Though it’s only been two weeks since South Koreans upended polls to deliver a shock verdict in parliamentary elections, the country is now pivoting toward its next presidential election — which is nearly 20 months away. ![]()

Taking place nearly two-thirds of the way through the five-year term of president Park Guen-hye (박근혜), the election was an opportunity for Park to solidify her grip on the National Assembly, as well as her own party, the conservative Saenuri Party (새누리당, ‘New Frontier’ Party) by winning a more solid majority in South Korea’s 300-member unicameral legislature, the National Assembly (대한민국 국회).

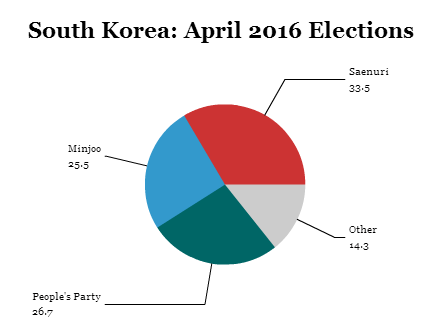

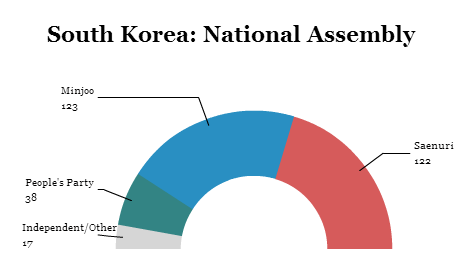

Despite poll predictions that Saenuri would take advantage of a split opposition and win an even wider majority, the party instead lost ground, falling further away from an absolute majority, winning just 122 seats, 24 fewer seats in the National Assembly than the party held before the elections. Park, like all South Korean presidents, is limited to a single term in office and, in some regards, she became a lame duck president from the first days of the 2013 inauguration of the country’s first female president. That hasn’t stopped Park from wielding power through a very strong executive branch.

Saenuri’s defeat, however, and Park’s failures in particular, mean that the country is now shifting towards the posturing among Park’s opponents, including those within other Saenuri Party factions, to plot a path to the presidency in an election that will not be held until December 20, 2017.

The results will give hope to the traditional center-left opposition party, the newly renamed (as of last December) Minjoo Party (더불어민주당), a successor to what used to be called the Democratic United Party, which won 123 seats — one more than Saenuri. That could embolden several top figures within the party to mount a 2017 presidential bid, including Moon Jae-in (문재인), the party’s former leader and its 2012 candidate against Park.

But the results will give even more hope to the newly formed, as of February, People’s Party (국민의당), an alternative liberal party that has pulled supporters away from Minjoo. Its leader is Ahn Cheol-soo (안철수), a software entrepreneur, businessman and academic, who burst onto the political scene as a potential presidential candidate in 2012. He will now almost certainly be a contender in the 2017 election. Though the People’s Party only won 38 seats, it actually won more votes than Minjoo.

So what does South Korea’s election mean for the rest of Park’s administration and for 2017?

Park’s last stand

Most immediately, the losses will make Park even more of a lame-duck president.

Sure, if a crisis erupts with North Korea, the country will rally around Park.South Korea has taken a firm stand against North Korea under Park and her predecessor, Lee Myung-bak (이명박), eschewing the softer ‘sunshine policy’ of the 1990s and early 2000s.

The South Korean president who just happens to be in office when (and if) North Korea’s autarkic totalitarian state falls will also be the one South Korean president to be remembered by world history for decades, possibly centuries, for the way he or she handles the inevitable integration of the Korean peninsula, in one form or another.

But so long as North Korea’s dictatorial leader Kim Jong-un (김정은) is still in power in January 2018, Park will likely leave office with a legacy far less consequential than her father, Park Chung-hee (박정희), a military rule who controlled South Korea from 1961 to 1979, who many Koreans credit for boosting the country’s economy and propelling South Korea into a high-income, highly developed country.

Critics, who have always feared Park as the daughter of an autocratic leader, have credibly argued that Park’s reign has curbed freedom of expression, and it’s true (and incredible) that online commenters were subject to censure by South Korean officials in the days leading up to the April 13 election. In December 2014, the South Korean constitutional court outlawed the Unified Progressive Party (통합진보당), a left-wing group, on suspicions of ties to North Korea and, in the process, further raising questions about democracy in the Park era.

Commentators who previously worried about Park’s grip on democracy perhaps shouldn’t have worried so much. Without a parliamentary majority, Park’s plans to liberalize labor laws and introduce other center-right reforms are now essentially dead. Despite fears that she would attempt to erode South Korean democracy, her presidency has been instead a series of missed opportunities and unforced errors, mostly notably a botched government response to the sinking of the MV Sewol ferry in April 2014, which ultimately killed 297 people. Efforts to appoint a new prime minister backfired when her first two nominees withdrew over ethics matters and controversial comments about Japan.

Though Park’s administration has also coincided with more North Korean nuclear tests, which Park has used to try to rally her country behind her, South Koreans seem far more occupied with a sluggish economy that has, like elsewhere in the global economy, driven income inequality and unemployment. Those concerns culminated last December in a series of anti-government rallies in Seoul that also opposed Park’s agenda to change the country’s history books.

Her defeat in the parliamentary elections, moreover, makes its unclear who will lead Saenuri in the next election.

