It’s always been somewhat baffling to me why authoritarian rulers and dictators go through the motions of sham elections. ![]()

The voters inside the country know better than anyone else that the elections aren’t a real choice, and in many cases, boycotting the vote or voting for the ‘wrong’ candidate, if a choice is even permitted, can carry perilous results.

International observers aren’t really fooled, either. With the proven work of folks like the National Democratic Institute and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, there’s a 21st century international standard for free and fair elections, and the NDA, OSCE and other similar groups have a thoroughgoing process for certifying the sanctity of elections in developing democracies.

Furthermore, in the world of social media and 24-hour news, it’s harder to carry out the kind of widespread fraud. That doesn’t mean elections are perfect. In Venezuela, the collapse of the state, governing institutions and chavismo mean that a totally fair election is almost impossible. But there’s nonetheless a limit — even with a decade’s worth of dirty tricks, Nicolás Maduro managed only a narrow win in April 2013, for example.

So why is Syrian president Bashar al-Assad pushing forward with an election on June 3?

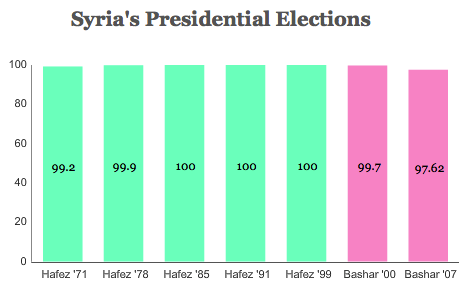

In case you were wondering about the outcome, here’s a chart of every presidential election in Syria since Hafez al-Assad came to power in a military coup in 1971:

In each of the prior ‘elections,’ Syrian voters were presented with a yes-or-no choice on the incumbent, either Hafez al-Assad or, since his death in 2000, his son, Bashar al-Assad.

The first reason is that it’s just time for another election. Every seven years, the Assad regime has held a pro forma presidential ballot. If the Syrian regime can hold a meaningless charade of a vote during ‘normal’ times, there’s no reason why it can’t hold one during a civil war. This holds true enough, I suppose, for more advanced democracies — it’s something of a marvel that the United States held a regularly scheduled presidential election in November 1864, and it’s even more of a marvel that its president, Abraham Lincoln, faced off in an otherwise orderly contest against his former Union general, George McClellan, the nominee of the Democratic Party.

The second — and more compelling — reason is that Assad wants to use the election as a political tool in his own campaign to end the civil war once and for all. By going forward with the elections, Assad is demonstrating that he believes he has enough control over Syria to move forward with the vote. It’s an opportunity to demonstrate that Assad is slowly, but steadily, gaining the upper hand over an increasingly divided anti-Assad rebel force.

Make no mistake — Assad is winning the war. This week, rebels evacuated from Homs, an early center of the anti-Assad uprising that began during the 2011 ‘Arab spring’ revolutions across the Middle East.

In the early years of the Syrian conflict, the anti-Assad forces had been dominated by secular Sunni leaders and former military leaders in the Free Syrian Army (الجيش السوري الحر, al-Jaysh as-Sūrī al-Ḥurr).

Throughout 2013, however, more militant Sunni jihadists (including a number of foreign-based fighters with ties to al-Qaeda) outmaneuvered the more secular leadership. So despite the worldwide anger at the use of chemical weapons in August 2013 against civilians in a suburb of Damascus, the United States and its NATO allies are now hesitant to provide aid to an increasingly radical Sunni opposition. As much as Western governments despise the brutal Assad dictatorship, they might be even more anxious about a radical Sunni state neighboring Israel, Turkey, Lebanon and Iraq.

Lethal infighting, especially between the al-Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra (al-Nusra Front, جبهة النصرة لأهل الشام) and the even more radical Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIS, الدولة الاسلامية في العراق والشام), which used to be the Iraqi branch of al-Qaeda, has enabled Assad to consolidate gains throughout Syria, including its major cities.

Though 74% of Syrians are Sunni Muslim, Assad is an Alawite, a minority sect of Shi’a Islam, which comprises around 13% of the Syrian population. Another 10% of the population is Christian or otherwise non-Muslim.

What’s new this time around is that the regime has allowed two challengers against Assad (out of 24 initial presidential applicants), though no one expects that they will ‘win’ anything but the most marginal support. His two opponents are Hassan bin Abdullah al-Nouri, a member of parliament from Damascus, and Maher Abdul-Hafiz Hajjar, a lawmaker from Aleppo. Neither are particularly well-known among the Syrian electorate. The newly enacted election law prohibits anyone from running who has citizenship of any country other than Syria or who hasn’t lived in Syria for at least the past ten years, thereby excluding most opposition figures that could legitimately challenge the Assad regime.

Photo credit to Reuters.