One of the biggest carrots that the ‘Better Together’ campaign is dangling to undecided voters in the week before tomorrow’s Scottish independence referendum is the concept of ‘devo-max’ — the idea that London will deliver ever greater devolution of policymaking powers to the Scottish parliament in Holyrood.![]()

![]()

Conservative prime minister David Cameron, Liberal Democratic deputy prime minister Nick Clegg and Labour leader Ed Miliband on Tuesday together signed a high-profile pledge to give Scotland greater powers, even without reducing the amount of financial support Scotland currently receives from Westminster.

That is, of course, if Scots vote ‘No’ to independence.

It’s a vow that nationalist leaders, including Scottish first minister Alex Salmond, were quick to dismiss as last-minute gasps of desperation not to be trusted. Salmond, among others, noted that it was Cameron’s insistence on a straight in-or-out vote that eliminated a possible third option for a more federal United Kingdom or some form of devo-max when the two leaders agreed the referendum in March 2013.

Former Labour prime minister Gordon Brown has argued for months that a ‘No’ vote would necessarily require a debate over additional devolution. It might have been strategically wiser if British party leaders, as well as the leaders of the ‘Better Together’ campaign like former Labour chancellor Alistair Darling, had acknowledged the devo-max option earlier. That may be one reason why Brown, who engineered Scottish devolution upon Labour’s 1997 electoral victory, has emerged as such a strong champion for the ‘No’ campaign, despite his national defeat in the 2010 general election. His speech today, less than 24 hours before polls open, was one of the best of the campaign (on either side) and maybe the best of his career.

If a ‘Yes’ vote could endanger Cameron’s premiership, a ‘No’ vote tomorrow could alter Brown’s legacy for the positive.

But as politicians from the left and the right have descended upon Scotland in the last week, with polls showing a much tighter contest than the anti-independence campaign ever anticipated, it’s worth considering three questions about the latest promise of further devolution:

- Has Scotland effectively used its local governance powers in the past 15 years?

- What additional powers might Scotland be granted as part of ‘devo-max’?

- With a general election approaching in May 2015, and with the governing Conservative base firmly rooted in England, is the promise of devo-max something Cameron can legitimately deliver, in light of grumbling from English Tories increasingly frustrated about concessions to Scotland?

Devolution over the past 15 years in Scotland

It’s surprising in some ways that it took until 1999 for Scotland, as a constituent member of Great Britain since 1707, to receive its own parliament. Scots, by a margin of 74.3% to 25.7%, overwhelming supported devolution in the 1997 referendum.

That vote followed a similar 1979 referendum, which failed only because of a requirement that 40% of the registered electorate support devolution. The question, in Wales as well as Scotland, was one of the first priorities of former prime minister Tony Blair after his landslide 1997 election victory.

Scotland held its first elections in 1999, and Scottish voters elected Donald Dewar (pictured above, right, with Blair), a longtime Labour hand, a member of the UK parliament since 1966 and Blair’s first secretary of state for Scotland, as its first-ever first minister, presiding over a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats. Dewar’s death in 2000 led to his replacement by Labour first minister Jack McConnell, who led the Scottish executive for the next seven years.

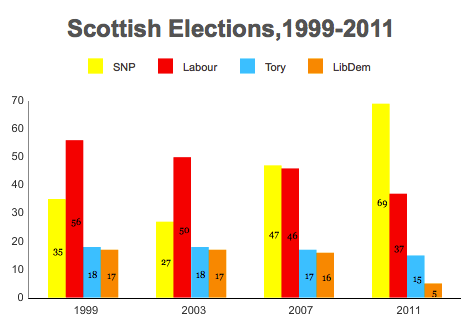

Disenchantment with two consecutive Labour-led governments and the record of Blair’s national government, including his support for the US-led war and occupation of Iraq, led Scottish voters to turn to Salmond (pictured above), who formed a minority SNP government in 2007. In 2011, he won a majority government, despite a mixed-member proportional representation system for electing MSPs designed to inhibit majority governments. The SNP’s landslide victory paved the way for the current referendum, an item upon which Salmond campaigned in 2011. Tomorrow’s vote derives from that election, and you can chart the trajectory of the SNP’s growing strength in Scotland’s four post-devolution elections:

The Scotland Act 1998 was actually much more sweeping than many people remember, even more so than its Welsh counterpart and the Northern Irish devolution that would follow in the early 2000s. The legislation devolved all powers to the new Scottish parliament, except for those specified as reserved matters.

