As expected, Japan’s prime minister Shinzō Abe (安倍 晋三) and the governing Liberal Democratic Party of Japan (LDP, or 自由民主党, Jiyū-Minshutō) easy won snap elections called less than three weeks ago.![]()

Despite growing doubts about Japan’s precarious economy, which entered an official recession last quarter, Abe maintained a two-thirds majority in the lower house of Japan’s parliament. The most amazing fact of the election is that Japan’s opposition parties, despite a feeble effort against Abe’s push for reelection, lost virtually no ground.

* * * * *

RELATED: Abe calls snap elections in Japan as recession returns

* * * * *

Nevertheless, it’s hard not to conclude from the results and the sudden December election campaign that Japan today has essentially returned to one-party rule for the time being. It puts a grim end to a period that began in 1993 with the first non-LDP government in over 40 years, and that culminated with the clear mandate of the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ, or 民主党, Minshutō) in the 2009 general election. The DPJ cycled through three different prime ministers in three years, and it often appeared to stumble in its efforts to respond to the global financial crisis, longstanding declines in demographic and economic trends and the 2011 meltdown of the Fukushima nuclear reactor.

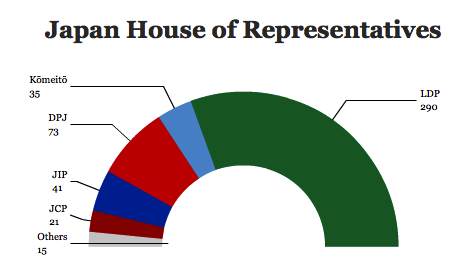

By December 2012, with promises of a massive new wave of monetary and fiscal stimulus, Abe (pictured above) swept the DPJ out of office, wining a two-thirds majority in conjunction with its junior coalition partner, the Buddhist, conservative and generally more pacifist Kōmeitō (公明党). That coalition, which controlled 326 seats in the House of Representatives, the lower house of Japan’s parliament, the Diet (国会), will now control 325 seats after Sunday’s election.

After its defeat in 2012, the Democratic Party elected Banri Kaieda (海江田 万里) as its new leader, essentially its fourth party head in four years. Kaieda, however, presented as an uninspiring choice for leader and he never seemed to grasp just how much rebuilding would be required in the aftermath of the party’s wipeout. Kaieda lost his own Tokyo constituency on Sunday, and will step down as party leader. But with just 198 candidates contesting the 325 seats elected directly, the DPJ was unprepared to wage a credible campaign to retake the Japanese government.

Former prime minister Naoto Kan (菅 直人), who presided over the government’s response to the Fukushima meltdown and who has become one of the leading anti-nuclear politicians in Japan, lost his own constituency in Tokyo and literally won the chamber’s 475th seat from among the additional 80 seats. In light of the party’s continued unpopularity, internal disunity and funding difficulties, it’s astonishing that the DPJ actually increased it number of seats from 62 to 73, which makes the 2014 election the party’s second-worst showing since the DPJ formed in 1998.

Photo credit to Haruyoshi Yamaguchi/Bloomberg.

Photo credit to Haruyoshi Yamaguchi/Bloomberg.

Yukio Edano (枝野 幸男), currently the secretary-general of the party, and the former chief cabinet secretary and the economy and trade minister, will be the frontrunner to become the next Democratic Party leader. Edano (pictured above) is best known for his role as the key contact of the government efforts to respond to the Fukushima earthquake and tsunami.

The result leaves Abe with a two-thirds majority, allowing him to override opposition in the upper house of the Diet, the House of Councillors, where its majority is much smaller, despite a resounding win in the August 2013 upper-house elections. It will largely lift Abe to an easy win in the LDP’s leadership vote, scheduled for next September. It will also win a reprieve for Abe to delay the onset of the second planned rise in the consumption tax, a measure that the prior DPJ-led government enacted to attempt to bring down Japan’s public debt, today nearly 240% of GDP. With a slug of fiscal stimulus after his election in December 2012, the heart of ‘Abenomics’ today is the widespread monetary stimulus by the Bank of Japan and its Abe-backed president, Haruhiko Kuroda (黒田 東彦).

Nevertheless, there’s no assurance that Abe will be any more successful than he has in the past two years in enacting the structural reforms that were supposed to amount to the ‘third arrow’ of Abenomics — any number of potential policy changes that could include deregulation, the privatization of water and electricity utilities, labor market reform or corporate governance reform. So far, factions within the LDP (itself just as divided internally as the DPJ) have blocked those reforms. It’s not clear how the renewed mandate will necessarily clear the pathway to a sudden burst of new legislation.

