If you lose a budget vote three years into your mandate, the problem’s probably with you.![]()

If you lose a budget vote on the two-month anniversary of taking office, and less than three months after winning a general election, the problem’s probably not.

So it goes in Sweden, where voters will head to the polls on March 22 after the government lost a tough budget vote.

It wasn’t entirely unpredictable that prime minister Stefan Löfven (pictured above with Hillary Clinton) would fail to pass his first budget because of the odd dynamics of Swedish politics after September’s general election, which broke the Riksdag, Sweden’s unicameral parliament, into three blocs:

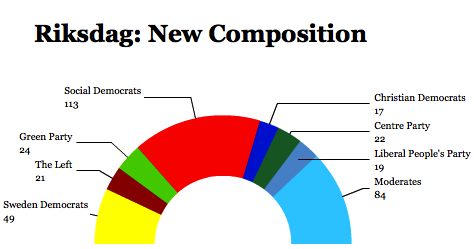

- the center-left ‘Red Green coalition,’ which includes Löfven’s Sveriges socialdemokratiska arbetareparti (Swedish Social Democratic Party), the largest party in Sweden, and its junior governing partner, the Miljöpartiet (Green Party). A third party, the far-left Vänsterpartiet (Left Party), didn’t formally join the government, but had indicated its willingness to back Löfven.

- the center-right Alliance, which includes the four parties that formed Sweden’s government for eight years until the September election: the Moderata samlingspartiet (Moderate Party) of former prime minister Frederik Reinfeldt, the liberal, urban-based Folkpartiet liberalerna (Liberal People’s Party), the libertarian, rural-based Centerpartiet (Centre Party) and the more rural-based Kristdemokraterna (Christian Democrats). The Alliance’s unity, traditionally, has given the center-right greater strength over the decades.

- the anti-immigration, far-right Sverigedemokraterna (SD, Sweden Democrats), which are deemed untouchable by either the center-left or the center-right, but which doubled its representation after September’s election, when it won 49 seats and nearly 13% of the vote.

On a rare day of parliamentary suspense in Stockholm, nearly everyone was blaming someone else for the sudden turn in events.

The Sweden Democrats, who were most immediately responsible for the failure to pass a budget, blamed the political mainstream for ignoring their concerns about rising immigration and its costs to the Swedish citizenry, the chief reason that the party cited in its decision to break parliamentary tradition and oppose the government’s budget.

Nearly 100,000 refugees are expected to come to Sweden in 2014, a wave larger than tens of thousands of Bosnian refugees that arrived in the country in the mid-1990s. Both Löfven and Reinfeldt have vigorously defended Sweden’s liberal immigration laws and the Swedish government position to offer asylum to all refugees from the Syrian war. The Sweden Democrats, who have neo-Nazi roots but are today a standard right-wing alternative akin to France’s Front national, disagree, and argue that the influx of Syrian refugees pose a threat to Sweden’s internal security and impose a burden on the country’s social welfare programs.

Several of the center-right parties, all of which opposed the government, blamed Löfven for failing to compromise. Löfven refused to abandon the Greens during aborted negotiations with some of the center-right parties in the days leading up to the budget vote. After the election, many commentators thought that the most stable government would have included the Social Democrats, the Greens, and two of the more liberal of the Alliance parties, such as the Centre Party and the Liberal People’s Party. That, of course, never happened.

Löfven blamed the government’s fall on the irresponsibility of the Sweden Democrats and, in no small measure, the lack of political imagination among the four center-right Alliance parties for putting politics above national duty.

Wherever the truth lies, the reality is that Sweden will now face its first early elections since 1958, ushering in a new period of greater political instability in a country typically known for consensus, most especially in regard of its cherished, Scandinavian welfare state.

Due to the requirement that a government must sit for three months before the Riksdag can be dissolved, there’s a small chance that Löfven can peel away support from one or two Alliance parties before December 29, when snap elections will officially be called. That could make Löfven’s announcement a dramatic gambit designed to force some of the center-right parties to the negotiating table. For now, however, Sweden is preparing for a spring election campaign.

* * * * *

RELATED: Swedish far-right could hold balance of power

RELATED: Swedish election results: Löfven’s dream liberal-left coalition

* * * * *

But there is a sense that Löfven isn’t too upset about the opportunity for a do-over of the election. This time around, neither Reinfeldt or former finance minster Anders Borg will be around to lead the party. In fact, the Moderates, by far the largest party of the center-right, were not scheduled to elect a new leader until March 2015. That’s been moved up to January. The party’s parliamentary floor leader, Anna Kinberg Batra (pictured above), will serve as interim leader and likely win the permanent leadership as well.

Meanwhile, the charismatic leader of the Sweden Democrats, Jimmie Åkesson, is on extended leave after a diagnosis of chronic fatigue syndrome. His temporary replacement, Mattias Karlsson, is a longtime SD operative who has helped shaped the party’s platform for the past three election cycles.

Löfven, however, shouldn’t be overconfident. The Centre Party’s leader, Annie Lööf, a former minister of enterprise, has been unsparing in her criticism of the prime minister, a former metalworkers union leader. If Lööf becomes the de facto head of the opposition, she might end up as prime minister by the end of March.

A Sentio poll, dated December 2, gives the Social Democrats just 27.4% of the vote, down from the 31% the party won in the September 2014 elections. While the Red-Green coalition still holds a small lead over the Alliance, the Sweden Democrats ominously garner 16.4% support. Other polls in recent weeks show support at levels relatively close to the September election outcome.

As voters decide who to blame for the atypical scenario of two election cycles in seven months, however, support could prove incredibly fluid between now and March 22.