Photo credit to Xinhua / Reynaldo Zaconeta / ABI.

Photo credit to Xinhua / Reynaldo Zaconeta / ABI.

Though the late Hugo Chávez has been dead for over a year, the progeny of his democratic socialist movement elsewhere in Latin America are thriving — in part by playing much smarter regional politics than Chávez ever did.![]()

Even as Chávez’s heirs in Venezuela struggle to control a growing economic and governance crisis, the other children of chavismo, including Ecuadorian president Rafael Correa and Bolivian president Evo Morales, may be showing how to marry socialist ideology to a more sustainable co-existence with global markets.

All three leaders, including Morales, tweaked investors by nationalizing industries and, in the case of Morales, railing against the international patchwork of neoliberal institutions, including the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

As with Correa and Chávez, Morales came to power with a relatively anti-US disposition, and one of the first things that Morales, a former coca farmer, did upon taking office was to kick US drug enforcement agents out of the country. His steps have de-escalated the militarization and violence involved with US-led efforts to eradicate drug production in Latin America, and have likely emboldened the calls of other regional leaders to call for a new approach to illicit drugs, including legalization.

But if Morales has nationalized industries like a Venezuelan socialist, he’s run them like a Norwegian state manager.

That’s one of the chief reasons that Morales (pictured above), the country’s first indigenous leader, is such a favorite to win reelection to a third term as Bolivia’s president in general elections on October 12. Bolivians will also vote to elect the members of both houses of its Asamblea Legislativa Plurinacional (Plurinational Legislative Assembly).

Bolivia is now one of the strongest economic performers

in South America.

Consider this:

- GDP growth has risen to ever greater heights over Morales’s tenure — 4.8% in 2006, 2.6% in 2007, 6.1% in 2008, a notable crisis-related drop to 3.4% in 2009, but rising to 4.1% in 2010, 5.2% in both 2011 and 2012 and a staggering 6.8% in 2013.

- Bolivian public debt is now just 36% of GDP, and the country has amassed around $14 billion in foreign reserves, as of earlier this year, a staggering amount in light of the size of Bolivia’s economy (around $30 billion).

- Poverty rates have dropped from around 38% in 2005 to just 24% in 2011. Though Latin America has generally benefitted from region-wide drops in poverty declines, Bolivia is setting a brisker pace than most.

Historically, tin was at the heart of the Bolivian economy, and while mining and gas represent more than 70% of Bolivian exports today, tin counts for around 5% of the total, compared to around 37% for natural gas, chiefly shipped to neighboring Argentina and Brazil.

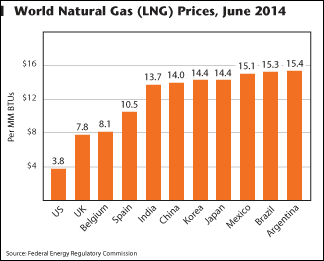

Though that makes Bolivia, whose largest trading partner is Brazil, susceptible to downturns in both the Brazilian and Argentine economies, Bolivia’s own economy is booming while those of its neighbors have slumped. Chalk it up to the high price of natural gas, especially in South American markets to which Bolivia exports:

In addition, Morales has worked for the development of lithium mining in the Bolivian salt flats of Salar de Uyuni, where there are estimates of nearly 5.4 million tons of lithium deposits, an element crucial in battery production.

Photo credit to Anouchka Unel.

Photo credit to Anouchka Unel.

¡Bolivia cambia, Evo cumple! (Bolivia changes, Evo delivers!)

Morales’s management of Bolivia’s current natural gas boom has been much stronger than many of his critics could have believed when Morales first won election in December 2005 (or when he very nearly won election in 2002), and he has governed Bolivia longer than any president since the 1820s.

One of the reasons is that he’s the first indigenous president of a country with an indigenous population of 60% governed for nearly two centuries as a neocolonial fiefdom that, in the half-century before Morales’s rise, crumbled under military rule, economic disaster and political instability. When he came to office, one of the first things Morales did was to require that Bolivia’s civil servants to learn one of the country’s three indigenous languages — Aymara, Quecha and Guaraní.

He’s introduced cash payments for expectant mothers to visit doctors, for families to send their children to school and for retirement funds for Bolivia’s elderly poor. At the end of last year, with an eye on the 2014 election, no doubt, Morales announced a year-end bonus that extended to public-sector employees and even some private-sector workers. None of this, however, places Morales far outside the mainstream — the trend of pairing business-friendly development with social welfare programs (in large part financed by nationalizing the revenues of commodities and energy) is a well-worn path from Chile to Brazil over the last two decades.

That’s also one of the reasons that Tyler Cowen, the well-known economics professor at George Mason University, and certainly no socialist, had some kind words to say about Morales’s reelection bid:

A democratic Bolivia will have “an indigenous government” sooner or later, better sooner. Let’s hope they learn some better economic policy…. Bolivia is too decentralized for the Morales government to collapse into true dictatorship and chavismo of Venezuela. That said, I would feel better if it were assured that the Morales government were to be limited in term.