Reserved matters include immigration, defense and foreign policy, nuclear energy and oil, coal, gas and electricity policy, and other constitutional issues, including obligations under international and human rights accords. But Scotland’s parliament currently controls matters like environmental policy, education, housing, law and order, and health and social services.

The Scottish government also has the ability to vary — either lower or higher — the basic rate of UK income tax by 3% within Scotland.

The Scottish variable rate, as it’s called, is set to rise in 2016 to 10% under the terms of the Scotland Act 2012, which creates Revenue Scotland to collect Scottish taxes, allows Scotland to borrow up to £2.2 billion and devolves further powers with respect to drugs and gun policy. Though it was enacted under Cameron’s government, it emerged from recommendations of the Calman Commission, established by the Scottish parliament by the Scottish Labour Party, then in opposition.

But neither the Labour nor the SNP governments at Holyrood have used the Scottish variable rate, in either direction. Nationalists like Salmond argue that an independent Scotland could become like a Nordic social welfare state, but that position might have been more convincing if he had first attempted to do so within the terms of his current powers. Neither Salmond or anyone else has tried raising taxes incrementally to pay for greater social services.

Moreover, as Norman Bonney, a professor emeritus at Edinburgh Napier University, has written, Scottish policymaking over the past 15 years has been profoundly conservative, lacking the kind of radical departures to the left you might have expected in 1999, or even after the SNP victories in 2007 and 2011:

The establishment of the Scottish Government and the Scottish Parliament in 1999 were supposed to lead to a form of more transparent and accountable governance that would free Scotland from the dead hand of decision making at UK level and make government more responsive to Scottish concerns. But the reality of policy outcomes has been much more modest than the rhetoric of political leaders….

Despite avoiding the major structural reorganisations experienced by the NHS in England, and being more generously endowed with public funds, the NHS in Scotland does not seem to have made, under devolution, any fundamental change to the pattern of relatively poor health outcomes.

Though Labour and SNP governments introduced free personal care and free prescriptions, respectively, the reality of a decade and a half of devolution seems at odds with the rhetoric of both the ‘Yes’ and ‘No camps in the current campaign. It may well be that an independent Scotland, for many reasons, would resemble the current Scotland than either the ‘best-case’ or ‘worst-case’ scenarios that the opposing sides are trading.

It’s remarkable just how little devolution seems to have mattered to Scottish policymaking in the past 15 years, excepting some variance in the health care system. Of course, no amount of devolution would allow Scotland to veto British involvement in the Iraq war or determine the status of the Trident nuclear deterrent off Scotland’s west coast. Nevertheless, devolution introduced a new culture of political engagement and democracy that’s resulted in a 97% voter registration rate in Scotland as today’s vote unfolds, including among intensely engaged 16- and 17-year-olds.

What the major parties are now promising to Edinburgh

Cameron, Clegg and Miliband aren’t incredibly clear about what devo-max includes, in part because they haven’t felt incredibly obligated to offer concessions to Scotland. Just last month, the ‘No’ camp had the support of between 60% and 65% of the Scottish electorate.

They have, however, promised to continue to apply the Barnett formula to Scotland, which sets generous funding transfer levels from Westminster to Edinburgh. The formula, which dates to the 1970s, provides greater per-capita government spending for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland — around £1,600 more for the average Scottish citizen than the average English citizen.

