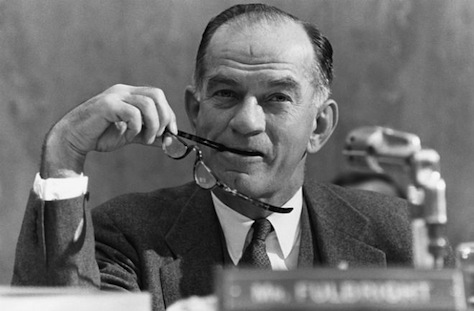

One of the great contrasts lurking underneath the latest outrage of the day in American politics is that Arkansas, the state that produced as its senator throughout the late Jim Crow era was a progressive Democratic voice and a crucial dissenting clarion on Vietnam. Fulbright, whose name is synonymous with thoughtful foreign policy in the 1960s and the 1970s, a multilateralist who helped midwife the United Nations and who stood up to the tyranny of Joseph McCarthy’s deranged anti-Communist witch hunts. He also thought the segregation of African Americans was perfectly fine, he joined the filibuster against the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and he opposed the Voting Rights Act of 1965. He served as the head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee from 1959 to 1974. He was rumored to be John Kennedy’s top choice to be secretary of state, ultimately disqualified by the his shameful support for segregation.

On Monday, Tom Cotton (pictured above), the heir to the other Arkansas seat in the United States Senate, and who won the seat as the darling of the ‘tea party’ movement on the American right, drew verbal missiles from much of the American left (and quite a few moderate Republicans) for organizing a purposefully inflammatory letter to Iran, just as US president Barack Obama and his administration enter a crucial period in negotiations over international sanctions against Iran, a country of over 77 million people, and its desire to build a nuclear energy program.

* * * * *

FROM THE ARCHIVES: As Rowhani takes power, US must now move forward to improve US-Iran relations

* * * * *

The chasm between Fulbright and Cotton is amazing. It’s a lesson in the dynamism of American politics or, really, any political system. The same jurisdiction that just 60 years ago produced a Fulbright can today produce a Cotton. The same jurisdiction than seven years ago enthusiastically supported hard-line conservative ‘principalist’ Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, with his venal anti-Semitic rhetoric, can today embrace the liberal reforms of Hassan Rowhani.

It’s also a lesson that no single political leader or official is right all of the time. Just as Fubright’s record on civil rights appears to us today as inhumane and unjust, Cotton could one day emerge as a thought leader on any number of issues. (Though probably not on Iran, if his Monday letter is any indication).

Yes, Tom Cotton’s letter is basic

No one will remember this stunt a year from now or a decade from now. It probably won’t even have much of an impact by the time March 24 arrives, the latest artificial deadline established by the ‘P5+1’ group of countries reaching for a workable deal in respect of Iran’s nuclear energy program.

Part of that has to do with the letter’s amateur-hour tone:

We hope this letter enriches your knowledge of our constitutional system and promotes mutual understanding and clarity as nuclear negotiations progress.

Get it? They used the word ‘enrich!’ As in uranium.

It has come to our attention while observing your nuclear negotiations with our government that you may not fully understand our constitutional system. Thus, we are writing to bring to your attention two features of our Constitution…

I’d wager any amount that Iranian leaders have a stronger understanding of the US political system than Cotton has of the Iranian political system. Quick, can you describe how the Iranian Assembly of Experts is elected? (Directly, believe it or not). Do you know how many seats are in the Assembly? (86). What is its most important function? (Electing the Supreme Leader and engaging in oversight).

But forget the Iranian system, Cotton and his allies even apparently got the US system wrong:

First, under our Constitution, while the president negotiates international agreements, Congress plays the significant role of ratifying them. In the case of a treaty, the Senate must ratify it by a two-thirds vote.

As Lawfare‘s Jack Goldsmith wryly noted, the US Senate doesn’t ratify treaties, it merely provides ‘advice and consent’ to the president, who ultimately ratifies the treaty. If you’re going to deliver a Schoolhouse Rock lecture to Ali Khameini, you should probably get your constitutional doctrine crystal-clear.

