In the aftermath of a difficult national election that could well lead to fresh elections across all of Spain, Catalonia, the northeastern region with a swelling independence movement, was always set to be the largest puzzle piece that patches together any potential coalition to lead the national government. ![]()

![]()

Now the region will take center stage even more fully in Spain’s unfolding political drama, with a high-stakes game of chicken reaching its peak this week between regional president Artur Mas and the left-wing Candidatura d’Unitat Popular (CUP, Popular Unity Candidacy). The pro-independence CUP has refused to lend its support to the larger pro-independence coalition, Junts pel Sí (Together for Yes), the broad, pan-ideological group that won last September’s elections.

The CUP’s leaders have for months maintained that they will not — and politically cannot — support Mas, a center-right regional leader who has skillfully attached himself to a sovereigntist movement that’s now dominated by figures on the Catalan left. He’s the ideological heir to a political elite that, under his predecessor, Jordi Pujol (regional president from 1980 to 2003), became synonymous with corruption. Moreover, as regional president since 2010, Mas has introduced tax increases and budget cuts designed to keep the region’s fiscal condition from deteriorating, even as the wider Spanish economy collapsed, taking the Catalan regional economy with it.

* * * * *

RELATED: Madrid ignores Catalan vote at grave risk

RELATED: Catalan election results: pro-independence parties win narrow majority

RELATED: Three choices for new, fractured Spanish political landscape

* * * * *

On Sunday, the CUP — a radical left group that would oppose an independent Catalonia’s membership in either NATO or the European Union — reiterated that it cannot support Mas for regional president and that it will block investiture of Catalonia’s executive government, the Generalitat, forcing new spring elections, so long as Mas is determined to lead it. Indeed, Mas has refused to step aside. If no one budges between now and January 10, Catalonia will hold fresh elections (along, perhaps, with Spain after the fractured result of the December 20 national elections). For Catalans, it would be the fourth regional election in five years.

But if there’s one thing that Junts pel Sí doesn’t lack, it’s a deep bench of political leaders, each of whom could easily step in as a regional president far more amenable to the radical CUP and its supporters, thereby forming a truly broad pro-independence front. If Mas doesn’t back away in favor of another of his coalition’s leaders, fresh elections could actually leave Catalonia’s parliament even more divided, potentially setting back the independence movement that he claims to represent. And that should tell you exactly where Mas’s heart lies — in maintaining power at all costs, not seriously advancing an independent Catalonia.

By forcing spring elections, Mas risks, first, prolonging the process of building both a national Spanish government and a regional Catalan government, and, secondly, discrediting the independence movement itself. Mas first embraced the independence cause in 2012 after widespread September protests against Madrid, a movement that Mas co-opted to win reelection two months later. It was, at the time, a masterful political move, because Mas effectively shifted blame for ‘austerity’ from his own government to the national one in Madrid. Powerful protests against unemployment and economic malaise combined with long-simmering resentment among Catalans, who feel that they spend far too much of their regional wealth boosting the coffers of Spain’s central government and poorer regions. Given the economic strain on Catalans in the midst of the eurozone sovereign debt crisis, it wasn’t surprising that the independence movement gathered steam, and Mas shrewdly jumped on the bandwagon, much to his political benefit.

Having staked his premiership on Catalan sovereignty, however, Mas spent much of 2014 pushing a vote for Catalan independence in what prime minister Mariano Rajoy maintained was illegal under Spain’s constitution. Although Rajoy and Mas come from the same political ideological tradition, they both had political incentives to draw a hard line against potential solutions, including the most obvious — a more federal Spain with greater regional autonomy.

When Spain’s constitutional court ruled that the referendum was, in fact, illegal, Mas canceled the vote as a binding plebiscite. But he moved ahead with a non-binding vote instead that hedged bets by asking two convoluted questions, not a direct up-down vote on independence. Nevertheless, Rajoy’s stubborn approach has undoubtedly bolstered the separatist cause, especially in contrast to the 2014 referendum on Scottish independence agreed between Scotland’s regional government and Westminster.

