring up trouble across central Africa. While Kagame is essentially as benevolent an authoritarian as exists in the world today, he’s done little to implement any kind of genuine democracy in Rwanda.

More ominously, Kagame has failed (so far, at least) to build the kind of institutions that could guarantee Rwanda’s success in a post-Kagame era. There’s a risk that if and when Kagame leaves office, the country may revert to its prior divisions, given that so much of Rwanda’s stability today depends on Kagame’s personality-driven vision.

Bottom line: Kagame’s all-but-assured victory provides little encouragement for neighboring authoritarians who refuse to leave office. Nevertheless, the key for Rwanda’s political development in the next seven years will be to institutionalize Kagame’s successful vision for peace and development.

11. Kenya: August 8

presidential and parliamentary elections

Kenya’s 2017 election is shaping up to be something of a rematch of the 2013 election. ![]()

Uhuru Kenyatta, elected in a far more peaceful process four years ago than under the violent conditions of the 2007 election, will seek reelection as the Kenyan economy continues to grow at a decent pace of around 6% in both 2016 and 2017 (as projected). Kenyatta will also run for a second term without the cloud of an international prosecution hanging over his head, after the International Criminal Court in 2014 dropped its case against Kenyatta for his role in inciting election-related violence in 2007 and 2008. Kenyatta’s Jubilee Coalition will be united, bringing together supporters within Kenyatta’s own Kikuyu ethnic group (Kenya’s largest) and the Kalenjin ethnic group of his deputy president, William Ruto, whose own ICC case was dropped in 2016.

Odinga, who comes from the smaller Luo ethnic group and who served as prime minister from 2008 to 2013 after the disputed victory of Mwai Kibaki, leads the Coalition for Reforms and Democracy (CORD). He will have to make the case that, despite one of east Africa’s fastest-growing economies, Kenyatta hasn’t done nearly enough to reduce unemployment and lift Kenyans out of poverty, especially for a country when the average age is just 19.5 years old and youth joblessness is rampant. Kenyatta’s administration has made some efforts to hold ministers accountable for graft, but corruption continues to plague the country.

Odinga might also chide Kenyatta for doing too little to keep Kenyans safe in the aftermath of high-profile attacks both in Nairobi and on the increasingly dangerous Somali coast, even while the government has often resorted to heavy-handed and authoritarian tactics in the name of fighting terrorism.

Throughout 2016, Odinga led protests against corruption within the Independent Electoral Boundaries Commission, and Odinga has argued that he was the legitimate winner of the last two elections (a credible assertion in 2007, far less so in 2013). Kenyatta’s government responded forcibly, foreshadowing the possibility of more electoral violence as the 2017 campaign approaches.

Odinga has a credible claim to the presidency but polling, for what it’s worth, shows that Odinga has an uphill climb. With so much of Kenyan politics drawn by ethnic lines, Odinga has not yet convincingly demonstrated that he can pull together an alliance of ethnic groups who, like the Luo, have been continually left out of national government. Voters will also vote simultaneously for both houses of its parliament — 337 members of the National Assembly and 67 members of the Senate.

Bottom line: Kenyatta has an edge for reelection, especially if Odinga fails to shake up the ethnic lines that drive Kenyan politics, though the bigger question will be whether the country can mark another peaceful election and restore its image as east Africa’s anchor of stability.

12. Germany: likely September

parliamentary elections

After Trump’s election in the United States, a handful of commentators plumped that it was Germany’s chancellor Angela Merkel who would now hold the claim as ‘leader of the free world.’![]()

That’s not particularly a title Merkel seems anxious to hold, however, as she attempts to win a rare fourth consecutive term as chancellor. Merkel must certainly remember the hubris of her mentor, Helmut Kohl; she was around when he tried to win a fifth consecutive term (and lost badly).

It’s true that Merkel’s popularity is lower today than it was when she nearly won an absolute majority in the 2013 federal elections for her Christlich Demokratische Union (CDU, Christian Democratic Union). Few voters in 2017 will give her credit for defusing a political and economic crisis with Greek prime minister Alexis Tsipras that nearly led to Greece’s expulsion from the eurozone, and few voters will give her credit for steeling the resolve of the remaining 27 EU member-states after the United Kingdom’s voters chose to exit the European Union in June 2016.

On a continent where French president François Hollande is universally despised, where European Commission president Jean-Claude Juncker is mocked as a soggy dilettante, where European Council president Donald Tusk is threatened by increasingly illiberal political opponents back home in Poland, where now-former Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi has lost his own electorate and where no future British prime minister will ever matter again, Merkel stands alone as the source of Europe’s power, grace and legitimacy.

