Despite headlines proclaiming a setback for Italian prime minister Matteo Renzi and his center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), Renzi’s Democrats emerge from the May 31 regional elections as the strongest national party in Italy today.![]()

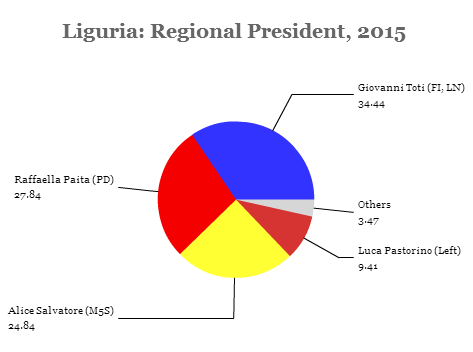

It’s true that the PD’s narrow loss in Liguria, a bellwether region straddling the Mediterranean and home to the ancient city-state of Genoa, is a disappointment for Renzi. His candidate, Raffaella Paita, narrowly lost the race to Giovanni Toti, the candidate of former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s center-right Forza Italia. Nevertheless, Renzi will be delighted to have retaken control of Campania, retained power in leftist strongholds like Marche and Tuscany and also in south-central regions like Umbria and Puglia, where the PD will govern with a much more Renzi-friendly candidate than outgoing regional president Nichi Vendola, an avowed communist.

It’s not that it was such a great election for the Democrats or for Renzi, who emerged Monday morning on a surprise visit to Italian troops in Afghanistan. There are many good reasons why voters are losing patience and enthusiasm for the youthful premier. Liberal voters worry that he has not been successful in effecting deep reforms in the face of vested interests. Leftist voters worry has is abandoning the core values of the Italian left. Voters of all stripes are despondent about the poor performance of Italy’s economy, which has only marginally improved in the past year.

Nevertheless, the alternatives to the Democratic Party are still so divided or extreme that the PD is still by far the clearest party of government. If Renzi can achieve more reforms and if the Italian economy improves over the next three years, there’s no reason to believe that Renzi won’t consolidate the PD’s gains at the next national elections, potentially transforming the Democrats into the kind of dominant party of government that the now-defunct Christian Democrats were from the 1950s to the 1990s or that Berlusconi’s center-right was in the 2000s.

Italians voted in seven of the country’s 20 regions, four of which rank among the country’s ten most populous regions. Each region holds two simultaneous elections — the first for a regional president (typically backed by a broad coalition of national and local parties) and the second for parties to the regional assembly.

Liguria, wit![]() h just 1.6 million residents, assumed overstated strategic importance as a bellwether region. The left’s loss in Liguria, after a decade in power there, had less to do with the resurgent power of Berlusconi and the centrodestra (center-right) and more to do with three confluent trends throughout the Italian regional elections, all three of which were present in Liguria.

h just 1.6 million residents, assumed overstated strategic importance as a bellwether region. The left’s loss in Liguria, after a decade in power there, had less to do with the resurgent power of Berlusconi and the centrodestra (center-right) and more to do with three confluent trends throughout the Italian regional elections, all three of which were present in Liguria.

Of movements and renegades

First, the anti-austerity Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) of Beppe Grillo continued to win anywhere from 15% to 25% of Italian voters. Despite infighting among the movement’s officials and despite the sense that the Five Star Movement never fully developed a platform much beyond grumbling about economic policy and Italy’s membership in the eurozone, Grillo’s appeal continues. That was especially true in Liguria, where the movement’s candidate, Alice Salvatore, won 24.84% of the vote, stealing support from disaffected voters on the left and the right. But the M5S outpolled Forza Italia not only in Liguria, but in every contested region except Campania — that’s hardly great news for Berlusconi and what’s left of the centrodestra.

