It’s as if an entire season of Game of Thrones swept through British politics in the space of two-and-a-half weeks.![]()

The list of political careers in ruins runs long and deep. Prime minister David Cameron himself. Chancellor George Osborne. Former London mayor Boris Johnson. Justice secretary Michael Gove. Nigel Farage, the retiring leader of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP). Maybe even Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn, who may enjoy the support of grassroots Labour members, but not of his parliamentary party.

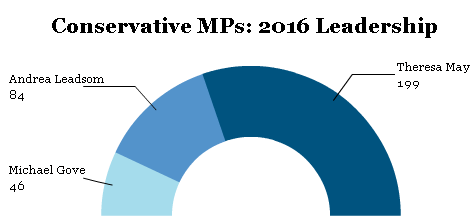

Monday brought another casualty of the post-Brexit era: energy secretary Andrea Leadsom, who withdrew from the September leadership contest for the Conservative Party leadership. The decision came just four days after Tory MPs pitted Leadsom (with 84 votes) in a runoff against home secretary Theresa May (with 199 votes), eliminating Gove (with just 46 MPs supporting him).

Leadsom, who supported the Leave campaign in the June 23 referendum, had garnered the support of the eurosceptic Tory right, including endorsements from former leader Iain Duncan Smith and other Leave campaign heavy-hitters like Johnson and even Farage. But Leadsom struggled to adapt to the public stage as a figure virtually unknown outside of Westminster a week or two ago (reminiscent in some ways of Chuka Umunna’s aborted Labour leadership campaign last year).

Though she promised to bring far more rupture to Conservative government than May, Leadsom also struggled to defend against charges that she embellished her record as an executive in the financial sector before turning to politics. Over the weekend, she suffered a backlash after suggesting she would be a better leader because she (unlike May) had children.

It was always an uphill fight for Leadsom, despite the rebellious mood of a Tory electorate that voted overwhelmingly for Brexit and was clearly attracted to Leadsom’s more radical approach. May, a more cautious figure, supported the Remain campaign during the referendum, though she largely avoiding making strong statements either for or against EU membership. At one point, she argued that the United Kingdom should leave the European Court on Human Rights (a position that she has disavowed now as a leadership contender).

So what happens next? And what do the prior 18 days portend for the policies and politics of the May government?

1. Leadsom’s lost opportunity

Leadsom had genuine appeal to the Tory grassroots (and not an insignificant share of UKIP’s core electorate) as a ‘change agent’ within the Conservative Party — though calling her the Tory version of Jeremy Corbyn somewhat misses the mark. Most of all, as the representative of the Leave campaign, she was well situated to argue that a Leave supporter is most appropriate to lead the negotiations to remove the British from the European Union. Though a Sky News poll late last week showed May leading Leadsom by a margin of 48% to 25%, Leadsom wasn’t doomed — that poll should have been considered a floor, not a ceiling. Leadsom showed every opportunity (in Johnson’s words, the ‘zap’) of making it a real race. But the most important effect of her withdrawal is that May will not be forced to spend two months making promises to win over a skeptical Tory right. That’s crucial to policy in the next 3.5 years.

2. ‘Brexit is Brexit’

Given May’s support for the Remain campaign, it was important for her to state unequivocally in her leadership campaign her commitment to respect the 52% of the British electorate that voted on June 23 to leave the European Union. But she has made it equally clear that she will not invoke Article 50 this year or at all until it’s clear what the British negotiation position will be. Don’t expect her to move fast. It will be impossible to disentangle over four decades of harmonization overnight. The United Kingdom, neither a member of the eurozone or the Schengen zone, already had a lighter footprint than most EU members.

*****

RELATED: Why British sovereignty would be even weaker

after leaving the European Union

*****

Expect the post-Brexit settlement, under May’s guidance, to look at lot like associate membership, if not exactly in name. There’s every indication that May will try to do what she can to retain British membership in the European single market, with full passporting rights (crucial to London and the British financial services industry). That means she will also likely accept, perhaps with limits and policy brakes, the principle of free movement.

3. Brexit is not May’s economic priority

It’s clear that, for many reasons, May is anxious to move Brexit from the headlines. Though she has pledged to create a new cabinet department headed by a secretary of state to lead Brexit negotiations, don’t expect the EU process to take center stage in the May government. May is wise to cultivate an attitude of insouciance about Brexit, because that will reduce any economic and financial panic over negotiations. But she also realizes that government cannot simply come to a halt for the next two (or three or ten) years solely for Brexit. She’s made it very clear that her government will take an activist role in boosting productivity, increasing the competitiveness of British exports and reducing inequality.

