In Botswana, diamonds may not be forever, but its newly reelected president Ian Khama may hope that the Khama family is nonetheless forever– and he is facing severe parliamentary and judicial pushback.![]()

Fresh off an election campaign that was fiercely contested, at least by the standards of south-central Africa, Khama is already making waves by attempting to install his brother Tshekedi Khama as vice president, clearing the way for him to win the presidency in 2018, when the term-limited incumbent will not be able to run.

Khama’s Botswana Democratic Party (BDP), has controlled the country since its independence in 1966, and his father, Seretse Khama, founded the BDP in 1961 and served as Botswana’s first president until his death in 1980. Khama, who served as vice president between 1998 and 2008, when former president Festus Mogae stepped down, comes from a powerful royal family among the Twsana ethnic group, to which 80% of Botswana’s population belongs.

By just about every standard, Botswana — a country of just over 2 million people — is one of sub-Saharan Africa’s success stories. It’s a country where elections are generally free and fair, and where good governance is a reality, not just an aspiration.

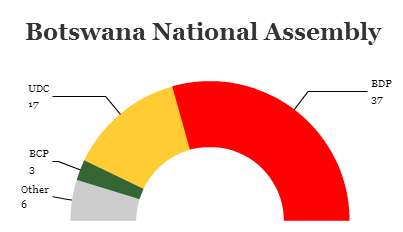

The BDP, for the first time since independence, won less than 50% of the vote, for example, in the most recent October 24 general election, though it continues to hold a governing majority in the 63-member National Assembly:

The BDP won 37 seats, on the basis of 46.5% of the vote, boosted mainly by its longtime supporters across rural Botswana. Its chief opposition, the Umbrella for Democratic Change (UDC), a coalition of different parties united under the leadership of human rights attorney Duma Boko, won 17 seats on the strength of 30.0% of the vote, chiefly from disenchanted urban voters in the capital city of Gaborone. A third party, the social democratic Botswana Congress Party (BCP), won another 20.4% of the vote and three seats.

But the election may pale in comparison with the fight that now appears underway between Khama and Botswana’s parliament, including many members of Khama’s own governing party, which is divided into a Khama-led faction and a more independent faction pushing for greater constitutional reforms.

The current fight is over how the next vice president will be selected. Khama wants the parliament to vote by a show of hands; his opponents prefer the more traditional secret ballot, arguing that Khama’s increasingly strong-fisted rule — Khama created the Directorate of Internal Security during his first term and has been accused of harboring authoritarian tendencies — could endanger longstanding democratic checks and balances:

Speaking anonymously, a group of MPs from Khama’s Botswana Democratic Party said they fear he may be attempting to create a “dynasty”.

“The founding president was the father to the current president. Now the president wants his younger brother, another Khama, to succeed,” said one MP. “We cannot allow a Khama dynasty in Botswana. This is not a family party.”

The country’s high court will hear a case about the secret ballot vote on November 6, leaving its government in a week-long state of limbo. No matter the result, the fight showcases the greater scrutiny that Khama will face from an enlarged and empowered opposition.

Botswana’s extraordinary diamond-based wealth has allowed it to develop some of the region’s strongest social welfare protections and given it a measure of stability rare in a neighborhood that includes civil-war torn Mozambique, Robert Mugabe’s Zimbabwe and South Africa, with its own racial and inequality struggles.

Under a 50-50 joint venture, known as Debswana, the Botswana government and De Beers share equally in the profits of Botswana’s diamond reserves, discovered shortly after independence, when Botswana was one of Africa’s (and, indeed, the world’s) poorest countries.

The elder Khama also took steps to limit the influence of corruption — today, it’s ranked by Transparency International as the least corrupt country in Africa, and the 30th least corrupt country in the entire world, making it a great deal less corrupt than many southern European countries. Its GDP per capita, of around $7,200, puts it in the company of some of Europe’s poorer countries, and that makes it one of the wealthiest countries in Africa.

Between independence and 1999, the country grew at an average rate of around 9% annually, and it benefits from a strong tourism industry and close trade ties with the highly developed South African economy. De Beers, which recently moved its processing office from London to Gaborone, has allowed for Botswanan workers to take a greater role in processing the raw materials mined in southern Botswana.

But Botswana faces its own set of problems. For much of the past two decades, it had the world’s highest HIV/AIDS rate, despite efforts by successive governments to provide life-saving medications. Agricultural output plummeted with the discovery of diamonds, and Botswana today imports much of its food.

Despite the fabulous wealth that its diamond mines have brought to it, Botswana’s riches will diminish unless it finds a way to diversify its economy and maintain its standard of living. Growth today isn’t as frothy as in Botswana’s first three decades, and its diamond reserves may be gone by 2030. The sooner that the Khama administration (and its successors) tackle the diversification issue with real action, the better.

Khama will have to address that challenge while also balancing tensions within his own party. If Khama doesn’t satisfy the competing factions of his party, a split could cause snap elections and bring about a permanent rupture within the BDP. That makes it more likely that Khama will back away from rumors of appointing his brother as vice president and, instead, appoint a more unifying figure, such as transport and communications minister Nonofo Molefhi.