But does any of this matter?

Of course not. And precision doesn’t matter for a freshman senator trying to lay down a gauntlet in a contest to out-hawk the other hawks over a distorted view of Iran that’s perpetually stuck in 1979.

What we should all be talking about instead

Much more important than the silliness of the Cotton letter are dozens of questions about US-Iranian relations that are, once again, obscured by the latest outrage of the day.

For example, though Republicans, Democrats and the media alike conflate Iran’s ‘nuclear program,’ there’s a real question about whether Iran even wants to pursue nuclear weapons. Even Khamenei, the Supreme Leader himself, has issued a fatwa calling the development and use of nuclear weapons (and all weapons of mass destruction) anti-Islamic. Some US and European scholars take that fatwa more seriously or skeptically than others, of course. But a nuclear energy program is different from a nuclear weapons program, and it’s a distinction that even senior US media and officials all too often conflate. It wouldn’t be the first time the United States misinterpreted signals about Middle Eastern weapons of mass destruction.

Will the March 24 deadline even hold? At each turn, since negotiations began with the Rowhani administration, an impasse has only served as prelude to another extension. The parties agreed just an interim agreement in November 2013. The next deadline — August 25, 2014 — came and went without permanent resolution. There’s every indication, from the US congressional calendar alone, that the current target will slip. Coming just seven days after an Israeli election, it beggars belief that the P5+1 would agree a deal if, say, Isaac Herzog, the leader of the opposition Israeli Labor Party, were in the middle of coalition negotiations.

To what extent are the US and Iranian governments currently working in tandem to stop the progress of jihadist Islamic State group (الدولة الإسلامية) in Iraq? Joshua Keating was writing in Slate just last week that the United States and Iran are essentially taking turns providing air cover to the Iraqi national army in its efforts to combat ISIS/Islamic State. Bilateral relations today look less like a 21st century cold war and more like U.S.-Soviet cooperation during World War II. From Yemen to Turkey to Afghanistan, the tectonics of shifting Middle Eastern politics all favor a greater role for Iran. Metternichian realism compels no other outcome.

Democratic calls for prosecution under the Logan Act

are an insult to Congress, too

Calls to prosecute Cotton (and, presumably, the other 46 Republican senators) under the Logan Act, a possibly unconstitutional 18th century statute, are even battier than the letter itself. It’s just another example of the outrage arms race that takes place on a near-daily basis in US politics today on the professional right and the professional left.

The Logan Act, which dates from 1799, prohibits U.S. citizens “without authority” from essentially carrying on correspondence or intercourse with any foreign government. The law dates from an attempt by the Adams administration (which gave the United States such upstanding legislation as the Alien and Sedition Acts) to silence a pro-France legislator in an era when American political parties divided on foreign affairs (Adams’s Federalists were pro-British, Thomas Jefferson’s Republicans pro-French). It’s a disgraceful law from an administration that has probably the most appalling record on political speech in American history.

Republican president Ronald Reagan blustered about using the Logan Act to silence House Democrats in the late 1980s over Nicaragua, but wiser heads prevailed.

If there’s any role for a feckless opposition that doesn’t hold executive power, certainly it includes writing ill-informed missives about the real or perceived failures of presidential-led foreign policy. Even when the Democratic Party controlled the US Senate in early 2014, the body busied itself with diplomatically troublesome legislation. And why not? That’s exactly what checks and balances are about. Inarticulate as it may be, the Cotton letter embodies an alternative view of the Islamic Republic that assumes the worst at every unknowable variable. The policy debate is worth having, even if stunts like the Cotton letter ultimately debase and distort the discussion.

But at a time when the West is calcifying its disapproval of Russian president Vladimir Putin’s unilateralism, it’s an odd argument that Congressional Republicans should be somehow barred by a constitutionally suspect 18th century statute from picking a Twitter fight with Iran.

Also, as it turns out, Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif can stand up for himself.