August may be among the most quiet periods of the year for world politics, especially in Europe as workers spend weeks away on holiday. ![]()

![]()

But events earlier this week made it very likely that two Mediterranean countries could hold snap elections later this year, adding greater political uncertainty to a European electoral calendar that will see elections for a new Labour leader in the United Kingdom next month, a new regional government in Catalunya (with implications for the Catalan independence movement) and new national governments in Portugal, Poland and Spain.

Greece’s troubled far-left government may call a vote of confidence as it begins implementing the country’s third bailout package, finalized with European leaders last weekend despite onerous conditions that could retard economic growth for years. The bailout and its aftermath could split prime minister Alexis Tsipras’s ruling SYRIZA (Συνασπισμός Ριζοσπαστικής Αριστεράς, the Coalition of the Radical Left). With far-left SYRIZA rebels already opposed to the bailout and with other opposition parties refusing to prop up Tsipras’s government, Greece could be forced to hold its second election since January, when SYRIZA first swept to power.

Across the Aegean Sea, Turkey may find itself forced to hold a repeat election after the ruling Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) of president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu (pictured above) apparently failed to find common ground with Turkey’s two largest opposition parties, leaving it just shy of a majority in the Turkish parliament. Without a working majority, Erdoğan may be forced to call a new election by August 23, when Davutoğlu’s mandate to form a coalition government expires.

In both cases, the most recent polls show that voters would likely return the same parties to power in roughly the same proportions. So the vital question is how Tsipras and the AKP would shake up their respective electorates before fresh polls.

Tspiras 2.0?

In Greece, the backdrop to early elections is whether the country’s third bailout, which will unlock up to €86 billion in financing for the near-bankrupt state, will split SYRIZA. Though the decimated ranks of Greece’s center-left and center-right backed Tsipras (pictured above) initially in the Hellenic Parliament, where SYRIZA controls just 149 seats (out of 300) and its anti-austerity right wing partner, the Independent Greeks (ANEL, Ανεξάρτητοι Έλληνες), controls just 13 more seats.

* * * * *

RELATED: Three ways Europe and Greece could blow their last chance at a debt deal

RELATED: If ‘Grexit’ comes,

Greece will have wasted five years in depression

* * * * *

Tsipras only begrudgingly accepted the bailout terms, following an election pledge to end the era of bailouts and austerity. Faced with poor terms by late June or, essentially insolvency, Tsipras called a referendum for July 5. Though the Greek electorate delivered him a surprisingly strong ‘no’ vote against the terms on offer, a weeks-long bank holiday and a group of European leaders unwilling to offer debt relief forced Tsipras’s hand — he could either accept the austerity conditioned on yet another bailout or he could force even harsher economic conditions that would come from Greece’s exit from the eurozone.

Not everyone in Tsipras’s party agrees. Last week, his pro-bailout cadres dipped below 120 MPs — a crucial mark for any future confidence vote. Though the center-left and center-right continued to back Tsipras’s efforts to implement Greece’s third bailout, they’ve made it clear that they will not support Tsipras. Even if the opposition parties abstained, thereby giving Tsipras more breathing room to deal with SYRIZA rebels, it’s not clear that Tsipras would win a confidence vote with nearly one-third of his party still defecting.

SYRIZA’s left flank, led now by former finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, former energy minister Panagiotis Lafazanis and parliamentary speaker Zoe Konstantopoulou, seems poised to break from SYRIZA and, in any event, remains committed to opposing a fresh bailout, no matter the consequences.

A Tsipras-led SYRIZA today commands a nearly 20% margin over the center-right New Democracy (ND, Νέα Δημοκρατία). But because there’s a 50-seat ‘winner’s bonus’ for the political party that wins the highest share of the vote, a divided SYRIZA might well forfeit first place to New Democracy — especially if former television news reporter Stavros Theodorakis and his new center-left movement, Το Ποτάμι (To Potami), woos moderate voters away from Tsipras.

Those variables may all be enough to force Tsipras to think twice about calling a confidence vote because a formal divide within SYRIZA (and its resulting defeat) could be a disaster for the European left. In the words of New Democracy MP Kyriakos Mitsotakis, while SYRIZA promised to tear up the [bailout] memoranda during the campaign that led to its January election, ‘now the Memoranda are tearing up SYRIZA.’ A hung parliament, moreover, could leave the bailout in doubt, dragging Europe and Greece once again considering the existential realities of a ‘Grexit’ — and further delegitimizing the European Union’s democratic underpinnings.

