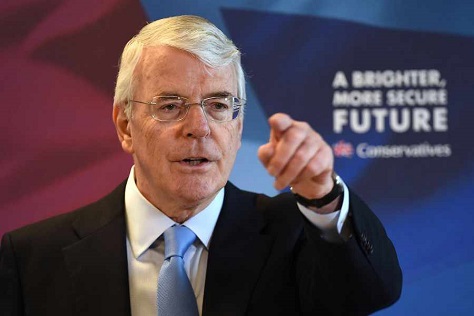

If it was surprising to see former prime minister Tony Blair two weeks ago back in the spotlight of British politics, it was even more surprising Tuesday to see his predecessor, Conservative prime minister John Major, stealing the show with just over two weeks to go until the United Kingdom’s general election.![]()

His remarks, a calculated warning about the potential rise of the Scottish National Party (SNP), which is now forecast to win nearly all of Scotland’s 59 seats to the House of Commons, show just how worried the Conservatives are about a potential coalition between the center-left Labour Party and the SNP.

* * * * *

RELATED: Scotland could easily hold the balance of power in Britain

* * * * *

With Scottish first minister Nicola Sturgeon apparently impervious to attack from Tories or from Labour in Scotland, Major delivered a rare speech on Tuesday warning that a Labour-SNP government would be a ‘clear and present danger’ to British unity, echoing in softer tones the warnings of prime minister David Cameron a few days ago, who declared a potential Labour-SNP alliance a ‘coalition of chaos.’

In typical Major style, there were few histrionics in his speech, but the only living former Conservative prime minister made it clear just how seriously the Tories are taking the joint Labour-SNP threat by warning that the SNP would ‘blackmail’ a Labour government led by Ed Miliband, pushing for small victories that will secure the SNP’s popularity prior to regional Scottish elections in 2016, en route to demands for another referendum on independence:

It is to drive a wedge between Scotland and – especially – England. They will manufacture grievance to make it more likely any future Referendum would deliver a majority for independence. They will ask for the impossible and create merry hell if it is denied. The nightmare of a broken United Kingdom has not gone away. The separation debate is not over. The SNP is determined to prise apart the United Kingdom.

With just two weeks until British voters choose their next government, there’s no sign that either the Conservatives or Labour can win a majority to govern alone. Even with the support of the Liberal Democrats, neither party is projected to win the 326 seats they will need to form a majority. With Sturgeon’s surging SNP set to win nearly all of the 59 seats in Scotland, that’s made her the potential kingmaker for the next British government.

Unlike Liberal Democratic leader Nick Clegg, who has made it clear that he could partner with either major party, Sturgeon has made it clear that she will not support a Tory government at Westminster. With little support to lose in Scotland itself, Major’s return indicates that the Conservative strategy for the next two weeks will be to scare English voters into supporting Tories with the threat of a Scottish-controlled parliament.

On the immediate merits, it’s not a bad strategy, because unless Cameron can shake up the race, the most likely outcome is that Miliband will become prime minister with the SNP’s support. It’s not inconceivable that Cameron will convince enough undecided voters and supporters of the nationalist, eurosceptic United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) to back the Tories as a way to stop Miliband and Sturgeon. To the extent that it pushes more Scottish voters toward the SNP, so much the better, because that will only deprive Labour of its once-reliable bank of Scottish seats.

If the chief message of Blair’s speech was ‘Vote Labour, or you’ll have to deal with the destabilizing effects of a referendum on EU membership,’ the chief message of Major’s speech was ‘Vote Conservative, or you’ll have to deal with the destabilizing effects of fresh demands for a new Scottish independence referendum.’

It’s a Hobson’s choice for business interests, which widely lined up behind the cross-party ‘Better Together’ campaign in the final days leading up to the Scottish referendum. Though you can expect the Tory establishment to line up against the bogeyman of a Labour-SNP government in the next two weeks, British business interests will not back Cameron with the same gusto as they backed the campaign against Scottish independence.

The irony, of course, is that Major was the last prime minister to preside over a minority government in 1996 after Labour won a by-election, forcing him to rely on the outside support of the Ulster Unionist Party to avoid a no-confidence vote.

But the Tory strategy risks alienating Scotland further from the United Kingdom in the long-run, most especially if the strategy succeeds. If Cameron, with the support of Clegg’s Liberal Democrats, Nigel Farage’s UKIP and perhaps a handful of Northern Irish parties, cobbles his way to 326, it will leave Scottish voters, once again, with no effective voice in government.

Also ironically, the prospect of SNP power at the heart of Westminster could backfire on the independence movement by proving that the British electoral system can deliver adequate representation to Scottish voters under the right circumstances. It will be much easier for Sturgeon and her predecessor, Alex Salmond, to make the case for another independence referendum if they are outside of government with little influence on British policymaking overall.