As she looks to her own domestic challenge, however, little of that matters to her electorate.

Merkel rarely takes bold policy steps, but her decision to welcome nearly a million migrants to Germany in the summer of 2015 consumed much of Merkel’s considerable political capital. In some ways, that migrant crisis — the worst in Europe since World War II and fueled by instability in Iraq and Syria, but also by repressive governments or anarchic zones as diverse Afghanistan, Eritrea, Somalia and Libya — tipped off the clash-of-civilizations nationalism that fueled the rise of Trump and many of Europe’s far-right nationalists.

Merkel, too, isn’t immune from the pressure of anti-immigration sentiment. By calling last month for a ban on head scarves, she signaled that she is willing to take a harder line on refugee policy in the future. Nevertheless, the eurosceptic, anti-refugee Alternative für Deutschland (AfD, Alternative for Germany), a relatively new party founded in 2013, continues to build its support. Under the leadership of the cheery 41-year-old Frauke Petry, the AfD now holds seats in a majority of Germany’s 16 states, and it could win up to 15% of the national electorate later this year.

Despite all of that, Merkel’s CDU (and its more conservative Bavarian sister party) still holds a double-digit lead of anywhere from 10 to 18 percentage points in polling against the center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands (SPD, Social Democratic Party). What’s more, Merkel’s former junior coalition partners, the economically liberal Freie Demokratische Partei (FDP, Free Democratic Party), now under the leadership of Christian Lindner, consistently polls above 5%, the threshold to win seats the lower house of Germany’s parliament, the Bundestag.

The SPD has spent two of the last three governments as the CDU’s junior partner in a Große Koalition, a grand left-right coalition. In the past two elections, the Social Democrats nominated for chancellor two jowly, dour figures, both compromised after having served in high-level positions in Merkel’s governments — former foreign minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier in 2009 and former finance minister Peer Steinbrück in 2013. Both candidates led the Social Democrats to near-disastrous lows as they failed to draw sufficient contrasts with Merkel’s vision for Germany.

In 2017, the SPD seems content to make the same mistake. Despite the return of European Parliament president Martin Schulz to national politics, the party seems set to nominate for chancellor Sigmar Gabriel, Merkel’s vice chancellor and economy minister and yet another fleshy apparatchik of the left. Even as Russian president Vladimir Putin has signaled his ability to deploy ‘cyber’ dirty tricks to help defeat Merkel, who has taken an aggressively anti-Russian line following the annexation of Crimea and ongoing Russian malfeasance in eastern Ukraine, it is difficult to imagine the resurgence of the Social Democrats in 2017.

Though Gabriel seems destined to lead the SPD to another loss, there’s nevertheless still a moderate chance that he could form a majority through an untested (at least at the national level) ‘red-red-green’ coalition. That would join the SPD in government with the hard-left Die Linke (Left Party), which includes remnants of the old East German communists, and Die Grünen (the Greens), the SPD’s most reliable coalition partner. The SPD governs in a red-red-green coalition in Berlin today, and the Left since 2014 has led a similar coalition in Thuringia under minister-president Bodo Ramelow. But it remains a controversial step for the SPD at the national level.

It’s likely that Merkel, if she wins this autumn, will pursue a coalition with the Greens herself, a party that increasingly appeal to affluent voters. The archetype is Winfried Kretschmann, the popular Green minister-president of the wealthy southwestern state of Baden-Württemberg. Merkel’s post-Fukushima decision to halt nuclear energy in 2011 accomplished one of the top goals of the Greens and eliminated one of the most drastic obstacles to a ‘black-green’ coalition, and the two parties conducted serious coalition negotiations in 2013. Another possibility, with the likely return of the Free Democrats to the Bundestag, is a so-called ‘Jamaica’ coalition (so named after the Jamaican flag, given the ‘yellow’ banner of the FDP).

If she wins, Merkel must certainly realize that a fifth term isn’t likely in the cards. Her priorities must be to cultivate one or more potential successors, continue to integrate the deluge of refugees within German society, stabilize a post-Brexit European Union and perpetuate the brand of transatlantic and internationalist neoliberalism that Germany now represents more than either the United States or the United Kingdom.

Bottom line: Boring is as boring does. For now, Angela Merkel remains a favorite to win reelection to a fourth term as Germany’s chancellor — at least so long as the Social Democrats fail to show any political imagination. The more important question is the level of support that the Alternative for Germany will command. One tantalizing possibility? The long-awaited coalition between Merkel’s Christian Democrats and the Greens.

