As the results started to trickle in early Wednesday morning (Jerusalem time), the world started to get a better sense of the verdict of Israeli voters in the country’s second general election in three years.![]()

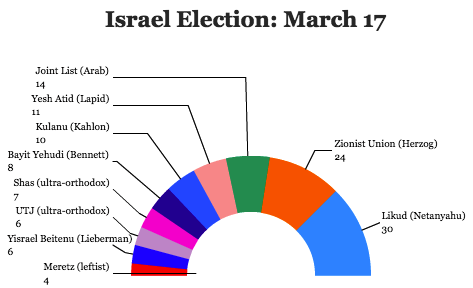

Exit polls that initially showed the two leading camps tied turned out to be wrong — the results showed that Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s center-right Likud (הַלִּכּוּד) won a bloc of 30 seats in the Knesset (הַכְּנֶסֶת), Israel’s unicameral parliament.

That’s in stark contrast to polls that showed that the Zionist Union (המחנה הציוני), a merger between Isaac Herzog‘s center-left Labor Party (מפלגת העבודה הישראלית) and a bloc of moderates led by former justice minister Tzipi Livni, would emerge as the largest party. It instead won just 24 seats.

So what do these election results tell us?

1. Netanyahu’s back. Israel could end up with an even more right-wing government than it’s had since 2013 by incorporating the ultraorthodox parties and eschewing the secular center-left. Despite a sense that voters have wearied of prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, he will be well-placed to form the next government after talks with Israel’s president Reuven Rivlin. Likud could easily form a majority if it gathers its traditional allies on the Israeli right, including Naftali Bennett’s Bayit Yehudi (הבית היהודי, ‘The Jewish Home’) and longtime foreign minister Avigdor Lieberman’s Yisrael Beiteinu (ישראל ביתנו, ‘Israel is Our Home’). Together, the three parties form a 44-seat nuclear. With the support of the two ultraorthodox parties and from the center-right Kulanu (כולנו, ‘All of Us’), Netanyahu would have a very strong majority.

2. Likud is back. If you consider that Kulanu is really just a wayward (and, ultimately, temporarily) breakoff from Likud, it was a really, really good election for Likud. Together, the two parties won 40 seats, a better showing for Likud in a generation. That’s especially true when you consider that Netanyahu pulled much of his support from right-wing voters that had migrated to either Bayit Yehudi or Yisrael Beiteinu over the past couple of election cycles. From the beginning, Netanyahu’s aggressive turns — making the controversial speech to the US congress or dramatically reversing his support for a two-state solution on election eve — were calculated to win over those voters, not centrists. It worked.

3. A ‘national unity’ government is possible. Israel could also wind up with a ‘national unity’ government that somehow incorporates the Zionist Union as Netanyahu’s junior partner, an approach that Rivlin favors, according to Israeli media. In the carousel of Knesset coalition-building, it wouldn’t be surprising at all for Labor, at least, to join forces with Netanyahu, who could use their help in repairing diplomatic ties with the United States and Europe. As recently as 2011, Labor was part of a Netanyahu-led government, and it’s not hard to think that Herzog would make a deal in exchange for the post of foreign minister and a left turn on economic policy.

4. The Labor Party may not be viable. This election was supposed to be Labor’s big comeback. But it was more like a thud and Herzog’s less than charismatic performance made it seem like the analog to the 2004 presidential election in the United States, pitting Herzog as John Kerry. But Labor’s shortfall (even with the support of a former Likudnik like Livni) raises serious questions about its future, and Herzog’s future. Labor hasn’t won an Israeli election since 1999 and, since Ehud Barak lost the premiership in 2001, it’s shuffled through seven leaders, four in the past decade alone.

5. Theoretically, there’s enough support for a Herzog-led government. If, somehow, the center holds together, and the Zionist Union convinces Kulanu to join it in power alongside former finance minister Yair Lapid’s secular centrist Yesh Atid (יש עתיד), there’s an unlikely, but possible, path to an anti-Netanyahu coalition. But it would require Kulanu’s leader, the hawkish Moshe Kahlon, a former Likud minister, to join hands with the Arab nationalist parties or, alternatively, force Lapid into government with haredi parties that he despises.

6. Israel Arabs have had a strong election. Without seeing any numbers on turnout, the ‘Joint List’ (القائمة المشتركة, הרשימה המשותפת), the united coalition of Arab parties, had a magnificent election. It means that Israeli Arabs will hold more seats than the ultraorthodox parties, in aggregate. That’s stunning, and it indicates that the drive for unity worked. Ironically, the Joint List came together only after Lieberman forced an increase in the electoral threshold from 2% to 3.25%. But it’s one thing to join forces in a three-month campaign, it’s a far different thing to maintain that unity over years, especially when the Arab camp includes socialists, communists and Islamists of all shades.

7. Yes, Kahlon’s a kingmaker. Of course, Kahlon is now in a prime position to dictate the course of coalition negotiations and demand an important role for himself and Kulanu — the immediate guesses are that Kahlon will want the finance ministry for himself or the foreign ministry for former US ambassador Michael Oren. In that regard, Kahlon is in 2015 what Lapid was in 2013. These ‘kingmaker’ moments are great for Kahlon, Lapid, Lapid’s father Tommy a decade ago, Livni and everyone else, but they only incentivize the further fragmentation of Israeli politics. In that light, Kahlon’s decision is pretty easy to make. He can take his chances in a shaky left-wing government propped up by the Arab parties, or he can join Netanyahu and, perhaps, put himself in a position to become the heir to Netanyahu in a couple years’ time.

8. Israel still has an existential choice. For all the hand-wringing over US-Israeli relations, and the damage that Netanyahu has done to Israel’s international reputation over the course of the campaign (or his premiership), it doesn’t change the fundamental question that Netanyahu, Herzog or any Israeli leader has to ask. Israel can be a Jewish state, or it can be a democracy, but it cannot be both so long as it’s still occupying Palestinian lands that are home to 4 million people without representation in the Israeli government. It’s as simple as that. Though Netanyahu, in his victory speech, tried to walk back earlier, much nastier comments on Tuesday about ‘Arab voters,’ this fundamental tension will continue to drive actors both inside Palestine, Israel and elsewhere to find a solution to the Israeli-Palestinian puzzle.