Guest post by Christopher Skutnik

Photo credit to NTX.

Photo credit to NTX.

When he was elected in July 2012 in a relative landslide, Enrique Peña Nieto thought his administration would be defined by good governance and economic, tax and energy reforms.![]()

Above all, everyone thought that Peña Nieto would be eager to demonstrate the new look of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI, Institutional Revolutionary Party), which controlled Mexico’s presidency between 1929 and 2000, with the rise of a younger generation of technocratic cabinet members, including Luis Videgaray, EPN’s finance minister.

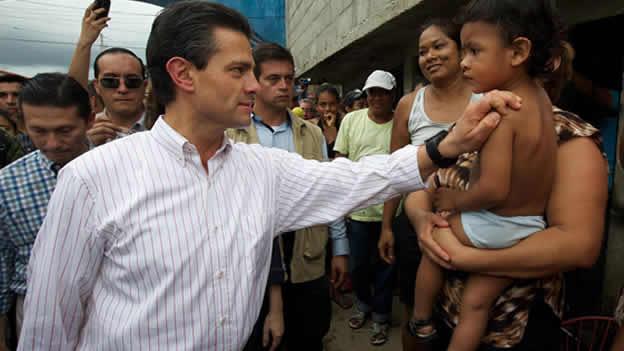

On the second anniversary of his inauguration, however, Peña Nieto (pictured above visiting Guerrero in 2013) faces the risk of losing the narrative of his presidency with four years left in office — following the September killings of 43 university students, reminiscent of the 1968 Tlatelolco massacre that is widely seen as one of the lowest points of the PRI’s 20th century rule.

So what happened in Iguala?

It’s no understatement to say that Mexicans everywhere have been touched by the incredible display of violence and governmental corruption that took place on September 26, when 43 students were abducted and, allegedly, assassinated in the town of Cocula, near Iguala, the third-largest city in Guerrero state.

The office of Mexican attorney general Jesus Murillo Karam has determined that Iguala mayor José Luis Abarca ordered local police to confront the students, since he was worried that they would disrupt an important political event at which his wife, Maria de los Angeles Pineda, was scheduled to speak.

With what appears to the approval of Iguala police chief Felipe Flores Velásquez, local officers apparently ambushed the students, (killing 6 outright), and abducted 43 more. A further 14 students successfully escaped, and were later located safely.

According to officials, Cocula’s police chief, Cesar Nava Gonzalez, ordered police to transfer the 43 captives to a local gang called Guerreros Unidos, to which Nava Gonzalez apparently belonged. The gang members then allegedly transported the students to a landfill, murdered them, burned their bodies, and dumped their remains in a local river.

The sad tale, however, becomes even more ridiculous upon further review. Los Angeles Pineda, the mayor’s wife, is allegedly known as ‘Lady Iguala’ and, along with her two brothers (both of whom were assassinated by rival gangs) was tightly connected to the Guerreros Unidos gang. Circumstantially, it appears that she used her position to leverage a considerable amount of wealth, as well as intervene on behalf of her gang.

On 28 September, Flores Velásquez, surrendered the weapons, log shifts, police vehicles, and names of those officers responsible for the massacre to the Ministry of Public Security. Strangely enough, a few days after the submission he simply disappeared, and remains a fugitive.

On 30 September Luis Abarca, his wife and their children fled Iguala to Mexico City, where they were located and apprehended a month later.

Why were the students such a perceived threat?

The students were traveling to Iguala to collect money to ‘fund forthcoming protests against what [the students] say are discriminatory hiring practices for teachers that [favor] urban students over rural ones.’ They were also collecting money to cover expenses for a delegation to travel to Mexico City to participate in an annual march, which was to commemorate the 1968 Tlatelolco Massacre.

Details diverge about how the students left their protest – surviving students say they that they tried to hitchhike back, but local officials insist that the students commandeered three local buses for their travel. Officials point to the instructions of the ‘transport committee’ at their school, the Raul Isidro Burgos Normal Rural School in Ayotzinapa. Raul Isidro Burgos purportedly nurtures a marked leftist ideology, (proudly calling itself a ‘cradle of revolutionaries’), and its transport committee periodically encourages the acquisition of public or private buses to transport the students to nearby cities or events to petition for donations. In fact, it appears that the school is rather successful to those ends – local police are known to stand by, rather than confront, the ‘commandeering’ students.

These students are in good company. Raul Isidro Burgos is one of 16 like-minded normal rural schools in Mexico, and these schools, although often geographically remote and quite frequently destitute, have deep ideological pedigrees: many of them were established after the successful Mexican Revolution of 1910, and their halls are often adorned with images of Karl Marx, Che Guevera, and even revolutionary alumni like Lucio Cabanas and Genaro Vazquez. [1]

The reaction across Mexico

While identification of the remains has not yet been indisputably linked to the missing 43, the deafening silence from many government officials and the obvious lack of certainty has supercharged an already irate Mexican populace and produced a backlash that has enveloped the country in widespread (and growing) protests.

Although ex-mayor Luis Abarca (pictured above) and his wife have been captured, the incident has electrified the nation and swung the scope of focus from Iguala to the national government itself.

