You will not find the name of Turkey’s president, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, on any ballot during the June 7 Turkish general election.![]()

Make no mistake, however — Sunday’s vote is nothing short of a referendum on Erdoğan’s 12-year rule, creeping authoritarianism, mild (and sometimes not-so-mild) Islamism and, above all, his plans to change the Turkish constitution to redistribute more power to the presidency and away from the legislature.

* * * * *

RELATED: How Turkey’s Kurds became a key constituency in election

RELATED: Erdoğan wins first-round presidential victory

* * * * *

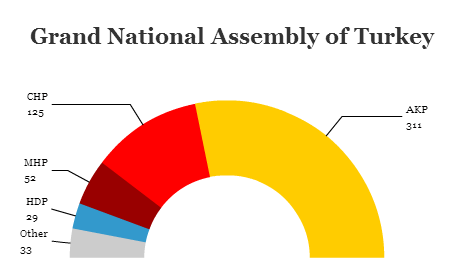

Barring a surprise, however, Erdoğan and the ruling Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi (AKP, the Justice and Development Party) will almost certainly fail to win the two-thirds majority of seats in the 550-member Türkiye Büyük Millet Meclisi (Grand National Assembly) to impose constitutional reforms. So long as the AKP controls the Turkish parliament, however, Erdoğan will almost certainly dominate national policymaking. Prime minister Ahmet Davutoğlu, who previously served as foreign minister, is a loyal Erdoğan ally, and Erdoğan has started culling other senior members of the party, leaving a chiefly pliant set of AKP officials who owe their political careers to Erdoğan.

There are three key numbers to watch:

- 330 is the number of seats Erdoğan and Davutoğlu need to push through unilateral constitutional change.

- 311 is the number of seats the AKP currently holds.

- 276 is the number of seats that constitutes a majority.

If the AKP wins 330 or more seats, it will be a surprising and astounding victory, despite a slowing economy and growing disenchantment with Erdoğan’s rule, as Constanze Letsch writes for Politico EU:

Firat Inci, a 32-year-old restaurant owner from the southeastern city of Siirt, has supported the AKP for years. This time, he intends to vote for the opposition. “The name of our ruling party is Justice and Development, isn’t it?” says Inci. “But they haven’t been able to deliver justice, and the development we have seen under this government has been nothing if not unjust.”

Over the years, the AKP has come to resemble the corrupt, authoritarian Kemalist regime it once unlodged — by the end of the last decade, prudent caution slipped into outright paranoia. Erdoğan and his allies began using the levers of government, through the Ergenekon trials, to prosecute opposition and military leaders, before turning on one-time allies, including secular allies, Islamic ‘Gulenists,’ and even top AKP figures like former president Abdullah Gül.

Despite glowing reviews for the Turkish economy, which liberalized and modernized under the AKP’s first two terms in power, corruption and rising debt have magnified the fact that Turkey’s galloping economic growth slowed to 4.1% in 2013 and to merely 2.9% in 2014.

If the AKP wins less than 276 seats, there’s a chance that Turkey’s opposition parties can form a coalition — or that the AKP will be forced to find a governing partner, the first time that Turkey will face a hung parliament since the 1999 elections.

The problem is that though Turks may be souring on Erdoğan, they are none too enamored of the other choices, either.

The chief opposition party, the Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi (CHP, the Republican People’s Party), is still discredited by its ties to governments propped up by military ‘guaranties,’ back in the era when the Turkish military appointed itself the defender of Turkish secularism. When Erdoğan first came to power in 2002, he enjoyed the support of urban liberals weary of the ‘Kemalist’ order that promised secularism, but delivered corruption, economic malaise and human rights abuses far worse than anything Erdoğan has managed (so far, at least). Its leader, and the official leader of the opposition since 2010 has been 66-year-old Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu (pictured above), a longtime accountant and official with ties to former prime minister Turgut Özal. Believe it or not, there’s just not a lot of charisma to Kılıçdaroğlu, bestowed in 1994 with the honor of ‘civil servant of the year.’

The CHP often joins forces, as it did in last August’s presidential election, with the more nationalist, right-wing Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi (MHP, Nationalist Movement Party). Together, the two parties control 177 seats in the national assembly.

It’s been a nasty campaign — Erdoğan has issued thinly veiled threats to newspapers and journalists, Kılıçdaroğlu has attacked the president for leaving behind Turkey’s poor for gold-plated toilet seats.

The most dynamic force of the election, however, has been the Halkların Demokratik Partisi (HDP, People’s Democratic Party), forged in 2012 as the union of several Kurdish and left-wing parties. Its leader, Selahattin Demirtaş, has emerged as the most compelling foil to Erdoğan, appealing to constituencies far beyond the Kurdish minority. Demirtaş has championed a higher minimum wage, educational reform and LGBT rights throughout the campaign, while pledging to block any constitutional efforts to make Turkey’s government more presidential.

Though he won just 9.8% of the vote in the August 2014 presidential election, Demirtaş must win at least 10% of the vote in this weekend’s voting, the threshold to win seats in the party-list, proportional representation-based electoral system. The irony is that Erdoğan’s government has lowered tensions between the Turkish military and the Kurdish population, relaxed limits on Kurdish culture and language and even empowered the Kurdish government that controls northern Iraq.

For all the AKP’s unpopularity, the CHP is struggling to achieve more than the 26% it won in the last election in June 2011 by appealing outside its reliable base along Turkey’s western Mediterranean coast, and the HDP might still fail to win 10% if enthusiasm doesn’t translate to votes outside its Kurdish base in the southeast.

At heart, many Turks may find little enthusiasm for any of the major parties — the AKP promise ever more Islamist authoritarianism, the CHP promises a retrograde geriatric Kemalism, the MHP an unrealistic Ottoman nationalism and the HDP a navel-gazing socialism wedded to the Kurdish movement. United, the best of the CHP, MHP and HDP might have formed a coherent challenge to the Erdoğan sultanate; fragmented, however, they will allow the AKP to aimlessly continue in power, even if they manage to block Erdoğan’s most extreme plans.