13. China: likely autumn

19th National Congress of the Communist Party of China

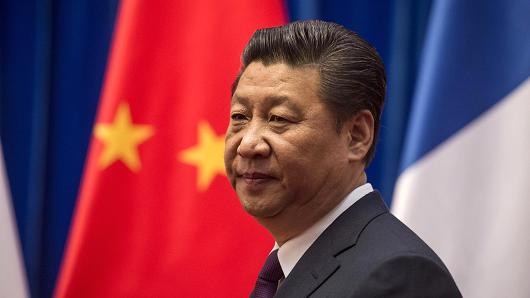

It’s not an election, but it’s still the most important political event of the year in the world’s most populous country.![]()

Every five years, the Chinese Communist Party (中国共产党) gathers to hold its national congress, and this year will be the 19th such congress in the history of the People’s Republic of China.

Xi Jinping (习近平), China’s paramount leader and president, has amassed more power than either of his two most immediate predecessors, Jiang Zemin (江泽民) and Hu Jintao (胡锦涛). A high-profile anti-corruption campaign has demonstrated Xi’s willingness to challenge both the Party grassroots and the party elite, including former Chongqing party leader Bo Xilai (薄熙来) and Zhou Yongkang (周永康), a retired member of the all-powerful Politburo Standing Committee. Critics have credibly challenged that the anti-corruption efforts, however, are also aimed at purging Xi’s critics from positions of power.

Committed to a gentle landing for a Chinese economy that’s notching lower GDP growth rates in the 2010s, Xi is setting the pace for international efforts to reduce greenhouse gases (even as Trump threatens to pull out of the Paris agreement on climate change that Xi’s regime successfully negotiated with the Obama administration). Even as the Chinese economy continues to liberalize, and as his government has been willing to phase out old relics like the one-child policy, Xi has cracked down on Internet freedom and other political liberties (even in Hong Kong) that had gradually, if only slightly, liberalized in past years.

Xi has also projected a far more muscular image of China’s role in the world, both in terms of flexing Chinese military might in the South China Sea and demonstrating China’s economic might in the Asia-Pacific region and beyond to the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. Under Xi’s leadership, China has created the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and is quickly developing the alternative trade framework to the flailing US-led Trans-Pacific Partnership. Indeed, when Trump takes office in Washington, D.C. on January 20, Xi will travel to the World Economic Forum in Davos a day later to cast a defense of globalization — at least, globalization with Chinese characteristics. The American president-elect has already clashed with China by taking a congratulatory phone call from Taiwan’s newly elected and nominally pro-independence leader, Tsai Ing-wen (蔡英文). China will likely spend much of 2017 teasing out just how far Trump is willing to antagonize Beijing (or, alternatively, make deals).

All of this will inform the most important decisions of the 19th National Congress — the Party’s policy positions for the next five years and the composition of the new Politburo Standing Committee, along with the 25-member Politburo, the wider 205-member Central Committee and countless other civilian and military positions that will influence who rises in the next generation of Chinese leadership.

Xi and China’s premier Li Keqiang (李克强) are likely to remain, but the remaining five members are all above the retirement age (68), so many observers believe that at least new five members will join the Standing Committee. The committee, which was reduced in number from nine to just seven at the 18th National Congress in 2012, might also expand back to eight or nine this year. There’s a chance, also, that Xi will retain the 68-year-old Wang Qishan (王岐山), who serves as the secretary of the central commission for discipline inspection and, therefore, has led Xi’s anti-corruption campaign.

Much speculation focuses on two up-and-coming stars of the so-called ‘sixth generation’ set to take the reins from Xi in 2022 (if Xi follows the most recent convention of his predecessors).

Sun Zhengcai (孙政才) has served as party secretary of Chongqing since November 2012, taking over shortly after Xi rival Bo Xilai’s downfall. At just 53 years old, Sun has already served as China’s minister of agriculture and as Party secretary of Jilin province. Unlike Xi, who is the son of a leading Party figure, Sun comes from a family of farmers.

Hu Chunhua (胡春华), also 53 years old, has served as Party secretary of Guangdong province, the southern economic powerhouse, since December 2012 after a long career in Tibet and Inner Mongolia and is very much a protege of Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao.

Other spots on the Politburo Standing Committee could go to the 61-year-old Wang Yang (汪洋), a leading contender to join the committee in 2012 and himself a former Party secretary in both Chongqing and Guangdong. Wang, a gregarious official in public, currently serves as one of China’s four vice-premiers. Like Xi, Wang is known as an economic reformer; unlike Xi, Wang has also favored political liberalization. Li Zhanshu (栗战书), the 66-year-old director of the Party’s general office, and a former Party secretary in Guizhou and Xi’an, is also widely speculated for a seat on the Standing Committee.

