Not so long ago, British prime minister David Cameron suggested that his Danish counterpart, Helle Thorning-Schmidt, would make a good alternative candidate for the presidency of the European Commission.![]()

Thorning-Schmidt (pictured above) demurred the speculation. Ultimately, European leaders embraced former Luxembourg prime minister Jean-Claude Juncker and instead of seeking a safe job in Brussels, Thorning-Schmidt became increasingly convinced that she could lead her center-left government to reelection in a vote originally expected in September.

A Rorschach test for EU economic policy?

Thorning-Schmidt called snap elections for June 18, hoping to take advantage of a growing sense of momentum. Indeed, she may have taken a different sort of comfort from Cameron, who last month won an even stronger mandate for a second term in his own general election. After a period of GDP contraction and fiscal tightening, Thorning-Schmidt is betting that nascent economy recovery and the promise of greater welfare spending in the years ahead will be enough to replicate Cameron’s feat in Denmark.

If she succeeds, both sides on the European debate over economic policy will try to claim victory. For the European center-right, a Thorning-Schmidt victory would provide more evidence that an electorate is willing to reward a government’s hard grind to demonstrate fiscal stability. For the European center-left, it would show the way forward for social democrats struggling to salvage, reform and reinvent the welfare state in an age of austerity.

Furthermore, as the second-most populous Nordic country, Denmark (with 5.7 million people) is a weathervane of all the recent political, cultural and economic trends across northern Europe — and where the region may be headed.

How Helle turned a near-certain defeat into a dead heat

Thorning-Schmidt is the leader of the Socialdemokraterne (Social Democrats), the largest party on the Danish left, and she leads an informal ‘red’ coalition of parties that may be willing to join forces for a broad leftist government after the election. Not surprisingly, she won sympathy from voters in the wake of a radical Islamic attack on a Copenhagen cafe and synagogue in February. Moreover, she is hoping that forecasts of 1.5% or greater GDP growth will overshadow the GDP contraction and fiscal contraction that marked the first half of her government.

Thorning-Schmidt, who might be most well-known to Americans for joining Cameron and US president Barack Obama in a ‘selfie’ at Nelson Mandela’s funeral, is the country’s first female prime minister, drawing more than a few comparisons with Birgitte Nyborg, the fictional prime minister in the unlikely hit television show Borgen, a drama about Danish politics that developed a fan base across Europe, the United Kingdom and even the United States. She is married to Stephen Kinnock (the son of former British Labour leader Neil Kinnock), who recently won a seat as a Labour candidate in a Welsh constituency in the May 7 British election.

Unlike Nyborg, however, Thorning-Schmidt often struggled in her first term among the woes of a depressed economy, the management of a minority government and seven cabinet reshuffles in her first two years alone. Critics dismissed her as ‘Gucci Helle’ for her glamorous wardrobe, and polls throughout 2012 and 2013 gave the conservative opposition a double-digit lead.

Today, however, the Danish right’s lead has evaporated.

Thorning-Schmidt now benefits from the lackluster popularity of her chief adversary, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, the leader of Denmark’s chief center-right party, Venestre (Liberals), who succeeded Anders Fogh Rasmussen when he left Danish politics in 2009 to become NATO secretary-general. The second Rasmussen (pictured above), who was never as popular as the first Rasmussen, is weakened by credible accusations of inflated expense spending. What’s more, Thorning-Schmidt implemented tough fiscal reforms in 2012 with the support of his party, partially usurping the center ground of economic liberalism.

Danish far-right remains a factor on immigration and EU policy

She’ll also benefit from attempts to co-opt the rhetoric of the far-right, eurosceptic Dansk Folkeparti (Danish People’s Party) in subtle ways — she agrees, for example, that immigrants to Denmark should find work. Though the Danish People’s Party won the largest share of the vote in the May 2014 European parliamentary elections, polls show that its share of the vote is somewhat lower a year later. The party is still expected to maintain its role as Denmark’s third-largest parliamentary bloc.

Though it’s still fiercely anti-Muslim and wants to limit immigration sharply, the party has shifted its focus to the European Union, calling for an in-out referendum of the kind that Cameron has promised to allow in the United Kingdom in 2017. Though Denmark is not a member of the eurozone, it has negotiated opt-outs from certain aspects of the EU justice regime, and it’s likely that the country will hold a referendum next year, no matter who wins next week’s vote, on the more narrow question of embracing the policies that would allow for more cooperation with European police efforts. British policymakers on both sides of the ‘Brexit’ question will be watching closely as the 2016 Danish referendum unfolds.