As Mas came to embrace a more radical perspective on breaking from Spain, it also caused strain between the two wings of the coalition that had dominated Catalan politics since the late 1970s, Convergència i Unió (CiU, Convergence and Union), which ultimately split in mid-2015.

Mas’s party, the more nationalist Convergència Democràtica de Catalunya (CDC, Democratic Convergence of Catalonia) entered into Junts pel Sí, a broad, pan-ideological coalition with the rising Esquerra Republicana de Catalunya (ERC, Republican Left of Catalonia) and other pro-independence groups for the September 2015 regional elections. Junts pel Sí begrudgingly accepted Mas as its candidate for regional president, provided that all parties agreed that a majority for Junts pel Sí would amount to a mandate for an 18-month timetable to Catalan independence.

It was a success, mostly — Junts pel Sí won an overwhelming victory on an explicitly pro-election mandate, but without an absolute majority and just six seats short of a majority in the Catalan regional parliament.

Nevertheless, it was neither Mas nor the ERC’s leader, Oriol Junqueras, who led the movement to such a super result, but a former member of the European Parliament, UNESCO policy expert and green activist, Raül Romeva. If Mas’s most important goal truly were advancing the pro-independence movement, he would have stepped aside long ago in favor of Romeva, whose leftist orientation makes him more representative of the Junts pel Sí coalition and more in line with the CUP.

Adding to the confusion is the result of the national election, which split four ways among the two longstanding political parties in Spain, Rajoy’s Partido Popular (PP, People’s Party) and the center-left Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party), and two new upstart parties, the left-wing, anti-austerity Podemos (We can) and the center-right, liberal Ciutadans/Ciudadanos (‘Citizens’ or just the ‘C’s’), a party founded in Catalonia that opposes independence and that competed nationally for the first time in Spain’s December 20 vote.

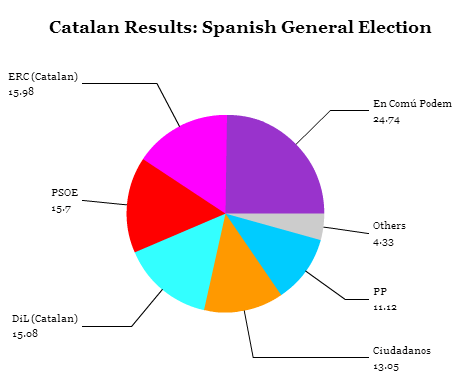

In Catalonia, the vote was even more fragmented — six parties won between 10% and 25% of the vote. The most successful was neither the left-wing separatist ERC or Mas’s party, newly rechristened as Democràcia i Llibertat (Democracy and Liberty), but the local Podemos-affiliated En Comú Podem, a coalition of anti-austerity activists and local Catalan greens and leftists that, earlier in 2015, fueled Ada Colau to the mayor’s office in Barcelona. The far left easily outpaced the ERC and the DiU, and even Ciudadanos, which won nearly 18% of the regional parliamentary vote in September, won just 13% in the December election. Colau, since becoming mayor in June, has worked to fulfill her pledge to slow evictions in the picturesque Catalan capital.

The result suggests that, if snap elections are held in Catalonia, the Podemos-affiliated far left will do even better than in September.

It’s an important lesson at the national level, too, for Pedro Sánchez, who hopes to become prime minister by forming a left-wing coalition of the kind that, however improbably, made Portuguese Socialist leader António Costa prime minister in November. Ironically, one of the most important gaps between Sánchez, the PSOE leader, and Podemos, is the latter’s insistence on a free vote for Catalonia on independence, a step Sánchez staunchly refuses to consider (though unlike Rajoy, Sánchez is open to discussions about greater autonomy and federalism). Ironically, the differences between Spain’s two leftist parties on Catalan independence could also force snap elections nationally this spring as well.