Bottom line: It’s very much Xi’s Party, and speculation is just that — speculation. China will spend a lot of the year trying to understand exactly how to navigate the Trump-led United States. We’ll learn a lot, however, about China’s future from the composition of the new Politburo Standing Committee.

14. Honduras: November 26

presidential and parliamentary elections

When former president Manuel ‘Mel’ Zelaya contemplated just the notion of running for reelection, it was enough to engender a legislative and military coup that ousted the Honduran leader from office eight years ago.![]()

In 2017, following a controversial decision last year by Honduras’s supreme court, Juan Orlando Hernández, who rose to power in 2013 as the law-and-order candidate of the Partido Nacional (PN, National Party), will be permitted to run for reelection. Though Hernández will indeed seek a second term, polls throughout 2016 show that he remains (for now) a favorite to win, despite lingering evidence that his party is engaged in corruption.

The opposition continues to split between the traditionally centrist Partido Liberal (PL, Liberal Party) and the more leftist breakway Libertad y Refundación (LIBRE, Liberty and Refoundation). Both parties will hold primaries on March 12 to determine their candidates. Leading Liberal contenders include Luis Zelaya, a former president of the Central America Technologic University and Enrique Ortez, a former magistrate who controversially served as the foreign minister in Roberto Micheletti’s interim (post-Zelaya) government in 2009.

On the Libre side, Xiomara Castro de Zelaya (the wife of the former president) hopes to lead her party again in 2017 after losing to Hernández in 2013 by just eight points, though she faces challenges from activists Rasel Tomé and Jari Dixon.

Since the 2009 coup and the rise of the National Party later that year, labor, indigenous LGBT and other activists have been killed, and previously independent institutions, like the judiciary, have increasingly acted more like organs of the National Party’s government.

Voters will simultaneously elect all 128 members of the National Congress.

Bottom line: Though Hondurans believe Hernández is corrupt and his bid for a second term amounts to a hypocritical power grab, he will likely win a joyless reelection unless the opposition can unite forces behind a charismatic challenger.

15. Thailand: likely November

parliamentary elections

Generally, your expectations for Thailand’s scheduled elections in late 2017 should not be too high. Even in the new year, there are signs that elections could be pushed to 2018.![]()

Even if the vote goes forward as announced by Thailand’s ruling military junta, it will take place under a new constitutional regime that gives the Thai military incredible powers going forward in Thai policy matters. After voters approved the changes in a referendum last August, the Thai military will essentially be in a position to approve any future government, prime minister, the bureaucracy and the judiciary.

In the last elections in 2011, Yingluck Shinawatra easily won on a populist campaign built on the platform that her brother, Thaksin Shinawatra, used to win power in 2000s (before being forced out of office and into exile) by appealing to rural farmers and the poor in northern Thailand. Meanwhile, the political opposition based in Thailand’s south and within the small Bangkok-based middle class and elite, has been unable to unlock a broad-based electoral victory in nearly two decades.

The Shinawatra family often attempted to divert more resources to Thailand’s poor, including an ill-fated rice subsidy scheme that backfired disastrously. The military ousted Yingluck in 2014, and she is currently in the midst of a criminal trial over the rice subsidy’s failures. Moreover, it’s unsure, given the hard line that Prayuth Chan-Ocha, the military junta leader, took in the lead-up to the 2016 referendum, whether any election campaign will take place with any semblance of free speech or assembly. Predecessors to Yingluck’s Pheu Thai Party (PTP, พรรคเพื่อไทย) have been disbanded by authorities before and may so again.

Bottom line: Don’t be surprised if the Thai elections are postponed well into 2018. The ongoing trial of Yingluck Shinawatra could dent her popularity, but if she nevertheless wins the next elections, it will force a confrontation with a military deep state that has now developed permanent roots in Thai politics.

16. South Korea: December 20 (or earlier)

presidential election

As Ban Ki-Moon (반기문) planned to step down on December 31 after a decade as the secretary-general of the United Nations, he must have thought he would have the luxury to spend most of 2017 preparing what was likely to be a campaign for South Korea’s presidency.![]()

Instead, South Koreans may be electing a new president far sooner.

