Photo credit to adrianhancu / 123RF.

Photo credit to adrianhancu / 123RF.

By just about any measure, Moldova’s first quarter-century as an independent state has been inauspicious long before last weekend’s parliamentary elections.![]()

Emerging from the Soviet Union as a new state engaged in a war with separatists in Transnistria, Moldova is today the poorest country on continental Europe, and successive governments have left the country with antiquated and corrupt institutions that culminated in widespread protests (pictured above) and a political crisis in 2009. In 2014, no country in the former Soviet Union, including Ukraine, is perhaps more at risk from Russian aggression.

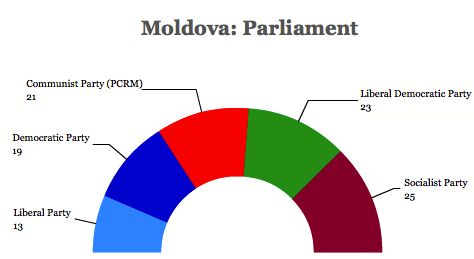

Though a coalition of three relatively pro-European parties appear to be moving forward to form a governing coalition, the winner in last Sunday’s vote was the Partidul Socialiştilor din Republica Moldova (PSRM, Party of Socialists of the Republic of Moldova), formed in 1997 and a fringe party until it received an endorsement from Russian president Vladimir Putin. The Socialists will enter Moldova’s 101-member Parlamentul (parliament), with 25 seats, the largest of five parties in the chamber.

The Socialists benefitted chiefly from a decision on November 29 by Moldova’s supreme court of justice to uphold a lower court’s decision two days earlier to disqualify the pro-Russia ‘Homeland’ Party after it was found to have accepted foreign resources.

They also gained from disenchantment with the Partidul Comuniştilor din Republica Moldova (PCRM, Party of Communists of the Republic of Moldova), which controlled Moldova’s government between 2001 and 2009. Though it’s the successor to the same Communist Party that governed in Soviet times, it became something of a populist, even conservative, party under the leadership of Vladimir Voronin, who was also elected Moldova’s president in 2001. Under Communist rule, Moldova privatized several public companies and moved toward greater EU integration, though Voronin, sympathetic to Russia, often played Brussels against Moscow. The PCRM was the election’s biggest loser, dropping from 38 to 21 seats.

Putin’s support for the Socialists mean that the party’s leader, Igor Dodon (pictured above), a former economy minister under the previous Communist government, is now indebted to the Kremlin for his position as opposition leader.

Though Moldova isn’t likely to have a pro-Kremlin government anytime soon, it’s hard to be incredibly optimistic about the three parties that will form the government, each of which functions less like a nominally center-left or center-right political party and more like the fiefdoms of government chieftains who dispense government favors and jobs and otherwise add to the country’s abysmal culture of corruption.

It comes at a time when Putin is flexing Russia’s muscle in its ‘near-abroad,’ and tiny Moldova could be an incredibly easy target for Putin’s geostrategic machinations. With a GDP per capita of around $2,200, it’s even poorer than its larger neighbor Ukraine, and far poorer than even the former Soviet state of Belarus, which still features an authoritarian government. Russia’s decision to ban Moldova’s exports last year, including its wine, hasn’t helped matters. Like Ukraine, Moldova is highly dependent on Russia for energy, including the natural gas its citizens need to heat their homes in the wintertime.

Better still from the Kremlin’s viewpoint, Moldova is not a member of NATO and, presumably, Russian interference won’t trigger the ‘Article 5‘ self-defense provisions in Moldova as in the Baltic states. That’s even though countries like Latvia and Estonia have a far higher proportion of ethnic Russians than Moldova (around 5.8% of Moldova’s population identifies as Russian).

But Russia can nevertheless find ample opportunity for mischief-making in two regions with separatist movements — Transnistria, a narrow strip that parallels the Dniester River and Moldova’s eastern border with Ukraine; and Gagauzia, four separate enclaves in southeast Moldova.

Map credit to Reconsidering Russia.

Map credit to Reconsidering Russia.

So what should Moldova do? One answer is to merge with Romania. After all, Moldovans speak Romanian and ethnic ‘Moldovans’ share much in common with Romanians. While Romania is itself among the poorest EU countries, its GDP per capita is as much as four times that of Moldova.

Romania’s outgoing president Traian Băsescu is a longtime advocate of greater union with Moldova and, especially since Romania’s accession to the European Union in 2007, many Moldovans have sought dual Romanian citizenship, which entitles them to passports that allow them to travel and work throughout the European Union. According to the Soros Foundation, at least 400,000 Moldovans have currently availed themselves of Romanian citizenship, a step that Romanian authorities are delighted to take. With a population of just 3.55 million people, that means at least 11% of Moldovans already have Romanian citizenship, and many more Moldovans are currently eligible to do so.

