There are two ways of looking at Sweden’s approach to immigration policy.![]()

Under one view, the country’s generous asylum policy, with respect to Bosnia and Herzegovina in the 1990s as much as Syria today, isn’t just a human rights cause. It’s also an opportunity to buttress Sweden’s much-vaunted welfare system as birth rates decline and its population becomes older. The creation of a well-integrated, highly-skilled, prosperous and genuinely happy class of ‘New Swedes’ could one day provide a template for 21st century liberal European (and Scandinavian) values.

Under another view, the country’s increasing immigrant population is becoming ever more isolated from mainstream social and economic networks. That, in turn, has created a quasi-permanent tier of second-class immigrants without the tools or the social capital to rise to prosperity within Swedish society, and that’s weakening a welfare system already under demographic strain. At worst, it is engendering resentment among Sweden’s new immigrants and potentially, a turn to radical Islam, thereby threatening Sweden’s liberal values. Even for Syrian professionals who now live in Sweden, securing housing, employment and a sense of normalcy often prove elusive.

* * * * *

RELATED: Löfven not to blame for probable early Swedish elections

* * * * *

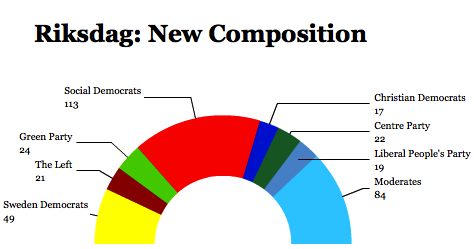

Having secured a budget deal for 2015 (and, theoretically, through 2022) between his center-left government and the center-right opposition, the four-party Alliance, Swedish prime minister Stefan Löfven will narrowly avoid a snap election in March that could have strengthened the third force of Swedish politics, the anti-immigration Sverigedemokraterna (SD, Sweden Democrats), which won 12.9% of the vote in last September’s general election and 49 seats in the Riksdag, Sweden’s unicameral parliament.

Before Löfven struck the budget deal, polls showed that the Sweden Democrats could win as much as 17.5% in fresh elections, and that’s even while its charismatic, young leader Jimmie Åkesson was still officially on leave, due to exhaustion following the September vote.

Under the terms of the deal, the so-called ‘December Agreement,’ Löfven agreed to adopt the center-right’s proposed budget for 2015, though the Alliance agreed not to reject his government’s budgets in future years. The two blocs will also cooperate on a range of issues from defense and security policy to energy policy. It pushes Sweden one step closer toward a ‘grand coalition’ government, leaving both the Sweden Democrats and the the far-left Vänsterpartiet (Left Party) in opposition to the agreement.

Crucially, the deal limits the ability of the Sweden Democrats to hold future budgets hostage in exchange for cuts to immigration quotas or other policy changes that would have left Sweden’s government permanently impaired. So long as the deal holds, it virtually eliminates the SD’s parliamentary leverage.

That doesn’t, however, mean that Löfven, who leads the Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetareparti (Swedish Social Democratic Party), or any of the four parties in the Alliance, including the liberal Moderata samlingspartiet (Moderate Party) of former prime minister Frederik Reinfeldt, can afford to avoid the issues that the Sweden Democrats are raising about the efficacy of Sweden’s immigration and asylum policy.

For a long time, both the Swedish center-right and center-left have been able to ignore the Sweden Democrats as an outlier on the far-right fringes of national politics. It’s true that the party, founded in 1988, has some fairly nasty neo-Nazi roots. Though the party’s membership still provides embarrassingly racist headlines from time to time, Åkesson and its current interim leader, Mattias Karlsson (pictured above), have undoubtedly pulled the party closer to the mainstream since 2005 and, especially, since 2010, when it first entered the Riksdag.

It’s a party that now commands the support of nearly one-eighth of the Swedish electorate and might easily soon boast the support of 20% or more. In short, it’s no longer sufficient for the center-right or the center-left to ignore the Sweden Democrats, and that’s no less true because the Swedish political elite struck a deal to avoid new elections. As Sweden’s center-right and center-left find common ground, however, it gives the Sweden Democrats an opportunity to position themselves as the ‘genuine’ opposition on immigration, EU matters and other contentious issues, while casting both the governing Red-Green coalition and the opposition Alliance as two sides of the same anti-democratic coin.

That’s all the more reason for Löfven and center-right leaders to make a convincing case that their policies can produce successful immigrants and then deliver by providing immigrants with the means to thrive economically. It’s not the case that one-eighth (or more) of the Swedish electorate are narrow-minded bigots, it’s not even that Åkesson, Karlsson or other SD leaders are racists, because they are arguably giving voice to legitimate fears that Sweden’s immigration policy is failing both Sweden and its growing immigrant class.

With a population of just 9.6 million, Sweden is set to receive up to 105,000 refugees this year alone, many of whom are seeking asylum from war-torn Syria. The country adopted a policy under Reinfeldt’s government to grant automatic asylum to any Syrian arriving in the country, making Sweden by the most welcoming European country for refugees. But it’s also been accompanied by a rise in anti-immigrant sentiment — earlier this week, an arson attack at a mosque in Eskilstuna injured five people.