That’s because the incumbent, Park Geun-hye (박근혜), is in the midst of an impeachment trial by the Constitutional Court for accepting illicit funds in one of the quirkiest scandals to emerge in 2016 — or any other year. Late last year, Park was revealed to have governed in thrall to Choi Soon-sil, a longtime friend and the daughter of a Korean Christian cult leader. You really can’t make up some of the outrageous details, and they paint the picture of a president defrauded by her friend, but isolated both in her time in the Blue House and going back all the way to the days when she essentially filled the first lady role for her father, Park Chung-hee (박정희), who served as president from 1961 until his assassination in 1979.

Already unpopular after the sinking of the Sewol ferry in April 2014 that killed 295 Koreans, Park has faced criticism for governing in an authoritarian manner reminiscent of her father’s rule, with a harder line against press freedom than recent administrations. Indeed, the Constitutional Court is weighing, in addition to bribery charges, whether Park committed dereliction of duty during the Sewol incident.

Six of the nine judges on the Constitutional Court are required to remove Park from office, and they will have until possibly May 2017 to deliberate. Six judges were appointed by Park or are otherwise friendly to Park’s conservative Saenuri Party (새누리당, ‘New Frontier’ Party), but two of the judges’ terms will end before May 2017, so the outcome very much is uncertain.

If Park is removed, South Korea will hold a new presidential election within 60 days.

Saenuri is already showing signs of crumbling, with a breakaway ‘conservative reform’ faction that has condemned Park, voting to recommend impeachment last November. It’s hardly the ideal platform for Ban, who hoped he could return to Seoul as an elder statesman and ride the Saenuri ticket to an easy victory.

The center-left opposition Minjoo Party (더불어민주당), a successor to what used to be called the Democratic United Party, leads nearly all of the polls, and it performed surprisingly well in the April 2016 legislative elections, when it won one more seat than the Saenuri in the 200-member national assembly, depriving Park and Saeunri of its legislative majority.

The Minjoo Party will hold a primary to choose its nominee. For now, the most popular choice is the party’s 2012 nominee, the 63-year-old Moon Jae-in (문재인), a former chief of staff to former president Roh Moo-hyun (노무현) in the mid-2000s. (Notably, while Ban is now closer to the Korean conservatives, he previously served as Roh’s foreign minister from 2004 until taking up his UN post).

Meanwhile, all of the buzz is with 52-year-old Lee Jae-myung (이재명), who has emerged as a kind of ‘Bernie Sanders’-style figure of the Korean left. As mayor of Seongnam, he has introduced social welfare reforms designed to boost youth employment and education and to reduce poverty of the elderly. Lee’s candidacy is especially appealing to those voters who are tired of fighting over Roh’s controversial presidency and simply want to move on. Seoul’s mayor since 2011, Park Won-soon (박원순), a critic of the president and a longtime human rights activist, might also run for the nomination.

Ahn Cheol-soo (안철수), a software engineer and graduate school dean at Seoul National University, will also be in the mix as the leader of the newly formed People’s Party (국민의당). A popular figure who shook up the Korean political establishment with his 2012 presidential bid, he dropped out shortly before the election and endorsed Moon Jae-in. In 2017, his star has faded somewhat after the new party was implicated in a kickback scandal last summer.

Aside from the ongoing scandal and economic issues, South Korean voters may also have security on their minds in 2017 as well, with Trump suggesting that US allies in east Asia and with North Korea now threatening to test an intercontinental ballistic missile, raising fears of a nuclear attack on the Korean peninsula.

Bottom line: If Park Geun-hye is impeached sooner rather than later, it’s good news for the Korean left. If not, infighting between the Lee and Moon camps or between the Minjoo candidate and Ahn could clear a path for former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon’s next act in world politics. More than most world elections, this one could be reshaped by global actors or crises.

17. Italy: TBD

possible parliamentary elections

Italy may not go to the polls next year at all; officially, the next election must be held only before May 2018.![]()

But if the country’s politicians can find a way to salvage, scrap or reinterpret Italy’s electoral laws before the end of 2017, there’s a strong chance that Italian president Sergio Mattarella and Paolo Gentiloni, widely seen as a caretaker prime minister, will go to the polls sometime this year instead. Incredibly, for the first time since the 2008 election, Italy could have a prime minister with a credible claim to having won a mandate of the Italian electorate.

After Silvio Berlusconi’s ouster during the 2011 sovereign debt crisis, European officials virtually demanded the appointment of the technocratic Mario Monti as his successor. After labor-friendly Pier Luigi Bersani led the center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party) to a narrow victory in the 2013 election, coalition negotiations sidelined him in favor of party functionary Enrico Letta. In February 2014, Florence mayor and newly christened PD leader Matteo Renzi organized a friendly coup, taking the premiership for himself with rosy hopes of disrupting Italy’s cozy political elite and implementing widespread reforms.

