Five days after its July 2 election, Australians woke up Thursday morning to find that they still don’t know who will lead the next government — and that Standard and Poor’s is moving its ‘AAA’ credit outlook from stable to negative as political uncertainty reigns. ![]()

The only clear result of the first ‘double dissolution’ election since 1987 is that it might be days or weeks before Australians know who will hold a majority in either house of their parliament, with every possibility that both houses could wind up with no clear majority.

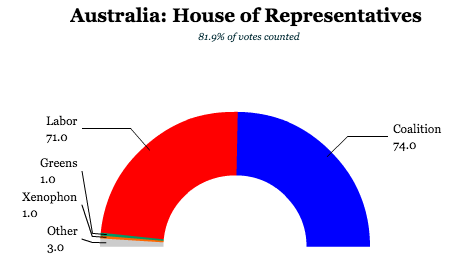

The other clear result is that the election is that, though his Liberal/National Coalition is growing closer to winning the narrowest of majorities, prime minister Malcolm Turnbull is the clear loser of the election. Just nine months into his premiership after he convinced his party to oust its prior (more conservative) leader Tony Abbott, Turnbull has lost at least 16 seats in the 150-member House of Representatives to the center-left Australian Labor Party (ALP). The Coalition, as things currently stand, is now trailing in the so-called two-party preferred vote (under Australia’s single transferable vote system) by the narrowest of margins — 50.09% for Labor to 49.91% for the Coalition.

For someone whose leadership pitch came down to electability, it means his days as prime minister might be numbered — even if the Coalition emerges with a majority.

Politics isn’t always fair, but Turnbull’s problem has always been that he’s a moderate in a conservative party.

I have no doubt that Turnbull, who has always been far more socially progressive than many other Coalition MPs, would like to accomplish some heady goals as prime minister. He’s been an ambitious man his whole life, and there’s no reason to believe that, with the right kind of mandate, Turnbull would like to solve several conundrums that neither the Coalition nor the Australian Labor Party (ALP) have been able to solve.

He might *like* to find a way to end the detention centers in Nauru and Manus Island without encouraging thousands of poor Asians to risk their live by getting on rafts to Australia, especially after Papua New Guinea’s supreme court ruled the Manus Island detention center unconstitutional.

He might *like* to have Australia’s parliament vote to pass marriage equality for gay and lesbian Australians and be done with an issue that now separates Australia from much of the rest of the developed world — almost all of western Europe, Canada, New Zealand and the United States.

He might *like* to redesign the failed carbon trading scheme that former Labor prime minister Julia Gillard enacted (and that Abbott, a few years later, abolished) as perhaps a business-friendlier carbon tax. After all, Turnbull lost his position as leader of the Liberal Party to Abbott in 2009 after he tried to compromise with the Labor government on climate change.

He might even *like* to take another run at an Australian republic after leading the pro-republic campaign in the failed 1993 referendum.

Of course, very few MPs and senators in the Liberal Party want any of those things, and their more conservative junior partners in the National Party would, if given the chance, turf out Turnbull tomorrow in favor of restoring Abbott (or, say, even Turnbull’s treasurer Scott Morrison).

Liberals went along with Turnbull’s coup to oust Abbott last September only because polls showed Abbott leading the Coalition to a horrific disaster in the next election. So Turnbull became prime minister on condition that, first, he wouldn’t pull the Coalition too far to the middle (in other words, putting a more moderate face on a government still more closely situated with Abbott on policy than Turnbull) and, second, he could continue to keep the Coalition on top in the polls against Labor’s Bill Shorten.

So that left Turnbull waging a reelection campaign on a fairly uninspired policy platform — a handful of reforms and a corporate tax cut to goose the economy. But Turnbull also needed a personal electoral mandate to accomplish any real legacy-building goals, though he couldn’t directly run on any ambitious policy goals without losing support from the right flank of his party.

While it looks like Turnbull will have won a very slim victory, it’s, in some ways, the worst result possible for Turnbull and for Australia.

Turnbull now has nothing in the way of a personal mandate, because he has disproved the notion that he wields the kind of electoral magic that won him the leadership just nine months ago. So if he goes on to lead a narrow majority government, Turnbull will now have an even harder time controlling his party and preventing a future counter-coup by Abbott or anyone else. Presumably, too, Turnbull will shelve plans, if they ever existed, of a more moderate or progressive Coalition agenda for the foreseeable future.

Shorten, of course, is very happy that Australia now sees in Labor’s leader a future prime minister after years of doubt. For the last three years, Shorten has mostly been able to unify a once highly-fractured Labor Party and present a thoughtful and coherent opposition to the Abbott/Turnbull government. But doubts about his union background and his relative lack of charisma pegged him as a lightweight, coming after the far more personable Rudd and the history-making Gillard.

By achieving so many gains in the 2016 election (now 16 seats in the House of Representatives and counting), Shorten has inoculated himself from his own leadership challenge. Under new rules implemented in the wake of Labor’s 2013 defeat — designed to reduce the regicidal tendencies that destabilized the Rudd government, then the Gillard government, then (again) the Rudd government — leadership spills now include a vote both by sitting MPs and by the party’s membership at large.

Former deputy prime minister Anthony Albanese, who served from 2007 to 2013 as minister of infrastructure and transport, still hopes, as a champion of the Labor left, still hopes for another chance at the leadership. Albanese only narrowly lost the 2013 leadership contest to Shorten, and Albanese won by a nearly 20% margin among the wider Labor membership. Had Labor made fewer gains, a challenge to Shorten might have been likely — and it still might if Shorten’s popularity doesn’t rise before the next election (which now certainly seems like it will come far before the end of three years).

In the full Senate, where results might not be known until August, while the hard-right Pauline Hanson has appalled Australians with an apparent victory from her hard-line, populist One Nation party, an entire constellation of small parties and independents could hold the balance of power.

Though the Australian Greens will be unhappy that they will only hold one seat in the House of Representatives, they will be pleased with a 1.2% swing in the popular vote to 9.8% and they could hold up to nine seats in the Senate.

Nick Xenophon’s ‘team’ is set to win a seat or two in the House and perhaps three senatorial seats, including Xenophon’s from South Australia. Though Xenophon started his career on the single issue of poker machines, he’s become a force for centrism and could well become the kingmaker in the next parliament if the Coalition falls just short of a majority.

For now, though, Australia seems headed for short-term political instability and medium-term policy paralysis.