What a ‘red’ coalition would mean

Though the Social Democrats have developed a significant lead in the polls, Thorning-Schmidt’s potential allies are struggling. In the 2011 election, Thorning-Schmidt became prime minister even though Rasmussen’s Venstre won more votes than the Social Democrats. In an ironic twist, Rasmussen could become prime minister in 2015, even if the Social Democrats win the largest vote share. If so, Thorning-Schmidt’s misfortune will be due to the flagging performance of Denmark’s other leftist parties.

They include the moderate Radikale Venstre (Social Liberals), whose former leader Margrethe Vestager left her post as deputy prime minister and minister of the economy and interior last September to become the European commissioner for competition, a high-profile role where she hasn’t shied away from bringing charges against the likes of Google or Gazprom. Though Vestager is perhaps even more popular than Thorning-Schmidt (Vestager often overshadowed the premier as economy minister), her successor Morten Østergaard has struggled to develop a strong connection with Danish voters.

Thorning-Schmidt’s allies also include the Socialistisk Folkeparti (Socialist People’s Party), which left the coalition in 2014 in protest of the government’s decision to sell around 18% of Denmark’s public energy company, DONG (Danish Oil and Natural Gas) to the US investment bank Goldman Sachs.

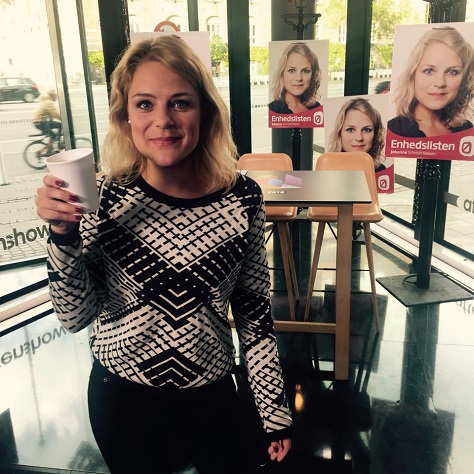

To the extent that Thorning-Schmidt shifts leftward in a second term, she might also look to two additional parties for support. The first is the Enhedslisten – De Rød-Grønne (Red-Green Alliance), whose informal leader, the 31-year-old Johanne Schmidt-Nielsen is one of Denmark’s most popular rising stars. Thorning-Schmidt’s decision to call an election in June came just a few days before an internal Red-Green Alliance deadline that limits its legislators from running for reelection after a seven-year period, thereby allowing Schmidt-Nielsen (pictured above) one more term in parliament under her party’s rules. It’s a shrewd move on Thorning-Schmidt’s part that could woo the handful of voters she’ll need in the broad fight between the Danish right and the Danish left.

The second is a new party, Alternativet (The Alternative), a center-left party founded in 2013 by a former culture minister and former Social Liberal, Uffe Elbæk.

What a ‘blue’ coalition would mean

Venestre governed for a decade in the 2000s with the informal support of the Danish People’s Party, and it would likely do so again if Rasmussen and his allies look like they can achieve a majority with the Danish People’s Party’s support.

Rasmussen’s ‘blue’ coalition would include two smaller parties, the Konservative Folkeparti (Conservative People’s Party) and the Kristendemokraterne (Christian Democrats), but the partner everyone is watching is the Liberal Alliance, a libertarian party founded in 2007.

In its first election, the Liberal Alliance won 2.8% and five seats. Its support rose to 5.0% and nine seats in 2011, and polls show it could win between 6% and 9% this year. In the cozy world of Danish consensus politics, the party attempts to appeal to young Danes, in particular, with calls to rethink the country’s high-tax, high-service, high-regulation approach. It could ultimately mark the largest gains of any party between 2011 and 2015. If so, its leader, Anders Samuelsen (pictured above), another former Social Liberal, could become Denmark’s next finance minister — and an instant star of European economic liberals in the vein of Belgium’s Guy Verhofstadt or Finland’s Olli Rehn.

Nevertheless, a Rasmussen-led coalition would probably share more continuity than rupture with Thorning-Schmidt’s approach. It would maintain her fiscal policy with marginally less spending, with perhaps a slightly feistier attitude to immigration, benefits and the EU-Danish relationship on criminal justice matters.

Voters will elect all 179 members of the Folketing, Denmark’s unicameral parliament — 175 from Denmark and two each from the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Most legislators are elected across 10 multi-member constituencies through proportional representation. An additional 40 seats are reserved to smooth out the results in a way that reflects the national vote.

I’ve been using https://www.nothingbuthemp.net/collections/cbd-gummies daily seeing that over a month nowadays, and I’m truly impressed during the absolute effects. They’ve helped me perceive calmer, more balanced, and less tense everywhere the day. My sleep is deeper, I wake up refreshed, and uniform my core has improved. The value is famous, and I appreciate the accepted ingredients. I’ll obviously preserve buying and recommending them to the whole world I identify!