In light of the additional devolution in the 2012 Scottish legislation, devo-max would almost certainly give Scotland, which already has more autonomy than a US state or even a Canadian province, something close to full fiscal autonomy.

For his part, Brown rushed out a proposal and a timetable last week (one suspects because among the leading unionists, Brown is the only person who’s given much thought to what devo-max might actually entail). With plans to introduce legislation by January 2015, Brown’s proposal would give Holyrood even more power to set incomes tax rates, though the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats are now openly discussing giving Scotland complete control over its own taxation.

Again, it’s fascinating that the push for greater autonomy follows 15 years during which the Scottish parliament hasn’t availed itself a single time of the autonomy that it already has.

The lingering ‘West Lothian’ question and English backlash

One of the problems with the devo-max approach is that it could spur a backlash among English voters, who worry that Westminster delivers greater autonomy while maintaining greater financial support to Scotland. In short, Scotland gets to have its cake and eat it too. It’s a criticism that English Canadians have often leveled at Québec, which narrowly opposed independence in two referenda of its own in 1980 and 1995.

In the aftermath of Cameron’s pledge to deliver devo-max yesterday, that backlash was underway faster than you could say ‘ah dinnae ken,’ amazingly even before most Scots have voted:

Tory MPs are preparing to publicly savage David Cameron’s handling of the referendum in the event of a No vote, and will attempt to block the plans. One female Tory MP said Mr Cameron’s promise, issued just two days before the polls open, was “desperate”.

“There will be a bloodbath. Last night as I was listening to Cameron saying we are going to be providing all these additional benefits to Scotland, when we are struggling in so many areas of the UK. “It’s all happening on the hoof, in cliquey conversations on telephones in Downing Street. It isn’t happening, and there are a number of us who are incensed who will make sure it isn’t going to happen. But let’s see what the results are first.”

There’s no guarantee that Cameron (pictured above), facing a tough reelection fight in May 2015 and governing a Conservative caucus fractured over EU membership, same-sex marriage, and other matters, could even deliver the kind of devo-max that he has promised to pursue.

If it becomes politically untenable among English voters, the Liberal Democrats, too, might back away. After nearly five years as the junior partners in Cameron’s government, they are already facing a drubbing at the polls.

Presumably, their loss would be the gain of the nationalist, eurosceptic United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP), whose leader Nigel Farage is looking for a populist wedge issue that, aside from the European Union, can drive as much support in national elections as he won in May’s European parliamentary elections. Though he’s found common cause with the anti-Westminster sentiment of ‘Yes’ campaigners, and though he called Cameron ‘moronic’ for not offering devo-max sooner, it’s not difficult to believe that Farage could make political hay among English voters next May.

One of the oddest features of the current debate over Scotland is the so-called ‘West Lothian’ question, named after Tam Dalyell, Scottish MP for the West Lothian constituency in the 1970s, who noted that, in a world of Scottish (and Welsh and Northern Irish) devolution, Scottish MPs in Westminster would continue to influence the policy affairs of English citizens, though English MPs would have limited influence on the policy affairs of Scottish citizens.

It’s an incongruence rooted in the nature of British demographics. England constitutes 83.9% of the United Kingdom’s population — Scotland contributes just 8.4%, Wales 4.8% and Northern Ireland 2.9%. Moreover, the cultural, linguistic and historical differences of the three smaller regions have made devolution a particularly more attractive option than an English-only parliament has been for English constituents. So calls for federalism haven’t traditionally accompanied calls for devolution and regionalism.

It would seem even more alien to divide England into smaller, artificial regions, promulgating a London assembly and a northwest English assembly and a West Midlands assembly, leaving the storied Westminster as a shell for only the most fundamental elements of national government.

Nevertheless, it’s clear that the ‘Scottish question’ won’t end with tomorrow’s referendum, even if Scottish voters reject independence. That result might, in fact, engender an even more difficult and potentially poisonous debate over the UK’s governing structure in the months and years ahead.