4. More Miliband than Thatcher on economic policy

May is already showering attention on the working class, especially in areas like housing affordability and inequality, in ways that wouldn’t be out of place in the policy seminars of the Labour Party under its former leader Ed Miliband. One of the consequences of the an aborted leadership contest is that May has the advantage of moving immediately to the center on economic policy. It’s a smart move, given the far-left orientation of Labour under Jeremy Corbyn, and it could mean that the Tories could occupy much of the center-left spectrum under a May government. May’s plan to increase the representation of workers on corporate boards seems particularly progressive. Though the comparisons between May and German chancellor Angela Merkel are overdone, this is right out of the Merkel playbook. Remember, too, that it was May who warned way back in 2002 the dangers of the Tories becoming the ‘nasty party.’

5. A solid end to the Cameron-Osborne ‘austerity’ regime

No one in 2016 thinks the United Kingdom is on the edge of a sovereign debt crisis, and one of the benefits of an early end to the Cameron era is that the Conservatives can back down from their commitment to austerity policies. Though May is hardly a neo-Keynesian when it comes to economic policy (she’s still a Tory!), she has also made it quite clear that she will do what she deems necessary to keep the economy afloat in the face of ongoing uncertainty over Brexit. Unlike Leadsom, who criticized the governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, May has praised Carney’s leadership in the aftermath of the EU referendum in maintaining a flexible approach to monetary policy to ensure access to credit markets. May hasn’t been shy about criticizing chancellor George Osborne, who has now backed down from a pledge to have a budget surplus by 2019-20. If May, with her eye on the next election, senses that the economy could be weakening, tax cuts or spending increases will take a priority over Tory commitments to fiscal discipline.

6. No early election

It’s clear that May has no stomach for evading the fixed parliaments law to hold early snap elections. It’s been 14 months since the electorate delivered a relatively strong mandate for Conservative leadership, and May — who was a senior member of the government that won reelection — has no incentive to plunge the country into yet another politically polarizing election season. It will be in May 2020. Though May could have easily called a snap election and, perhaps, benefited from a Labour Party divided over Corbyn’s leadership, it’s the smarter long-term move, politically speaking, to let Labour twist over Corbyn while May continues to move to the center on economic and social policy. In the meanwhile, it’s becoming harder and harder to believe that either Angela Eagle or Owen Smith can dethrone Corbyn in a leadership challenge this summer.

7. Question marks on foreign policy

May has been hawkish on foreign policy in the past. She voted to support the 2003 intervention in Iraq, and she consistently voted in favor of military strikes in Syria in the 2010s. Though it was the late Benazir Bhutto who introduced May to her husband, it’s clear that foreign policy is her weakest front — for now. Every prime minister grows into this role, to some degree. Though May has been on the front lines of the British fight against terrorism as home secretary, but we simply don’t know what May thinks about many international issues. We do know that she was willing to stand up to the United States — in 2012, she refused to extradite Gary McKinnon, a British computer hacker, much to the consternation of American authorities.

8. Less immigration

Expect May to attempt to institute more limits on immigration from outside the EU as well as trying to negotiate strict limits on EU migration in any future deal over British access to the European single market. That’s fully in line with her relatively hard stand on immigration as home secretary. Do not expect, however, that May will make the same mistake as Cameron by pledging to keep immigration under a certain number, which made Cameron look foolish when May’s home department found it impossible to meet that informal quota. Again, Leadsom’s withdrawal and Farage’s resignation as UKIP leader will give May much more flexibility.

9. ‘Safe pair of hands’ is absolutely correct

May is, by instinct a cautious moderate with a sharp personal sense of morality, and much is made of her upbringing as the daughter of an Anglican vicar and her commitment to public service as a calling (not unlike former prime minister Gordon Brown). As home secretary, she has erred on the side of a more authoritarian view of civil liberties, though no more than the Labour government that preceded her. In particular, she has proved particularly willing to call out police corruption and the inherent racism of stop-and-frisk policies, all while scrapping the despised Labour plan to introduce national ID cards. There’s no doubting that May is a conservative, but opponents will find it incredibly difficult to paint her as immoderate or incompetent. The immediate transition this week will give markets the stability they’ve craved since June 23.

10. Watch the cabinet picks

We will learn much about May in the next 24 hours when we find out who she has chosen to join her government. The current speculation has Osborne switching jobs with foreign secretary Philip Hammond, and that seems to fit well with May’s sense of continuity and stability (giving Osborne a face-saving exit from the treasury). Chris Grayling, a Leave proponent who nevertheless served as May’s campaign manager in the leadership campaign, is widely tipped to become the Brexit minister. May’s replacement as home secretary — perhaps energy and climate change secretary Amber Rudd or health secretary Jeremy Hunt — will also be telling. But also watch to see where (and if) May decides to appoint now-vanquished rivals from the Leave campaign like Johnson, Gove (currently justice secretary), Leadsom and Duncan Smith (until recently, work and pensions secretary). Also watch to see if she brings back David Davis, a one-time leadership contender and civil liberties champion, to the cabinet, and where the so-called ‘blue-collar Tory’ leaders like current work and pensions secretary Stephen Crabb and business secretary Sajid Javid wind up.