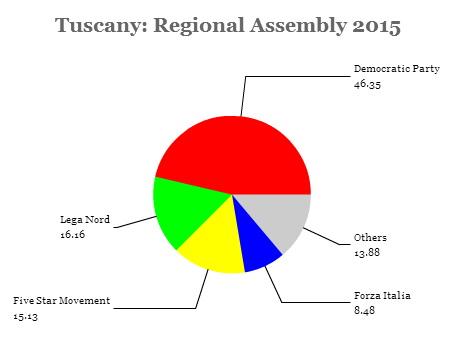

Second, buoyed by its growing strength, the Lega Nord (LN, Northern League) under the leadership of the conservative Matteo Salvini made inroads beyond its traditional base in the three regions of Veneto, Lombardy and Piedmont. The Northern League joined forces with Forza Italia to support Toti’s candidacy in Liguria, but it outpolled Forza Italia, nearly doubling its 2010 vote totals from 10.22% to 20.25% in 2015. It made a similar breakthrough in Renzi’s home region of Tuscany, where it placed second with 16.16% of the vote. Even in the south-central region of Umbria, Salvini’s Lega won 13.99% of the vote. Salvini (pictured above) has recently emphasized anti-immigration views, attacking an ‘invasion’ of migrants, and euroscepticism, attacking Italy’s membership in the eurozone. That comes at the expense of the League’s traditional call for northern Italian autonomy, but it’s a strategy that Salvini hopes will allow it to create a national base and emerge as the most important party on the Italian right. Even more than the Five Star Movement, Salvini has the potential to supplant Berlusconi as the standard-bearer of a more xenophobic Italian right.

Third and most fatal to the PD’s hopes in Liguria, the far left fielded its own candidate in Luca Pastorino, stealing votes away from Renzi’s Democrats. It’s no secret that the more strident wings of the Italian left — from labor unions to former communists — have never fully trusted Renzi. Earlier in May, Giuseppe Civati left the party, arguing that Renzi was moving it too far to the right. Indeed, if Renzi’s push for economic reform is successful, it will result in more liberalized Italian markets, which could threaten the long-term interests of unions and streamline the Italian public sector. To the extent that Renzi has so far failed to enact sweeping reforms, it’s because dissidents with the faction-riven Democratic Party have slowed or stalled the legislative process altogether. Disunity on the Italian left is a fact of life, but it’s also the factor that most endangers Renzi’s experiment.

But the narrow defeat for the Democratic Party in Liguria isn’t the only contest worth watching.

From Campania to Umbria to Tuscany: a Renzi victory

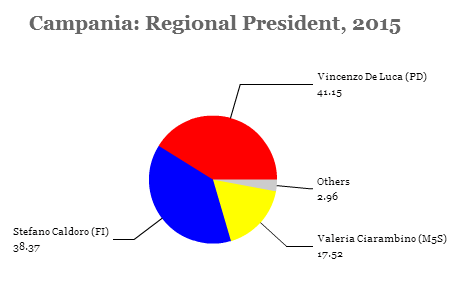

Campania, with 5.9 million residents, is h![]() ome to Naples and is the economic engine of Italy’s south, though it’s had its fair share of problems over the past decade and a half with corruption at the municipal, provincial and regional levels. The Camorra, which is based in Campania, is today the most powerful organized crime group in Italy. Power has alternated between the centrodestra and the centrosinistra (center-left) for the past two decades.

ome to Naples and is the economic engine of Italy’s south, though it’s had its fair share of problems over the past decade and a half with corruption at the municipal, provincial and regional levels. The Camorra, which is based in Campania, is today the most powerful organized crime group in Italy. Power has alternated between the centrodestra and the centrosinistra (center-left) for the past two decades.

This should be one of the sweetest victories for the Democratic Party. In fact, a parliamentary review identified Renzi’s candidate for regional president, Vincenzo De Luca (pictured above), as one of 17 candidates compromised by ties to corruption just days before the election. De Luca narrowly defeated the incumbent, Stefano Caldoro, a member of Forza Italia. De Luca, who previously served as the mayor of Salerno and led the centrosinistra to defeat in the 2010 regional elections, has a prior conviction for abuse of office in relation to his mayoral tenure. That means he may have to step down as regional president, at least temporarily. In light of Campania’s importance — it is the third-most populous region in the country and it has become a showcase for the troubles of the southern mezzogiorno — the PD’s poor vetting is embarrassing, even if Salerno’s residents generally approve of De Luca’s efforts over two decades to improve the city.

