A month ago, I scoffed at the idea of holding a presidential election in Syria at a time of civil war, with a pre-determined outcome, while millions of Syrians are living outside the country as refugees, and when fighting is still raging throughout much of Syria.![]()

But a quick look at the turnout indicates that it may have been hasty to discount the election as an exercise in futility — especially coming so soon after a flawed Egyptian presidential election where apathy reigned.

* * * * *

RELATED: Why is Syria holding a presidential election in the middle of a civil war?

* * * * *

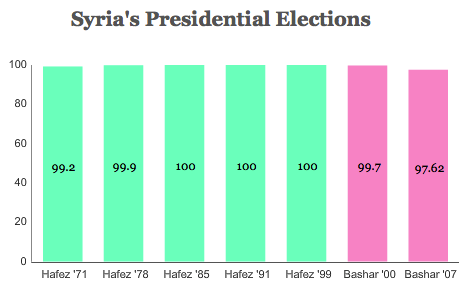

There’s no doubt that the Syrian vote fails by any standard of a free and fair election — by American terms, by European terms, by Indian terms, by Indonesian terms. There was no question that Bashar al-Assad (pictured above), who has been Syria’s president since 2000, would win the vote, just like his father, Hafez al-Assad, remained in power since 1971, typically with somewhat predictable support:

Still, it’s incredible that Syria, where parts of the country still remain under rebel control, the race officially commanded turnout of 73.42%. If those numbers are to be trusted, and that’s a huge question, it means that Syrian turnout, at a time of war, was around 25% higher than turnout in Egypt’s presidential election last week. Stunningly, there are reports of thousands of Syrian refugees living across the border in Lebanon streaming back into Syria earlier this week to take part in the elections. Now, there are also reports that Syrian workers have been essentially forced en masse onto buses to vote:

“Of course I’m voting for Assad. First of all, I can’t not go vote because at work we’re all taken by bus to the polling booth. Second, I don’t know these other candidates. And also, I live here and have no options to leave – I don’t know what would happen if I don’t vote for Assad,” said a teacher in Damascus, contacted on Skype.

But if the point of the election was a show of strength and mobilization among Syrians living within territory that Assad currently controls, the Syrian regime can credibly claim some kind of victory, if not necessarily a democratic mandate.

Whatever the truth, it’s more than the ‘great big zero’ that US secretary of state John Kerry declared it yesterday in a hasty trip to Lebanon, which is still stuck in the middle of a presidential crisis that began last month and that has continued since former president Michel Suleiman left office on May 25.

Though Egypt’s president-elect Abdul Fattah el-Sisi, the former defense minister and army chief, actually won a greater percentage of the vote (96.9%) than Assad has won in Syria (88.7%), turnout in Egypt’s two days of voting on May 26 and 27 was so pitiful that authorities held open polls for a third day, threatening fines to Egyptians who refused to vote. Even then, authorities reported a turnout of just 47.5% — and there’s just as much suspicion that those reported numbers could be inflated, too. But the obvious lack of enthusiasm for el-Sisi, who has been Egypt’s de facto leader since leading a military coup against the elected administration of president Mohammed Morsi in July 2013, will hamper his administration.

Like Assad, el-Sisi has led a brutally authoritarian regime that’s harassed members of Morsi’s Muslim Brotherhood, not to mention other dissenters and journalists, with often lethal force.

But in contrast to Syria, US officials have largely resigned themselves, and have at times, even welcomed, el-Sisi’s rise. In the geopolitics of hard-nosed realism, the United States (and its ally Israel) almost certainly prefer working with a military strongman than a sometimes mercurial Islamist government, however moderate. Even Saudi Arabia, which hasn’t been shy in supporting the radical Sunni, anti-Assad rebels, was delighted at the rise of the Egyptian military to power, given the threat that the Muslim Brotherhood presents as a competing power base within the Sunni Arab world. When it comes to the Saudi national interest (or at least the interests of the ruling monarchy), Sunni solidarity turns out to be less important than stifling the notion of Islamic democracy.

Syria’s election doesn’t mean that Assad has won the war — or even that his regime is no longer in jeopardy. But it could mark a turning point in the civil war, with the fractured and increasingly hardline Islamist opposition losing further ground. Assad now controls nearly all of Syria’s cities and, while the radical Jabhat al-Nusra (al-Nusra Front, جبهة النصرة لأهل الشام) and the even more radical Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS, الدولة الاسلامية في العراق والشام), continue to fight among themselves for control of an increasingly smaller piece of eastern Syria, Assad has consolidated power in Damascus, Aleppo, Homs and otherwise.

Even a year ago, US and other Western officials believed that Assad’s exit was nearly inevitable, and leading US and Western officials were still actively considering arming and other assisting the anti-Assad forces. But while those forces were once dominated by the Free Syrian Army (الجيش السوري الحر, al-Jaysh as-Sūrī al-Ḥurr) and secular former Syrian military officials, they have now been displaced by radical Sunni jihadists. As much as US and European officials despise the Assad regime, they don’t relish the kind of Sunni fundamentalism that a rebel victory would bring to power in Syria, either. That, in turn, might embolden further sectarian violence in Iraq or destabilize the Syria’s smaller neighbor Lebanon, which has so far struggled (largely successfully) to prevent the civil war from overwhelming it.

Assad, whose family belongs to the Alawite (Shiite) minority in a country that’s predominantly Sunni Arab, will likely always face some level of Sunni insurgency in the future. Fighting is certain to continue so long as Saudi Arabia, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates are willing to fund the anti-Assad efforts. But Assad’s allies, Russia, Iran and the Lebanese militia Hezbollah, are as steadfast as allies can be. Other regional players, such as Turkey, that might have hastened Assad’s exit a year or two ago, are now searching for ways to make peace with an Assad victory.

Though it may not be morally satisfying, and though it will ring somewhat hypocritical after the anti-Assad cries over the past three years, expect to see US and Western governments reconcile themselves to Assad rule in Syria throughout the months ahead if he continues to retain a strong grip over the country.