Renzi, however, resigned in December 2016 after voters widely rejected a referendum on constitutional reforms designed to reduce the importance of the Italian senate. It follows a nearly three-year tenure with little to show, beyond the recognition of same-sex unions and a moderate labor market reform.

While the 41-year-old Renzi left for Florence to lick his wounds and regroup, Gentiloni will have to deal with a half-completed reform of the Italian election process and an ongoing banking crisis that could require his government to provide highly unpopular bailouts (or, in EU jargon, ‘precautionary recapitalisations‘).

If elections are called in 2017, Renzi will still likely lead the center-left Democrats, essentially tied in the polls with the anti-austerity and eurosceptic Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) founded in 2009 by comedian Beppe Grillo. In recent years, the Five Stars have made gains in local elections, including in Rome, where attorney Virginia Raggi was elected last summer as mayor. Though Raggi’s approval is already plummeting, and Grillo’s profile doesn’t strike many Italians as sufficiently serious for the premiership, Luigi Di Maio, a 30-year-old Napolitano with a moderate streak has become the Movement’s rising star and presumptive prime minister if the Five Stars wins the next elections.

Under both the old and new elections laws (the latter under review by Italy’s constitutional court), the party with the most votes will be assured a majority in the lower house, the Camera dei Deputati (Chamber of Deputies). That’s not true in the upper house, the Senato (Senate), which is elected on a regional basis and not via proportional representation like the lower house. Renzi’s referendum push hoped to reduce the Senate’s numbers from 315 to 100 and to reduce greatly its powers. Its failure means that any electoral system will have to grapple with the truly bicameral nature of Italy’s parliament.

With the Five Star Movement and the center-left so evenly balanced, the kingmakers may be an increasingly fragmented set of traditional center-right parties, including Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and an increasingly illiberal, nationalist, eurosceptic and anti-immigrant Lega Nord (Northern League). Once Berlusconi’s junior partners, the Northern League now routinely polls higher support than Forza Italia under its new leader Matteo Salvini.

Though Americans and Europeans alike share white-knuckled angst over the possibility of a Le Pen presidency in France or a Wilders premiership in The Netherlands, the risk of a hard-right government is arguably far greater in Italy.

The country’s GDP growth in 2016 was just 0.9%. That’s much better than in recent years, but it’s incredible that GDP growth hasn’t exceeded 2% since the year 2000. Unemployment hovers stubbornly above 11%, and youth unemployment is around 37%. With economic and employment conditions so poor and the euro (if not the notion of European union) so unpopular, it’s not a leap to imagine that that voters could turn to both the Five Stars and the Northern League in record numbers, giving western Europe — and a founding EU member, at that — the possibility of its first fully far-right government since the 1930s.

Bottom line: The risks that voters elect a far-right government are higher in Italy than anywhere else in Europe in 2017, though it’s possible that Italians will not even vote until 2018. Both Matteo Renzi’s ability to mount a comeback from his December 2016 referendum loss and the ability of Silvio Berlusconi to rally the center-right remain highly unclear. Despite stubborn support for the Five Star Movement, Italian voters may hold lingering doubts about its ability to perform in government, based on the Roman municipal experiment.

Notable Mentions

Though they didn’t make the ’17 to watch in 2017′ list, the following ten elections are still worth watching as the year in global politics unfolds:

- Jakarta gubernatorial election (February 15). Even if

president Joko Widodo hadn’t used his stint as Jakarta’s governor as a stepping stone to Indonesia’s presidency, this race would be important. A city of around 10 million, Jakarta presents some of the world’s most vexing issues of urban design and development. Widodo’s former deputy governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a Christian governor of Chinese descent and popularly known by his nickname Ahok, is vying for his first full term. He will face two high-profile opponents, and the race is likely to go to a second-round runoff. The first is Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, the candidate of the Partai Demokrat (Democratic Party) and son of Widodo’s predecessor as president. The second is Anies Rasyid Baswedan, an academic, university president and Widodo’s former education and culture minister, who will run as the candidate of the nationalist Gerindra (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, the Great Indonesia Movement Party).

president Joko Widodo hadn’t used his stint as Jakarta’s governor as a stepping stone to Indonesia’s presidency, this race would be important. A city of around 10 million, Jakarta presents some of the world’s most vexing issues of urban design and development. Widodo’s former deputy governor, Basuki Tjahaja Purnama, a Christian governor of Chinese descent and popularly known by his nickname Ahok, is vying for his first full term. He will face two high-profile opponents, and the race is likely to go to a second-round runoff. The first is Agus Harimurti Yudhoyono, the candidate of the Partai Demokrat (Democratic Party) and son of Widodo’s predecessor as president. The second is Anies Rasyid Baswedan, an academic, university president and Widodo’s former education and culture minister, who will run as the candidate of the nationalist Gerindra (Partai Gerakan Indonesia Raya, the Great Indonesia Movement Party).