In the meanwhile, Abe has brought Japan into the negotiations for the Trans Pacific Partnership, a US-backed effort at a three-continent free-trade pact. With his reelection secured, Abe also hopes that the delay in the consumption tax increase will give the economy some breathing space to return to the kind of GDP growth that Abe seemed to induce with his reflationary policies in 2013. In the meanwhile, the Japanese yen is at a seven-year low, boosting exports and corporate profits, even as Japan struggles with a recession. It will also boost Abe’s efforts to reboot the country’s nuclear industry and force changes to give Japan’s self-defense forces more power to take a role in regional peacekeeping — two policy efforts that are widely controversial.

Nevertheless, the various third forces of Japanese politics, just as unprepared for snap elections as the DPJ, failed to make any breakthroughs either.

Osaka mayor Tōru Hashimoto (橋下徹), having abandoned an alliance with former nationalist, right-wing Tokyo mayor Shintaro Ishihara (石原慎太郎), held onto virtually all of its seats of his Japan Innovation Party (維新の党 Ishin no Tō), retaining 41 of 42 MPs, largely on the basis of the strength of its proportional representational vote. Nevertheless, Hashimoto (pictured above) conceded that the election was a defeat for a party that he hoped would one day compete with the LDP.

Ishihara, leading his newly formed Party for Future Generations (PFG, 次世代の党 Jisedai No Tou), was set to lose his seat and the PFG set to win just two seats in total. Another promising former third-party leader, Yoshimi Watanabe, who formed Your Party (みんなの党) in 2009 as a center-right party that called for the widespread quantitative easing for years before Abe’s government endorsed the approach in 2012. Your Party collapsed in November 2014 as Watanabe faced a party spending scandal.

The Japanese Communist Party (JCP, 日本共産党, Nihon Kyōsan-tō), however, won more seats (21) than at any time since 1996, largely on the strength of its criticism of the LDP’s economic policies and their failure to deliver tangible gains to middle-class Japanese in terms of income growth or greater prosperity.

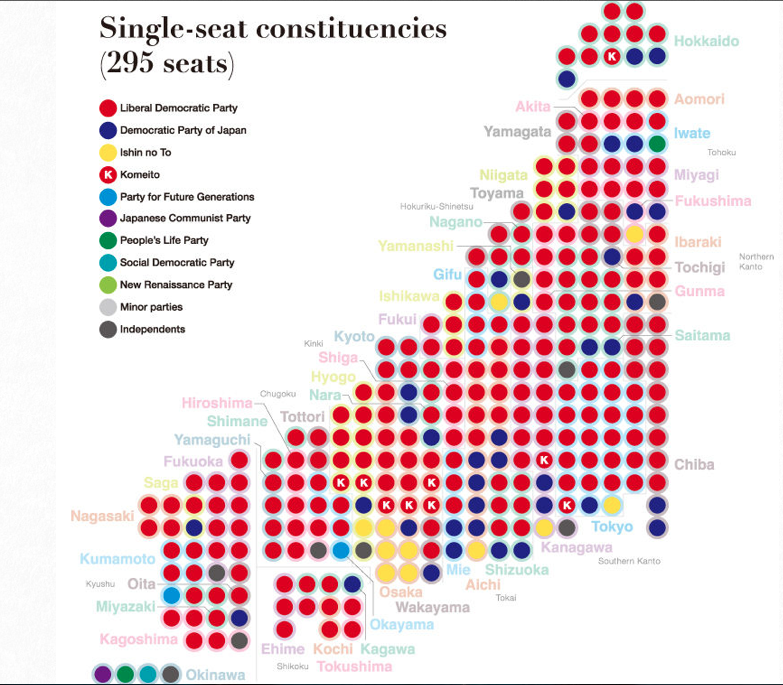

The LDP’s victory was virtually nationwide, though the Communists did particularly well in Tokyo, Hashimoto’s Japan Innovation Party did particularly well in Osaka, and the LDP lost all of its seats in Okinawa, due to local wrath over the continued presence of a US military base there.

Koizumi resigned on September 26 and was later replaced by Abe. Public support for him dropped after several scandals that began at the end of the same year. Four ministers in his cabinet were forced to resign and another, the minister of agriculture, committed suicide in May 2007 due to a financial scandal. On Sept. 12, 2007, Abe announced that he would resign from his position as prime minister because he considered that the new prime minister was needed to continue Japan’s support for US military operations

sewamobilsurabaya

rentalmobilsurabaya