In a more developed democracy, Côte d’Ivoire’s October 25 election might have been a civil rematch of the 2010 contest between the incumbent, Alasanne Ouattara, and his fierce rival, former president Laurent Gbagbo.![]()

Instead, Gbagbo is imprisoned at The Hague in The Netherlands awaiting trial at the International Criminal Court as the first head of state to be tried for crimes against humanity that stem from Gbagbo’s refusal to step down from the Ivorian presidency after the 2010 elections, setting the country into its second civil war in a decade as Gbagbo and his allies clung to power.

Captured in 2011 by UN and local forces loyal to Ouattara, Gbagbo still retains a loyal following, and supporters want to see Gbagbo freed.

Instead, Ouattara easily won the presidential vote, election officials announced last week, effortlessly dispatching Pascal Affi N’Guessan, formerly prime minister under Gbagbo from 2000 to 2003 and a longtime Gbagbo supporter.

Ouattara, of northern descent, served as Félix Houphouët-Boigny’s final prime minister from 1990 until the former president’s death in December 1993. Though he attempted to run for president in 1995 and 2000, opponents like Robert Guéï, the country’s military leader from December 1999 to October 2000, managed to have him barred from the race on specious charges that Ouattara was actually born in neighboring Burkina Faso, inflaming northern Muslims by implying that they are something less than fully Ivorian. An economist, Ouattara spent the late 1990s at the International Monetary Fund, where he rose to the rank of deputy managing director. The struggle over the 2000 election and its aftermath directly led to the civil war that broke out in 2002.

Former president Laurent Gbagbo, who once represented the hopes of the Ivorian opposition, now sits in The Hague awaiting an ICC trial for crimes against humanity.

Ouattara officially won 82.66% to just 9.29% for N’Guessan, though many of Gbagbo’s supporters boycotted the vote. That means that the lopsided victory obscures the fact that Côte d’Ivoire remains highly divided on north-south lines.

Though it might have been a less-than-scintillating contest, it is perhaps remarkable that the country made it through an election without major violence — a consequence aided by the fact of an ongoing 6,000-strong UN peacekeeping force, an international presence for over a decade.

Though Ivorian elections were held consistently every five years since independence from France in 1960, Houphouët-Boigny dominated them as the only candidate on the ballot — that is, until the introduction of multi-party democracy in time for the 1990 elections, when Gbagbo, then a dissident voice and history professor, became the first candidate to challenge Houphouët-Boigny.

A classic ‘big man’ autocrat, Houphouët-Boigny presided over a prosperous economy for nearly two decades, as cocoa, coffee and other agricultural exports prospered. High GDP growth and an influx of post-independence investment from France boosted the growth of the west African country’s manufacturing sector as well. French residents to Côte d’Ivoire actually increased in the years after independence, as Houphouët-Boigny welcomed industrial, developmental and policy expertise from French advisers.

The collapse in commodity prices in the late 1970s and early 1980s, however, took its toll on the country, which entered a prolonged economic slump just as Houphouët-Boigny accelerated the country’s spending on infrastructure and sometimes outlandish projects.

The country seemed to weather Houphouët-Boigny’s death in 1993 relatively well, at least at first. It coincided with a brief return to the breakneck economic growth of the 1960s and the 1970s, and the ruling party’s successor, Henri Konan Bédié, was an experienced figure with decades of experience, including as finance minister during the Ivorian boom). Guéï ousted Bédié six years later, however, launching Côte d’Ivoire into a decade of devastating instability.

By the time of the 2000 elections, Gbagbo’s mostly Christian supporters in the south were at war with Ouattara’s primarily Muslim supporters in the north. By 2002, political and religious violence had devolved into full-fledged civil war, as international media reports revealed the prevalence of child slave labor in the country’s cocoa plantations and extrajudicial killings during the 2000 presidential election campaign. After several false starts at peace talks, UN peacekeepers first arrived in 2004, though it would be 2008 before northern forces began disarming. Gbagbo won the highly contentious first round of the 2010 presidential election, however narrowly, and he refused to concede when Ouattara narrowly won the second round, bringing the country once again into civil war.

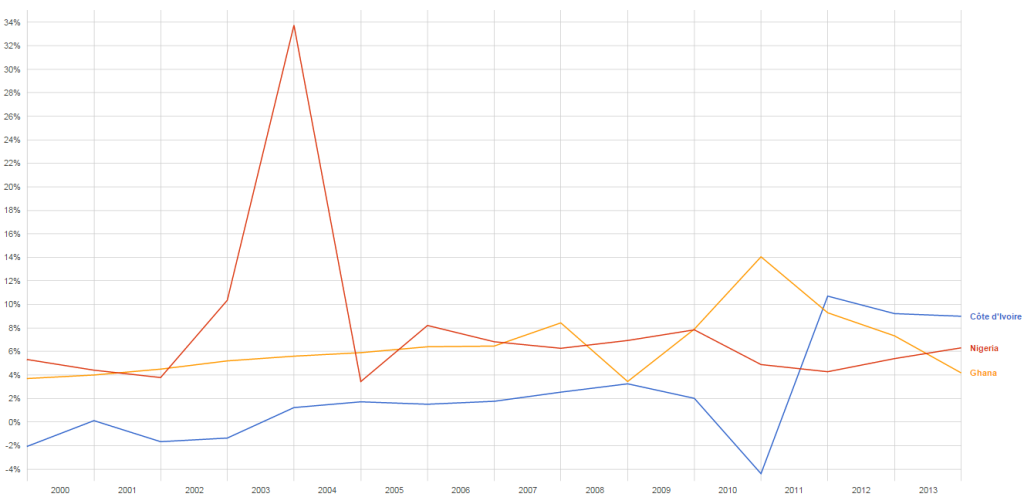

Since 2011, however, Ouattara has overseen the return of something like peace and economic prosperity, with GDP growth rates of around 8% in a country that is once again the world’s largest cocoa producer. Perhaps the most symbolic sign that Côte d’Ivoire is ‘back’ as a stable and prosperous country is the return of the African Development Bank to its headquarters in Abidjan, the country’s largest city and commercial heart. After years of underperformance, ing, Côte d’Ivoire is now outpacing even emerging economies like Nigeria.

But Ouattara is term-limited and, while term limits have proven fluid in sub-Saharan Africa, at age 73, it’s not clear that Ouattara would even want to stick around in power after 2020, when he will be 78 years old. His challenge in the next five years is to put Côte d’Ivoire on a footing for the kind of institutional stability that will outlive the Ouattara administration. Failure to do so could find the country falling back into the familiar violence that so plagued it in the 2000s. Wide developmental disparities mean that economic opportunities are lopsided throughout the country. The national military isn’t incredibly strong, and disarmament processes still haven’t reduced the wide access to arms throughout the country, which could make any future tensions all the more violence.