If, alternatively, a more pragmatic Tsipras can lead the core of his party (minus the most left-wing rebels) to a fresh victory before voters feel the pain of the new austerity measures, he could reinvent his premiership. Loosed from the hard-left Marxists in SYRIZA, he could conceivably eschew the nationalist ANEL and form a centrist government with To Potami and, perhaps, the withered Panhellenic Socialist Movement (PASOK, Πανελλήνιο Σοσιαλιστικό Κίνημα).

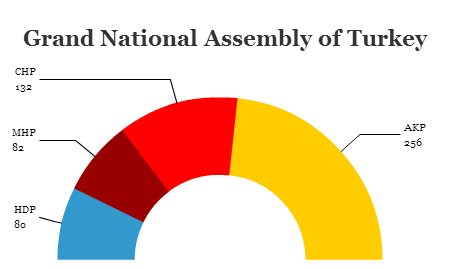

Meanwhile, in Ankara, the AKP has been reeling after it won just 256 seats in the Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (Grand National Assembly) — just 20 short of a majority. The June 7 elections forced a return to coalition politics, an unfamiliar position for Turkey after the AKP’s uninterrupted 12-year rule.

Talks with both the center-left Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party), the largest opposition party, and with the right-wing, nationalist Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP, Nationalist Movement Party) seem to have failed. It’s not surprising, given that both the CHP and the MHP represent the remnants of the failed ‘Kemalist’ secularism that Erdoğan’s 2002 victory essentially ended, to the delight of conservative Islamists as well as liberals. The CHP, in particular, opposes Erdoğan’s push to consolidate presidential power, its activist anti-Assad foreign policy in Syria, the turn from NATO and the European Union and the gradual introduction of socially restrictive laws catered to the AKP’s Islamic base.

Reports suggest that the AKP sought little more than support for a minority government or a short-term government that would prepare Turkey for new elections in a few months’ time.

* * * * *

RELATED: Coalition politics returns to Turkey after AKP loses majority

* * * * *

Snap elections would come, however, at a sensitive time for Turkey, which escalated its attacks on ISIS, joining the US-led bombing campaign against the radical group in late July after an ISIS incursion in the Kurdish-majority city of Suruç. Unfortunately, the Turkish assault coincided with a separate attack on the Partiya Karkerên Kurdistanê (PKK, Kurdistan Workers’ Party), an armed Marxist group. Tensions are rising as the PKK’s leaders blame the Turkish government for ISIS’s rise in southeastern Turkey.

The skirmishes between Turkey’s military and the PKK now threaten to roll back what had been a productive peace process. Growing trust between the AKP and Turkey’s Kurdish minority and relaxing restriction on the use of Kurdish language and culture in education, rank among most important legacies of the Erdoğan regime. More strategically, Erdoğan has benefited from the Iraqi Kurdish attacks on ISIS in Syria and Iraq, despite the official tension between Turkey and its Kurdish minority. All of that is now at risk.

Turkish Kurds, in fact, have the most to lose from new elections. Under the charismatic leadership of Selahattin Demirtaş (pictured above), the left-wing, Kurdish-interest Halkların Demokratik Partisi (HDP, People’s Democratic Party) won over 13% of the vote and 80 seats in the Turkish national assembly — the first time that a Kurdish party surpassed the 10% hurdle for representation. It was a milestone insofar as it brought the grievances and issues of Turkish Kurds into mainstream political discourse as an alternative to the PKK’s guerrilla option. But in a snap vote, the AKP will almost certainly target the HDP’s supporters (who once supported Erdoğan over the secular Kemalists). That puts Demirtaş, the voice of Kurdish democratic inclusion, in a very uncomfortable spot.

If Erdoğan, over the course of a few months, manages to re-engage the PKK as a military matter and maneuvers the HDP out of its hard-won political representation, the AKP could erase the gains of a decade of careful and thoughtful diplomacy both to Turkish Kurds internally and Iraqi Kurds externally — a result that would add even more burdens to an already overwhelmed region.