With the world’s attention on a political assassination in Moscow, voters in the former Soviet republic of Estonia go to the polls tomorrow, March 1, with the threat of Russian aggression looming on its eastern border. ![]()

Three days ago, US troops, as part of NATO exercises, paraded in Narva, one of Estonia’s largest cities, resting on the Russian border, and Russian troops reciprocated with a similar show. Though it felt like a Cold War throwback, the demonstration highlights just how seriously Estonia, a member of NATO since 2004, and other NATO allies are taking the possibility of a Russian incursion in the Baltics.

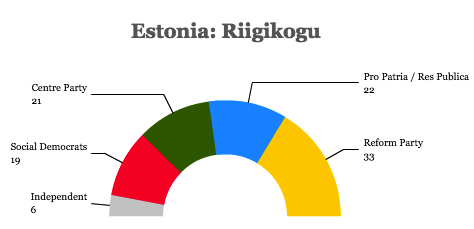

Under that tense penumbra, voters will elect all 101 members of Estonia’s parliament, the Riigikogu, where the center-right Eesti Reformierakond (Estonian Reform Party) currently controls the largest bloc of seats and governs in coalition with the centrist Sotsiaaldemokraatlik Erakond (Social Democratic Party).

Some polls show, however, that the center-left Eesti Keskerakond (Estonian Centre Party) narrowly leads the Reform Party, with the Social Democrats and the conservative opposition party, Isamaa ja Res Publica Liit (IRL, Pro Patria and Res Publica Union), trailing close by in third and fourth place.

It’s the first time that Estonia’s youthful new prime minister Taavi Rõivas (pictured above) will lead the Reform Party into an election. When longtime prime minister Andrus Ansip stepped down in March 2014 after nine years in office, the idea was that he would switch jobs with former Reform Party leader, prime minister and European commissioner Siim Kallas. That worked out for Ansip, who’s now Estonia’s representative to the European Commission with a ‘super-portfolio’ for the digital single market.

Kallas, however, was tripped up by a scandal dating to his days as Estonia’s central bank president in the 1990s, and he stepped out of consideration for the premiership. Other heavy hitters like former foreign minister Urmas Paet also demurred. That meant that the challenge fell to the 35-year-old Rõivas, whose government experience included just two years as social affairs minister. Married to pop singer Luisa Värk, Rõivas has been a member of the Estonian parliament since 2007 and is generally seen as close to Ansip.

The Centre Party’s leader, Tallinn mayor Edgar Savisaar, is nearly three decades older, and he served briefly from 1991 to 1992 as Estonia’s first independent prime minister. During the campaign, he’s made much of Rõivas’s relative inexperience.

Even if the Centre Party wins the most votes in tomorrow’s election, it doesn’t mean Savisaar will become prime minister again. Although Estonia’s well-known, social democratic president Toomas Hendrik Ilves has committed to giving the winning party the first shot at forming a government, the Centre Party’s lead will not be large enough to govern without allies — and none of Estonia’s major parties seem willing to work with Savisaar.

The reason? It all comes down to Russia.

Each of the Baltic countries — Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia — feature social democratic parties with sympathies of varying degrees for Moscow and that win much of their political support from ethnic Russian voters. That’s made the Baltic left suspicious to many ethnic non-Russians, including ethnic Estonians, and it’s one reason why so many Baltic governments in the past quarter-century have been center-right in orientation.

Savisaar (pictured above) perfectly personifies that conundrum. As mayor of Tallinn, Estonia’s capital, he has pursued wider social spending programs, free public transportation and a massive minimum wage hike as part of a broader populist platform designed to boost low- and middle-income Estonians. In the abstract, that’s a conceivably compelling policy alternative to the budget-cutting austerity that the Ansip government introduced. Like the Social Democrats (and unlike the Reform Party), Savisaar also opposes Estonia’s unique 20% flat tax and instead prefers introducing a progressive income tax.

That might be especially true today, with the country’s economy still struggling. After Estonia’s GDP growth plummeted by 14.9% in 2009, the country endured what amounts to an internal devaluation — with Estonia locked into the eurozone, wages dropped (instead of its currency) to boost export competitiveness. As it stands, the country’s struggled to reach even 2% GDP growth in 2013 and 2014,

But Savisaar’s ties to Moscow, at a time when many Estonians worry about Russian intentions in its ‘near abroad,’ complicate that message. Even as many ethnic Estonians worry that Russian president Vladimir Putin, after provocations in Georgia in 2008 and in Ukraine in 2014, might turn to the Baltics next. Estonia, where around 25% of its 1.3 million people are ethnic Russians, could be a particularly susceptible target. Though it’s the third-most populous city in Estonia, Narva’s population is 95% Russian-speaking and is surrounded by Russia to its east and south. That means it has emerged as a potential fault-line in the growing tension between Russia and Western governments. Unlike Ukraine, Estonia is a member of the European Union, the eurozone and NATO, and it conducts nearly twice as much trade with Nordic neighbors Finland and Sweden than with Russia.

Ultimately, so long as the Centre Party doesn’t completely rout the Reform Party, Rõivas (or, potentially, another top Reform figure) could govern with the Social Democrats again and, perhaps, the more conservative IRL.

Getting to a majority, however, might be more difficult after the 2015 elections than the 2011 elections. That’s because two new parties have a shot of reaching the 5% support threshold to win seats in the Estonian parliament.

The first is the more center-right, liberal Eesti Vabaerakond (Free Party), founded last September by Andres Herkel, a well-known Estonian intellectual who supported the independence movement in the 1980s and who’s also cool towards Russia. It’s easy to imagine the Free Party as a junior partner in a multi-party Reform-led coalition.

The second is the conservative Eesti Konservatiivne Rahvaerakond (EKRE, Conservative People’s Party of Estonia), founded in March 2012 as a merger between two prominent parties, one agrarian and one nationalist, resulting in a party that lies farther to the right than the IRL. It’s relatively eurosceptic, unlike the Reform Party and the Social Democrats, and its policy goals are designed expressly to defend ethnic Estonians. Needless to say, it’s not very fond of Russian posturing abroad, but it’s hard to believe that it would enter government with pro-European centrists.