But De Luca’s victory doesn’t exactly bolster the clean sweep that Renzi’s reformist agenda intends to convey, and De Luca’s narrow 2.8% victory over Caldoro is hardly convincing.

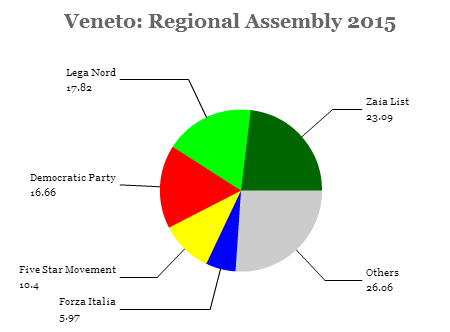

Veneto, with 4.9 million residen![]() ts, constitutes Venice and its northeastern hinterland. In contrast to Campania, the region is one of Italy’s wealthiest. Its regional president, Luca Zaia, is a popular center-right politician whose origins are with the Łiga Vèneta, a local affiliate of the autonomist Lega Nord (LN, Northern League).

ts, constitutes Venice and its northeastern hinterland. In contrast to Campania, the region is one of Italy’s wealthiest. Its regional president, Luca Zaia, is a popular center-right politician whose origins are with the Łiga Vèneta, a local affiliate of the autonomist Lega Nord (LN, Northern League).

There was never any doubt that Zaia would win reelection, if not with the landslide support of over 60% in his initial election in 2010. Notwithstanding, both Zaia in the direct presidential contest (with 50.08% of the vote) and the Lega Nord and Zaia’s personal list dominated.

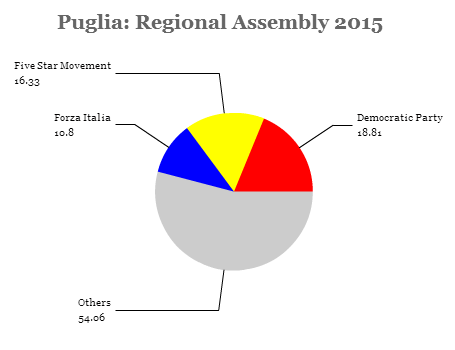

![]() Puglia, with 4.1 million residents, is another southern region, constituting the southeastern ‘heel’ of the Italian peninsula. Its outgoing regional president, Nichi Vendola, is an openly gay communist who has at times clashed with Renzi’s ‘third way’ centrism.

Puglia, with 4.1 million residents, is another southern region, constituting the southeastern ‘heel’ of the Italian peninsula. Its outgoing regional president, Nichi Vendola, is an openly gay communist who has at times clashed with Renzi’s ‘third way’ centrism.

Michele Emiliano, the former longtime mayor of Bari, easily won election with 47.12% of the vote, outpacing the Five Star Movement, a nationalist conservative candidate and the fourth-placed center-right candidate. Local parties, however, and candidate-specific ‘lists’ dominated the parliamentary vote. Though Emiliano’s allies will control the regional assembly, it’s a bad sign for the Democrats that the party polled nearly 30% less than Emiliano’s direct vote.

Tuscany, with 3.75 mi![]() llion residents, is home to Florence, the city where Renzi served as mayor before becoming prime minister in February 2013. Along with Marche and Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany is part of a wide swath of central Italy that has long supported the Italian left — even in the days when the chief opposition included the Italian communists.

llion residents, is home to Florence, the city where Renzi served as mayor before becoming prime minister in February 2013. Along with Marche and Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany is part of a wide swath of central Italy that has long supported the Italian left — even in the days when the chief opposition included the Italian communists.

It’s no surprise, then, that Enrico Rossi easily won reelection as regional president with 48.03% of the vote.