Unlike in 2012, when Park’s ascendancy cleared the field, there’s no definitive successor waiting in the wings. In an incredible upset, one top 2017 contender, former Seoul mayor Oh Se-hoon (오세훈), lost a bid for a seat in the National Assembly. Elected in 2006 and reelected in 2010, he stepped down after losing a referendum to provide free lunches to the poorest 30% of the Korean capital’s children. (The opposition wanted to make free lunches available to all children).

Though party chairman Kim Moo-sung (김무성) will leave his position heading Saenuri later this year, though he could wind up with the presidential nomination himself.

Minjoo still divided over the past — and facing pressure from new forces

Though Moon Jae-in, the 2012 standard-bearer, remains in a strong position to lead the opposition into the 2017 election, he could face sharp competition in a party that’s now rechristened itself after years of stagnation.

Moreover, the party is still sharply divided over the legacy of Roh Moo-hyun (노무현), the last left-wing president of South Korea who, facing a corruption scandal, committed suicide in 2009, just one year after leaving office.

Moon, his former chief of staff, leads the informal pro-Roh faction.

Other contenders for the Minjoo nomination include the party’s chairman, Kim Chong-in (김종인), first elected to the National Assembly in 1981 and a former health minister, especially in light of the party’s surprising gains in the April parliamentary elections. Kim Boo-kyum (김부겸), a long-time centrist figure in Korean politics who defected from Saenuri’s predecessor (the Grand National Party) in 2003, recently won a seat in Daegu, Park’s home city and South Korea’s fourth-most populous.

But it’s Park Won-soon (박원순), who has been mayor of Seoul since October 2011, who presents the likeliest challenge. A longtime human rights activist and academic, he was an independent before joining forces with Minjoo upon his election as mayor, and he can most easily characterize himself as an outsider — not unlike Ahn.

Ahn remains a wild card for 2017

He’s been called the ‘Bernie Sanders’ of South Korea, but in many ways, Ahn Cheol-soo is more like Ross Perot, a vaguely centrist outsider who parachuted into politics from the business world. Ahn founded AhnLab, Inc., an antivirus software company, and before formally entering politics, he served for a time as a graduate school dean at Seoul National University.

If there’s one clear winner from the 2016 parliamentary elections, it’s Ahn and his new party, which won nearly 27% of the vote and over three dozen seats in the National Assembly.

Neither too far left or too far right, Ahn’s platform is more about providing a change in perspective from South Korea’s polarized politics than ten-point policy briefings. Incredibly, for the better part of five years, Ahn has maintained a reputation as somewhat above the political fray, even while he’s maneuvered back and forth like a political pro.

In 2012, he suspended his presidential campaign in favor of Moon to prevent the anti-Park vote from splitting (a plan that, obviously, failed when Park easily defeated Moon). From 2014 through last December, Ahn joined his anti-politics, outsider movement with the center-left Democrats to form a so-called ‘New Politics Alliance for Democracy.’

When that alliance also failed, Ahn created the People’s Party that fared so well in the most recent elections. While Minjoo managed to make gains in Seoul and Gyeonggi, the populous region that surrounds Seoul, Ahn’s new People’s Party made gains in southwestern Jeolla province, which had long been a stronghold of the Democratic United Party (Minjoo’s predecessor).

It’s frankly impossible to imagine any Minjoo presidential candidate winning in 2017 without ample support in Jeolla.

Likewise, Ahn’s unprecedented support, in Jeolla and elsewhere, has now turned South Korea into a genuine tripartite democracy, at least for the time being. Even if Minjoo puts up its most charismatic and popular leader (for now, that’s probably Moon Jae-in or Park Won-soon), Ahn could easily consolidate anti-Saenuri support, especially among young and urban voters, to win the presidency.

With just 38 seats in the National Assembly, however, Ahn would have to partner with the Minjoo Party to achieve any legislative accomplishments, and it’s possible that, like in the waning days of 2012, and during the short-lived alliance of 2014 and 2015, Ahn’s party and Minjoo could once again join forces in 2017. This time around, however, it just might be Ahn’s polling strength that forces the Minjoo candidate to drop out.

Another wild card in Turtle Bay

Though he isn’t part of the day-to-day grind of Korean politics, there’s still one favorite among all potential candidates: Ban Ki-moon (반기문), the United Nations secretary-general whose term ends at the end of 2016. For years, Ban, by now a Korean statesman, has led presidential polls by huge margins, precipitating so much speculation that Ban himself asked the media to refrain from the rumor-mongering.

Ban, who studied under Joseph Nye in the 1980s at the John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University, spent an entire career in diplomacy, serving in various United Nations roles, as deputy ambassador to the United States, South Korea’s national security advisor, an ambassador to Austria and Slovenia. He served as foreign minister of South Korea under Roh Moo-hyun, and he was instrumental in leading the so-called ‘six-party’ talks that, for a time, calmed the nuclear tension between the two Koreas.

As secretary-general, Ban has called for global acceptance of LGBT rights, and while he’s spent more time dealing with Iran, Syria and the Middle East than east Asia, he has also tried to use the UN’s top role to nudge North Korea, however unsuccessfully, to the negotiating table.

With such a high profile, Ban will have as much time as he wants in 2017 to decide about a presidential campaign when his stint at the United Nations ends. Though he served as foreign minister to a left-wing president, he also has ties to Saenuri. If he decides to run, however, he could realistically take his pick from among South Korea’s parties — or he could run as an independent.

The truth is that the presidential field cannot be settled until mid-2017 when Ban’s decision is clear. His poll lead now means little for an election that will take place in December of next year, and if he does run, he’ll face questions about the connection between his family’s wealth and his own positions.