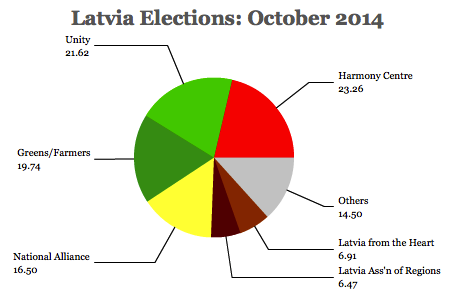

Basically, Latvia’s election turned out nearly as everyone imagined it would. Latvia has had a center-right government since its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and it will do so again. ![]()

A coalition of center-right parties, led by prime minister Laimdota Straujuma, will continue to govern Latvia, continuing the country’s cautious approach to budget discipline. Straujuma, a former agriculture minister, known as a tough negotiator among EU Circles, has won her first electoral mandate since becoming prime minister in January, and she will hope that her country’s low debt and higher economic growth in the years ahead can result in lower unemployment. Even as Russia shakes its sable against NATO, rattling nerves in all three Baltic state, there’s reason to believe that the worst of Latvia’s difficult past half-decade is over.

* * * * *

RELATED: Latvian right hopes to ride Russia threat to reelection

* * * * *

Though it endured a painful internal devaluation and a series of budget reforms over the last five years, Latvia entered the eurozone in January, and Straujuma’s predecessor, Valdis Dombrovsksis, who resigned late last year after the freak collapse of a supermarket roof near Riga, the capital, is set to become the European Commission’s next vice president for ‘the euro and social dialogue,’ making him one of the most important voices on setting EU economic and monetary policy over the next five years.

The opposition Sociāldemokrātiskā Partija ‘Saskaņa’ (Social Democratic Party “Harmony,” which previously contested Latvian elections as the wider ‘Harmony Centre’ alliance), though it won the greatest number of seats in the Saeima, Latvia’s parliament, will be unlikely to find coalition partners in light of its role as the party of ethnic Russian interests and its cozy ties to Moscow and Russian president Vladimir Putin.

Having lost seven seats from its pre-election total, the result will certainly be something of a setback for its leader, Riga mayor Nils Ušakovs, who had tried to emphasize the party’s social democratic nature, even as he offered sympathetic words with respect to Russia’s aggression in Ukraine. It follows a similarly poor showing in the May European parliamentary elections.

Though Straujuma’s party, the liberal, center-right Vienotība (Unity), nominally won three more seats than it had prior to the elections, its position is actually much more precarious now.

That’s because it had merged with another short-lived center-right party, the Reformu partija (Reform Party) of former Latvian president Valdis Zatlers, essentially imploded after its poor showing in last year’s local elections. Together, the two parties held 42 seats in the previous parliament, so the result amounts to a significant setback to the non-populist, non-nationalist right.

Straujuma’s coalition will almost certainly include the nationalist, conservative National Alliance (NA, Nacionālā apvienība) and the populist, agrarian Zaļo un Zemnieku savienība (ZZS, Union of Greens and Farmers).

The unpredictable ZZS, which gained eight seats from the previous election, poses the most troubling risk to steady government. Under the leadership of the mercurial Aivars Lembergs, the ZZS is one of the most conservative ‘green’ parties in Europe, a remnant of the 20th century agrarian parties that boosts the interests of pensioners and rural farmers. Today, the ZZS plays a role that inhibits Latvia’s modernization, and Lembergs, a businessman and the longtime mayor of Ventspils, has for years faced charges of graft and corruption. Though Straujuma will almost certainly need his support to form a stable government, Lembergs will be certain to extract a high price for it.

Two new parties emerged for the first time, either of which could conceivably enter Straujuma’s coalition.

The most promising is the centrist No Sirds Latvijai (‘Latvia from the Heart’), founded by former state auditor Inguna Sudraba, an anti-corruption crusader. Her new party’s nearly 7% support was a bit more than most polls showed it winning, and Sudraba will be a welcome counter-balance against the influence of oligarchic power-brokers like Lembergs.

The other party is the Latvijas regionu apvieniba (Latvian Regional Alliance), which won nearly 6.5% of the vote, was an ten greater surprise. It’s a relatively centrist party as well, but its popularity comes from shock-jock Artuss Kaimiņš, who broadcasts an often crude, if outspoken, radio show called ‘Dog House.’