- Ecuador presidential election (February 19).

Rafael Correa is not eligible for reelection, which means that the South American country — and one of the last bastions of the populist left in Latin America — will have a new president for the first time in a decade. If no candidate can both win more than 40% and lead the second-placed candidate by more than 10%, the contest will proceed to a runoff. Lenín Moreno, a former vice president under Correa from 2007 to 2013 and a paraplegic who has worked to improve conditions for Ecuador’s disabled, will represent Correa’s left-wing Alianza País coalition, and Moreno is heavily favored to win against Guillermo Lasso, a businessman who lost to Correa by a nearly three-to-one margin in 2013. Ecuador will simultaneously elect 137 members of its national assembly.

Rafael Correa is not eligible for reelection, which means that the South American country — and one of the last bastions of the populist left in Latin America — will have a new president for the first time in a decade. If no candidate can both win more than 40% and lead the second-placed candidate by more than 10%, the contest will proceed to a runoff. Lenín Moreno, a former vice president under Correa from 2007 to 2013 and a paraplegic who has worked to improve conditions for Ecuador’s disabled, will represent Correa’s left-wing Alianza País coalition, and Moreno is heavily favored to win against Guillermo Lasso, a businessman who lost to Correa by a nearly three-to-one margin in 2013. Ecuador will simultaneously elect 137 members of its national assembly.

- Timor-Leste presidential and parliamentary elections

(April / June). The 2017 parliamentary elections will be the first time that Xanana Gusmão, independence hero, former president and prime minister of Timor Leste (or East Timor) will not be running or holding the office of president or prime minister, though he continues to play an official role in government as planning and strategic development minister and an unofficial behind-the-scenes role in his country’s political life. Taur Matan Ruak, a former guerrilla, is standing for reelection as president.

(April / June). The 2017 parliamentary elections will be the first time that Xanana Gusmão, independence hero, former president and prime minister of Timor Leste (or East Timor) will not be running or holding the office of president or prime minister, though he continues to play an official role in government as planning and strategic development minister and an unofficial behind-the-scenes role in his country’s political life. Taur Matan Ruak, a former guerrilla, is standing for reelection as president.

- Turkey referendum on presidential system (April).

It’s no secret that Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan hopes to transform his country from a parliamentary to a presidential system, even before his successful transition from prime minister to president in the country’s first-ever direct presidential election in 2014. Two general elections in 2015 were framed as an opportunity to deliver to Erdoğan the majority to do so, though the ruling Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, Justice and Development Party) failed in the first such vote to win a majority. A year later, after several terror attacks and a botched coup attempt, Erdoğan has cracked down on enemies both real (radical Islamists and Kurdish guerrillas) and imagined (Gulenists — the followers of US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen and one-time AKP allies — and Kurdish democrats). With so much chaos, Erdoğan clearly believes the time is right to go to voters to seek more explicit presidential powers, which could further envelop his grip on power and endanger Turkey’s fast-eroding democratic institutions.

It’s no secret that Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan hopes to transform his country from a parliamentary to a presidential system, even before his successful transition from prime minister to president in the country’s first-ever direct presidential election in 2014. Two general elections in 2015 were framed as an opportunity to deliver to Erdoğan the majority to do so, though the ruling Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, Justice and Development Party) failed in the first such vote to win a majority. A year later, after several terror attacks and a botched coup attempt, Erdoğan has cracked down on enemies both real (radical Islamists and Kurdish guerrillas) and imagined (Gulenists — the followers of US-based cleric Fethullah Gülen and one-time AKP allies — and Kurdish democrats). With so much chaos, Erdoğan clearly believes the time is right to go to voters to seek more explicit presidential powers, which could further envelop his grip on power and endanger Turkey’s fast-eroding democratic institutions.

- British Columbia provincial elections (May 9).