A caudillo in campesino’s (and cocalero’s) clothing?

Morales’s reelection bid isn’t without controversy, because the country’s new constitution limits presidents to just two consecutive terms in office. Morales circumvented that constraint by counting his second term as only his ‘first’ term under the new constitution. That logic may or may not hold up, but it’s certainly nothing new, even in established democracies — New York City mayor Michael Bloomberg, after all, changed city law to allow a third term in office.

In reality, it’s less controversial because there’s not really much of an opposition to contest Morales’s reelection. Though Morales was never beloved among the political elite, he faces a poorly unified opposition candidate in Samuel Doria Medina, who is running in his third consecutive election, and may win between 10% and 20% of the vote. The Bolivian right has, instead, settled for control of Santa Cruz, the second-largest department within Bolivia after La Paz. In fact, it’s a bit of a surprise that Santa Cruz’s governor, Rubén Costas, isn’t contesting the 2014 election against Morales, though he may be waiting for the 2019 race.

As in Venezuela in the early 2000s, the initial reaction of the Bolivian right to Morales’s victory was its refusal to admit defeat. Rather, the Bolivian right tried, unsuccessfully, to remove Morales though recalls and riots. When those desperate options failed, Santa Cruz and other strongholds of the Bolivian elite tried to secede, which failed just as spectacularly.

As a result, Morales’s Movimiento al Socialismo (MAS, Movement for Socialism) currently rules a virtually one-party state. The MAS controls both houses of the Plurinational Legislative Assembly, holding 88 seats in the 130-member Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies) and 26 out of 36 seats in upper house, the Cámara de Senadores (Senate).

Those margins aren’t expected to change significantly, given the MAS’s dominant position in governing Bolivia and the excellent state of the economy.

Political and economic challenges ahead for Morales

That doesn’t mean Morales will necessarily have a smooth third term.

The rapid development of natural gas fields, as well as increasing lithium exploration, has already inspired growing protests from mining workers, environmentalists and local indigenous communities, some of the groups that fueled the political revolution that propelled Morales to such power.

So far, the MAS has very successfully co-opted those civil society groups. Otherwise, Morales hasn’t been above deploying the brute force of the police and military forces to disperse protests. In one particularly difficult episode in 2010, Morales instructed police to push back indigenous protesters who opposed the construction of a new highway through the Amazon. Eventually, however, Morales backed down and quietly abandoned plans to build the road.

That’s a far cry from the lethal force that Bolivia’s former president Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada used in 2003, at the height of anti-neoliberalism protests. The deaths of nearly 100 protesters forced Sánchez de Lozada out of office and into exile to the United States.

But it’s also a far sign from the kind of respect for civil society that Morales once promised with his inclusive 2002 and 2005 campaigns and the near-unanimous support he enjoyed when he introduced the new constitution in 2009.

Moreover, Bolivia’s natural resources boom might not last forever. Greater trade through an expanded Panama Canal and the proliferation of exports of liquified natural gas could mean brisker trade over the next decade, creating new energy suppliers to South America. Accordingly, Bolivia shouldn’t become accustomed to annual gas-related windfalls, especially if the Brazilian and Argentine economies continue to falter.

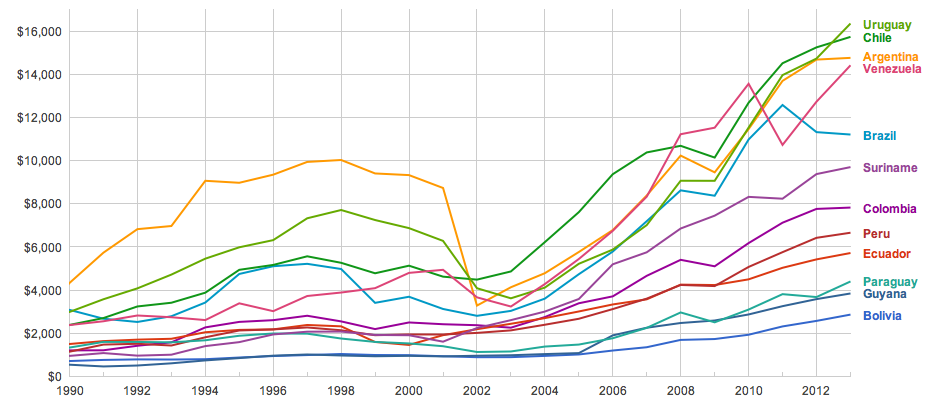

It’s also worth noting that for all of its recent success, Bolivia still lags behind every other country on the most direct measure of national wealth — GDP per capita. Though it’s a measure that’s nearly doubled since Morales first took office, Bolivia remains the poorest country on the continent, a fact that could become more salient if Bolivia’s commodities boom quickly turns into bust.