Less than a year after his resignation in the wake of a strategic miscalculation, a break with India’s conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, or भारतीय जनता पार्टी) over its decision to anoint Narendra Modi, then the chief minister of Gujarat, as its prime ministerial candidate in 2014, Nitish Kumar is back as the chief minister of Bihar state.

It’s not every day that Patna, Bihar’s capital city, becomes the epicenter of Indian domestic politics. But the return of Kumar (pictured above) heralds the comeback of one of India’s most wily politicians, a potential national rival to Modi, and one of the most capable policymakers in India today. It’s no exaggeration to say that Kumar’s ‘Bihari model’ is in some ways superior to Modi’s ‘Gujarati model’ when you look at the development gains that Bihar state made under Kumar’s nearly decade-long tenure as chief minister from 2005 to 2014.

Kumar’s return comes no less than nine months before regional elections are due in Bihar, one of India’s most important states that will now be shaped widely as a standoff between Kumar and Modi.

With nearly 104 million people, it’s India’s third most populous state. Bordering Bangladesh on its far eastern corner, Bihar has a predominantly Hindi-speaking, Hindu-practicing population. But 16.5% of the population consists of practicing Muslims, making it an especially diverse state in terms of religion.

Don’t underestimate how important the state is — and how important its further development could become. Bihar is home to more people than the entire country of The Philippines or Vietnam or Egypt, and it’s only at the beginning of what could be a longer trajectory of rising economic growth.

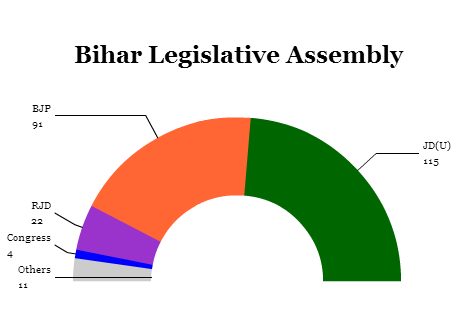

For now, Kumar is taking a gentle stand with respect to Modi, pledging to work with India’s new prime minister for Bihar’s benefit. But Kumar will not be renewing a one-time alliance between the BJP and Kumar’s own party, the Janata Dal (United) (JD(U), जनता दल (यूनाइटेड)).

Once a leading player in the BJP-dominated National Democratic Alliance (NDA), Kumar pulled the JD(U) out of its alliance with the BJP when it became clear that Modi would lead the alliance through the 2014 elections. That was a difficult proposition for Kumar, whose party attracts a significant share of votes among Bihar’s Muslim population. Modi’s reputation among Muslim Indians remains fraught, in no small part over Hindu reprisals for the burning of a train of Hindu pilgrims. Those riots, which took place in 2002 in the first months of Modi’s tenure as Gujarat’s chief minister, led to the deaths of nearly 1,000 Muslims. Critics argued that Kumar, instead, wanted to be the BJP-led alliance’s candidate in his own right, and observers point to long-standing antipathy between Modi and Kumar, as veteran writer Sankarshan Thakur writes in The Telegraph:

The two men have duelled infamously on the national stage and the prickly needle between them became the sole cause of the collapse of the JDU-BJP alliance in Bihar and the crises that have dogged the state to this day. The Modi juggernaut had decimated Nitish in the 2014 Lok Sabha polls and caused him to resign. Nitish has displayed a near-pathological aversion to Modi, refusing even to bring the Prime Minister’s name to his lip. His return as chief minister raises the charming prospect of the two men having to come face to face and engage as leader of nation and state.

Bihar’s regional elections, due before November, will be the most important political test for Modi’s strength since his election last year. The BJP’s recent loss in regional elections in the National Capital Territory of Delhi to the anti-corruption Arvind Kejriwal must certainly give Kumar hope that he, too, can unlock the means to defeating Modi. For their part, the BJP, under the leadership of former Gujarati minister Amit Shah, will pull no punches in its attempt to wrest Bihar away from Kumar, giving it a key foothold in northeastern India. If Modi and the BJP succeed in Bihar, they will have a credible shot at winning 2016’s elections in West Bengal — the fourth-most populous state in India and, like Bihar, both much more Muslim and much poorer than the rest of India.

Despite his nine-month hiatus from government, Kumar will be angling to win his fourth consecutive victory in local elections, as the JD(U) and Kumar personally remains widely popular.

But the more important point for India is that as the Nehru-Gandhi family licks its wounds after the worst electoral performance in history of India’s long-dominant Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस), there’s a space for upstart figures like Kejriwal, now Delhi’s crusading chief minister, and Kumar, the former Modi-ally-turned-opponent, to become India’s new opposition, using issues like corruption, transparency and development to displace Congress and its charmless leader, Rahul Gandhi.

Congress slipped out of power in the southern powerhouse state of Maharashtra last October, despite its strength in Mumbai (Bombay), and it has such a minor support base in Bihar that it will barely register as an afterthought in what is shaping up as a direct contest between Kumar’s JD(U) and Modi’s BJP.

Though Kumar’s decision to part ways with the BJP over Modi may have cost him politically in 2014, Kumar’s success owes in large part to his policy achievements. Bihar remains one of the poorest states in India, but Kumar’s dedication to strengthening the rule of law helped deliver some of the highest state-level growth in the entire country. With limited resources, Kumar hasn’t been in a position to revamp the state’s development agenda, but he has been able to prioritize some programs, like providing bicycles to schoolgirls that achieve a ninth-grade level of education. Kumar introduced measures to increase government transparency, and his government fines civil servants personally if they don’t deliver public services within a proscribed amount of time.

Kumar’s return to government in Bihar last week, however, wasn’t particularly smooth. After the results of the May 2014 election, in which the JD(U) lost all but two of Bihar’s seats in the lower house of India’s national parliament, Kumar promptly resigning, taking the blame for his party’s losses. By the time of the April/May 2014 elections, however, the Modi wave had become so dominant that no one seemed able to stop him, and the BJP won 22 seats, primarily in western Bihar.

* * * * *

RELATED: What does Nitish Kumar want?

* * * * *

Kumar arranged for an ally, Jitan Ram Manjhi, to succeed him as chief minister, presumably an ally willing to step aside in the future when Kumar might want to resume his old job. That’s not uncharacteristic in India, where even politicians under investigation for corruption and barred from holding office arrange for supplicant caretaker officials to rule in their place — most recently, Tamil Nadu chief minister Jayalalithaa.

The plan proved trickier for Kumar when Manjhi started veering off with erratic statements and refused to step aside, bolstered by the BJP’s sudden support for a Manhji-led government. When Kumar forced a vote in the Bihari assembly last week, however, Manjhi crumbled. Kumar now has a couple of weeks to assemble his own majority in the Bihar assembly, and he is likely to join forces with a mentor-turned-foe Laloo Prasad Yadav, the leader of the Rashtriya Janata Dal (RJD) and himself a former chief minister.

Yadav, a popular figure owing to his role as a member of the lower caste, dominated Bihari politics between 1995 and 2005, then with Kumar as his junior partner. Between 2004 and 2009, as Kumar began to eclipse him in Bihar, Yadav served as India’s railways minister in the national government between 2004 and 2009. Two years ago, however, he was convicted of corruption — a far too common fate for Indian leaders.

Bihar’s politics have, for decades, diverged from the same trends that dictate politics at India’s center. Though the abrupt attention in Patna’s direction was surprising in the past week, it certainly won’t be the last time that Indian politics looks to Bihar as a weathervane in 2015.