Thousands of protesters have participated in marches, publicly mocked the government online and off, and one group even set fire to the doors of the National Palace in the capital of Mexico City. Others have attacked Guerrero’s government headquarters in protest of what they charged was an irresponsible and inept handling of the case.

Ángel Aguirre Rivero, the governor of Guerrero state, finally resigned on October 23. Though he was a member of the leftist opposition Partido de la Revolución Democrática (PRD, Party of the Democratic Revolution), but for decades, right up until the 2010 state gubernatorial election, he was a card-carrying member and deputy from the PRI. Many protesters have called for the resignations of Murillo and Peña Nieto.

Critics, in particular, strongly denounced Peña Nieto for traveling to Beijing earlier this month for a planned economic conference despite his homeland’s unrest, and for having yet produced no satisfying answers or actions regarding the students’ whereabouts. The scandal of the ‘missing 43’ has overshadowed another existing ethics debacle involving his wife’s dubious acquisition of a luxury home, potentially as long ago as 2012, in exchange for the awarding of an uncontested railway bid.

Mexico: corrupt as ever?

It is a cruel twist of fate that the kidnapped students were attempting to gather resources to commemorate 1968’s Tlatelolco massacre, which involved the government-sanctioned murder of between 30 and 300 students and civilians by police and military. No matter what the ultimate justification of the culprits behind September’s kidnappings (and likely murders) may be, they perfectly exemplify the widespread corruption that plagues Mexico on so many levels.

In most cases, this corruption revolves around the rampant drug-related gang violence that has consumed much of the energy of Mexican state and local governments in recent years, including the states of Juarez, Sinaloa, Michoacán, Veracruz, Zacatecas, to name a few. In many cases, local officials turn a blind eye to cartel activities, often by allowing the transport of known illegal substances to continue unabated in exchange for money.

Since former president Felipe Calderón, of the conservative Partido Acción Nacional (PAN, National Action Party) escalated the Mexican military’s drug war in 2006, over 106,000 people have died as a result, while as many as 1.6 million people have become displaced (as of 2012 alone).

Both the current and past administrations (Peña Nieto, Calderon and the PAN’s Vicente Fox, respectively) emphasized in their campaign platforms the widespread influence and violence caused by gangs. Their impact seems to have been minimally successful, at best. In fact, as the PRI’s one-party state crumbled and Mexico transitioned to a multi-party democracy, the violence seemed to worsen as drug cartels supplanted the PRI’s legitimacy in states and cities by force.

Peña Nieto came to power with the notion that he could strike a truce of sorts with cartels. The PRI, back in power, would turn a blind eye to corruption and drug cartel (within limits) if cartels reduce the violence that’s destabilized so much of the country. For whatever reason, that simply hasn’t happened. The PRI in 2014 is a shell of what it was just two decades earlier. It may be that no single party today could effect such a ‘deal.’

What does this mean for Mexico going forward?

So what does all of this unrest translate to?

Mexico has faced a local, low-scale but intense and emotionally gripping drug war for the last eight years, waged by three presidential administrations that have been unable to stem the tide of violence against innocent civilians. That, in turn, has amplified the lack of confidence in law enforcement. It’s now well known that police and military officials share widespread culpability in everything from drug trafficking to inter-cartel warfare. Notably, the catalyst for the latest violence, seems to be a corrupt local official with connections to a local cartel.

Everything about this tragedy — the corruption, the drug violence, the role of the cartels, the ineffective response of government at all levels, starting with the Peña Nieto administration — exemplifies the frustrations of millions of Mexicans about their country. Incredibly, the social unrest continues even while the Mexican economy’s outlook is rising, due in part to Peña Nieto’s energy, telecommunications and other reforms. By the end of the decade, Mexico could outpace Brazil to become Latin America’s largest economy.

But that matters little to everyday voters, many of whom have not shared in the Mexican economic boom, and who are left vulnerable to the day-to-day threat of drug-related violence. Workers nationwide, for example, called for a general strike on November 19, with many protesters chanting ‘he will fall, he will fall, Peña Nieto will fall.’

It is doubtful that Peña Nieto will be swept from office in some sort of national ‘Mexican Spring’ movement — the #YoSoy132 social protest movement didn’t disrupt his inauguration or reform plans in 2012 and 2013. But it’s not certain. At a press conference earlier this month, Murillo muttered, ‘ya me cansé‘ (‘I’m sick of this already.’). That, in turn, has become a Twitter hashtag #YaMeCansé of solidarity against the government’s callous response to the Iguala massacre. Though Mexican voters seem to place plenty of blame on the PRD and PAN as well, the attitude effected by both Murillo and Peña Nieto could lead to a disastrous result in next July’s congressional midterm elections.

Although the students have yet to be found, the local mayor and his wife, several of Iguala’s officers, and the Cocula police chief have all been arrested. It remains to be seen whether those arrests will placate a country whose citizens seem universally cansé of corruption, wanton murder, and the drug cartels and gangs that are always involved.

Christopher Skutnik is an Academic Staff Member at the Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He received his MA in International Relations from Northeastern University.

[1] Cabanas and Vazquez were both gunned down by police in the late 1960s.