After Adrian Dix and the BC New Democrats botched a double-digit lead in 2013, premier Christy Clark is hoping that she can pull out yet another victory in 2017. Though Alberta elected an NDP premier in Rachel Notley just two years ago, ending a four-decade Tory hold on Alberta’s government, Notley and her policies have become increasingly unpopular as Canada suffers economically from low energy and commodities prices. Torn between environmental concerns and economic malaise, British Columbia voters in 2013 turned at the last minute toward economics over climate — and that was at a time when energy prices were much stronger and the Canadian economy was growing at a faster pace. Polls today show that Clark’s Liberals and the NDP, now under the leadership of John Horgan, are virtually tied. One odd quirk? Horgan and the BC NDP oppose the Trans Mountain pipeline extension, putting the party at odds with both Clark’s BC Liberals and Notley’s Alberta NDP.

After Adrian Dix and the BC New Democrats botched a double-digit lead in 2013, premier Christy Clark is hoping that she can pull out yet another victory in 2017. Though Alberta elected an NDP premier in Rachel Notley just two years ago, ending a four-decade Tory hold on Alberta’s government, Notley and her policies have become increasingly unpopular as Canada suffers economically from low energy and commodities prices. Torn between environmental concerns and economic malaise, British Columbia voters in 2013 turned at the last minute toward economics over climate — and that was at a time when energy prices were much stronger and the Canadian economy was growing at a faster pace. Polls today show that Clark’s Liberals and the NDP, now under the leadership of John Horgan, are virtually tied. One odd quirk? Horgan and the BC NDP oppose the Trans Mountain pipeline extension, putting the party at odds with both Clark’s BC Liberals and Notley’s Alberta NDP.

- North-Rhine Westphalia state elections (May 14). For

many German leftists, the perfect candidate of the future is Hannelore Kraft, the minister-president of Germany’s most populous state. The first woman to govern her state since taking office in 2010 at the head of a ‘red-green’ coalition between her Social Democratic Party and the Greens, Kraft has been a full-throated opponent of austerity measures in Germany. Polls leading to the May elections, however, show that the SPD is locked in a tough battle for first place with the Christian Democratic Union. While the states’s voters say they far prefer Kraft to the CDU’s Armin Laschet, the key question is whether Kraft and her allies will together win a majority and the level of support that the anti-immigration AfD attracts.

many German leftists, the perfect candidate of the future is Hannelore Kraft, the minister-president of Germany’s most populous state. The first woman to govern her state since taking office in 2010 at the head of a ‘red-green’ coalition between her Social Democratic Party and the Greens, Kraft has been a full-throated opponent of austerity measures in Germany. Polls leading to the May elections, however, show that the SPD is locked in a tough battle for first place with the Christian Democratic Union. While the states’s voters say they far prefer Kraft to the CDU’s Armin Laschet, the key question is whether Kraft and her allies will together win a majority and the level of support that the anti-immigration AfD attracts.

- The Bahamas parliamentary elections (May).

It’s a quiet year for elections in Caribbean democracies, but in The Bahamas, home to over 375,000 people, voters could elect just the fourth prime minister since the island nation won its independence in 1973. Since 1992, power has swung between the nominally conservative Free National Movement (FNM) and prime minister Hubert Ingraham and the nominally leftist Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) and prime minister Perry Christie. Since 2002, voters have rejected the incumbent party at each five-year interval. If they do the same in 2017 and vote Christie out of office, Bahamians will have elected the FNM’s Huber Minnis, who has served as opposition leader since 2012. Like many tourism-dependent Caribbean countries, the Bahamas has a high public debt-to-GDP ratio (around 80%), and crime continues to be a major issue for voters, who will elect all 40 members of the House of Assembly. As an offshore banking center with deposits of 26 times the country’s GDP, Bahamian officials have slow-rolled reforms for greater transparency following last year’s ‘Panama Papers’ scandal.

It’s a quiet year for elections in Caribbean democracies, but in The Bahamas, home to over 375,000 people, voters could elect just the fourth prime minister since the island nation won its independence in 1973. Since 1992, power has swung between the nominally conservative Free National Movement (FNM) and prime minister Hubert Ingraham and the nominally leftist Progressive Liberal Party (PLP) and prime minister Perry Christie. Since 2002, voters have rejected the incumbent party at each five-year interval. If they do the same in 2017 and vote Christie out of office, Bahamians will have elected the FNM’s Huber Minnis, who has served as opposition leader since 2012. Like many tourism-dependent Caribbean countries, the Bahamas has a high public debt-to-GDP ratio (around 80%), and crime continues to be a major issue for voters, who will elect all 40 members of the House of Assembly. As an offshore banking center with deposits of 26 times the country’s GDP, Bahamian officials have slow-rolled reforms for greater transparency following last year’s ‘Panama Papers’ scandal.

- Liberia presidential and parliamentary elections (October 10).