With so many Moldovans already entering the European Union through the back door of Romanian citizenship, it’s not surprising that its current and likely future government is committed to eventual EU membership. Moldova’s economic and political institutions have a long way to go before it could easily become an EU member, though. The EU only opened a permanent mission in Chişinău in 2005, and Moldova signed an EU association agreement only in June 2014.

One way to accelerate the process, though, is for Moldova simply to rejoin Romania. The problem is that unionism isn’t today incredibly popular among Moldovans themselves. Despite their ties to Romanians, time and history have created a space for a separate Moldovan identity to emerge. Self-determination is a powerful force, for Moldovans vis-a-vis Romania as much as for Transnistria and Gaguzia or for Catalunya or Scotland.

But though Moldovans aren’t incredibly keen today on returning to the Romanian fold, neither are they particularly keen on holding onto Transnistria at all costs. If anything, the region is an economic and political drain on Chişinău. Any merger between Moldova and Romania would almost certainly force the Transnistria issue to its breaking point. Anyone who supports a Romanian-Moldovan merger would have to be reasonably comfortable with the idea of handing maximum autonomy to Gagauz-majority regions and, quite possibly, allowing Russia to re-absorb Transnistria.

That result, unacceptable as it might be to European and US officials, might actually make the most sense historically. To understand the nature of the Moldova’s situation today, it’s helpful to understand the history of its regional relations.

For centuries, Moldavia was an independent principality. In 1812, Moldavia was ceded to the Russian Empire. In 1859, it merged with Wallachia to form the basis of modern Romania. Through the rest of the 19th century and World War I, Moldavia swung back and forth between Romania and Russia (later, the Soviet Union). In 1940, most of what is today’s Moldova was formed when Soviet leader Josef Stalin essentially usurped Bessarabia from Romania, joined it with what is today the Transnistria region, and created the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic.

In 1991, when the Soviet Union imploded, Moldova quickly declared independence and Romania, recently emerging from under the thumb of the repressive, Soviet-backed Ceaușescu regime, was the first country to recognize Moldova. If it hadn’t been for Transnistria and the ethnic Gagauz people, a Turkic group, Moldova might have simply rejoined Romania. As it turned out, autonomy within an independent Moldova didn’t satisfy the residents of Transnistria, and Moldova spent its first two years fighting a civil war against the breakaway republic of Transnistria.

Both regions today, however, are sympathetic to Russia. Though the Gaguaz aren’t agitating for independence, they remain wary about the Moldovan government’s pro-EU posture and stridently oppose any merger with Bucharest. Separatists in Transnistria, however, are quite open about their desire to return to Russian control, and Russian troops currently occupy the region as a ‘peacekeeping’ force, thereby giving Putin a position to launch future mischief throughout Moldova.

If Putin decides to annex Transnistria, where residents look to Russia for inspiration (and, increasingly, for employment opportunities), it wouldn’t be hard. Russia’s annexation of Crimea earlier this year provides a fine precedent. Demographically, Romanians, Russians and Ukrainians each comprise about a third of the population. That gives the region’s Slavic population a two-to-one majority. Russian, not Romanian, is the predominant language.

Though Putin may find that Transnistria, on its own, is too poor to be of any real value to Russia, he could use it as a staging ground for an attack on southwestern Ukraine in the pursuit of stripping away a zone of Russian influence from Transnistria all the way to Donetsk and Luhansk oblasts in eastern Ukraine, providing a convenient land bridge to the Crimean peninsula.

For now, Moldova will plod toward EU membership, in platitudes and aspirations if not necessarily in the hard work of combatting corruption and incorporating reforms to being Moldovan laws up to par with EU standards. For now, that puts the pro-Europe Partidul Liberal Democrat din Moldova (PLDM, Liberal Democratic Party of Moldova), its leader Vlad Filat and Iurie Leancă, the pro-Europe prime minister since April 2013, in the driver’s seat in the next government, even though it lost nine seats in last weekend’s voting. Though Leancă (pictured above), a former minister of foreign affairs and EU integration, has earned the respect of many Western governments, he became prime minister only after Filat was ousted in early 2013 in relation to corruption charges.

Its partner will be the Partidul Democrat din Moldova (PDM, Democratic Party of Moldova), a nominally center-left party led by Marian Lupu, a former acting president, as well as the nominally center-right Partidul Liberal (Liberal Party) of Mihai Ghimpu, another former acting president, and Dorin Chirtoacă, Ghimpu’s nephew and the mayor of Moldova’s capital, Chișinău.

William Francis McKelvey Jr. contributed to this post.