It took the counting of around 750,000 postal votes on Monday to settle what had been a too-close-to-call runoff to determine who would win Austria’s (mostly ceremonial) presidency.![]()

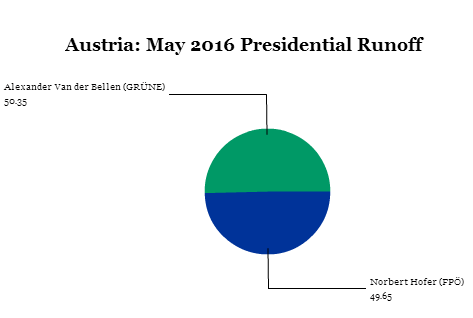

The winner, by a very narrow margin, is Alexander Van der Bellen, a 72-year-old professor and, nominally an independent, though formerly a parliamentary leader of the Die Grünen (Austrian Green Party), and you could almost hear the palpable sigh of relief from across the European Union as far-right presidential candidate Norbert Hofer conceded defeat.

But it’s a hollow relief.

The result means that Austria’s hard right will not occupy the presidency and, therefore, will not be able to attempt to terminate the current government or try to wrest greater powers from Austria’s parliament. But given the tumult of the past month in Austrian politics, the hard right has clearly been emboldened by the presidential race, and it will now look to the next parliamentary elections to take real power.

The first-round, double-digit victory of Norbert Hofer, the 45-year-old candidate of the right-wing, anti-immigrant Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ, Freedom Party of Austria), stunned not only Austria, but all of Europe. It represents the closest than any far-right party has come to winning power at the national level in the European Union since the 1930s.

* * * * *

RELATED: Far-right victory in Austrian presidential vote shocks Europe

* * * * *

Its success shouldn’t have been surprising. The Freedom Party has increasingly gained on the country’s mainstream parties, and it nearly toppled state governments in regional elections last autumn.

Despite its defeat, the FPÖ has been able not only to undermine a sitting chancellor, but to force his resignation. After social democratic chancellor Werner Faymann initially welcomed refugees to Austria last summer, he abruptly reversed course under pressure from the Freedom Party and angry voters, instead co-opting the rhetoric and the policies of the far right, complete with border fences and anti-immigration crackdowns.

But the candidate of Faymann’s center-left Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ, Social Democratic Party of Austria) finished in fourth place, and shortly after the first-round vote, the Social Democrats essentially forced Faymann to resign, bringing to an end an eight-year tenure leading a grand coalition government with the center-right Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP, Austrian People’s Party). For its part, the ÖVP presidential candidate placed an even more disappointing fifth.

Faymann, to his credit, ably led Austria through the 2008-09 global financial panic and the 2010 eurozone crisis, and Austria and its banking system, moreover, helped stave off a broader crisis in central Europe and the Balkans. Instead of leaving office, having made the noble case for welcoming refugees, he left power earlier this month after capitulating to the hard right.

His successor, Christian Kern, comes to the chancellery as the head since 2010 of the publicly owned Austrian Federal Railways. Under Kern’s leadership, both the ÖVP and the SPÖ are now clamoring to pass a series of reforms designed to boost jobs in the two years before the next parliamentary elections are due, before October 2018. Reinhold Mitterlehner, the leader of the People’s Party, will continue as vice chancellor and economy minister.

Kern himself is something of cipher, and it will be fascinating to watch how the first six months of his government unfolds. For what it’s worth, Kern has been a consistent defender of the kind of social values that have welcomed migrants to Austria with civility and warmth. Nevertheless, he has refused to rule out a potential future partnership with the Freedom Party. Kern, however, is said to favor relatively centrist, pro-business economic policies.

But voters seem to be genuinely wary of the cozy ties of the grand coalition, consensus-oriented governments that have dominated Austria’s postwar politics, and the FPÖ now represents the clearest opposition to the tradition parties of the left and the right. That matters in a country where party hierarchies have not only enjoyed a monopoly on state power but often access to jobs in the public sector, and party ties dominate Austrian business, academic and other spheres.

In fact, if elections were held today, the Freedom Party would easily come out on top — by a hefty margin. That means that its leader, Heinz-Christian Strache, who has rebuilt the party since the rise and fall of the late Jörg Haider in the early 2000s, might become Austria’s next chancellor. While the People’s Party governed in an informal alliance with Haider’s Freedom Party a decade ago (and was duly censured by the European Union), by 2018, it might be the Freedom Party calling the shots, and both the People’s Party and the Social Democratic Party have shown their willingness to bend to the far right.

If, by the time 2018 rolls around, Austria is facing the prospect of a powerful Strache-led government, moderates on the left and right might have wished, instead, that a symbolic Hofer presidency in 2016 could have deflated some of the growing pressure on Austria’s political system. They may well come to regret today’s narrow victory.

Van der Bellen’s presidential victory should give Kern the time and the space he needs to introduce reforms to win back Austrian voters. But the presidential vote showed a striking polarization — 86% of workers backed Hofer, while 81% of college-educated voters backed Van der Bellen.

The rise of the populist right isn’t, of course, an isolated phenomenon in Austria. Nationalists in the United Kingdom are waging a tough fight for the British to leave the European Union in 2016, and Marine Le Pen has long led first-round polls for France’s 2017 election. Populists are on the rise even in Germany. Hungary, Romania and Poland have all taken a turn toward the illiberal in recent years. But increasingly, as low GDP growth and pesky unemployment have depressed economic outcomes across the developed world, the dividing line in politics in the 2010s isn’t left or right, it’s a fight between nationalism and globalism, which is clear enough from the successes of businessman Donald Trump, the presumptive Republican presidential nominee in the United States.

So long as traditional left-wing and right-wing parties spend more time working together, and so long as stagnant economic growth threatens the health of the developed world’s middle class and an increasingly unprotected working class, a far-right candidate will win power in Europe. Maybe in Austria in 2018, maybe somewhere sooner. Hofer’s defeat today maybe be a temporary reprieve, but the forces that brought him to within a hair of the Austrian presidency are only growing stronger — above all in the unwillingness of centrists to stand up to isolation, nationalism and protectionism.