It’s the most populous state in the world’s largest democracy.![]()

It’s the great heartland of Hindustan along India’s north-central border, home to the Taj Mahal, home to seven of India’s 13 prime ministers, and the traditional base of the Nehru-Gandhi family, which has given India three prime ministers, and hopes to give India its next prime minister in Rahul Gandhi.

It’s Uttar Pradesh (which translates to ‘northern province’), and Narendra Modi’s path to becoming India’s next prime minister runs right through it.

A sketch of India’s most populous state

With 199.6 million residents, it’s nearly as populous as Brazil — and with 80 seats up for grabs in the 545-member Lok Sabha (लोक सभा), the state is by far the largest prize in India’s parliamentary elections, which kick off April 7 and will be conducted in nine phases that conclude on May 12. Given the sheer size of the state, voters in Uttar Pradesh will go to the polls in six of the nine phases,** spanning virtually the entire voting season.

That means that Uttar Pradesh holds about one-third of the seats any party would need to win a majority in the Lok Sabha, the lower (and more consequential) house of the Indian parliament.

Though it lies in the heart of the ‘Hindi belt,’ which might otherwise make it fertile territory for Modi’s conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी), it won’t necessarily be the easiest sell for Modi, the chief minister of Gujarat since 2001.

In contrast to Gujarat, which is one of the wealthiest states of India, Uttar Pradesh is one of the poorest — it had a state GDP per capita of around $1,586 (as of 2009), less than 50% of Gujarat’s equivalent. Much of the state lies on the Indo-Gangetic Plain, making agriculture particularly important to its economy. On every measure, Uttar Pradesh falls behind on many vital economic and social metrics. It has one of India’s highest infant mortality rates (61 per 1,000) and one of India’s lower literacy rates (69.72%). Around 65% of the population is rural and its capital and largest city, Lucknow, has a population of just 2.8 million, making it India’s 11th largest city, and less than one-quarter as populous as Mumbai or Delhi). Nonetheless, Uttar Pradesh is one of India’s more denser states (828 people per square kilometer).

Though 74.1% of the state’s population is Hindu, it has a proportionally higher Muslim population (24.9%) than the rest of India. Given the suspicion with which Indian Muslims regard Modi, dating back to the Hindu-Muslim riots in Gujarat in 2002, the state’s Muslim electorate presents another complication for the BJP.

It was in Ayodhya, a city in Uttar Pradesh, that in 1992 became the scene of some of the worst Hindu-Muslim violence in Indian history when a Hindu riot destroyed the 350-year-old Babri Mosque. More recently, in August and September 2013, riots between Hindus and Muslims in the city of Muzaffarnagar resulted in 49 deaths.

Uttar Pradesh: from Congress heartland to a four-party race

Once a Congress stronghold in the early decades of Indian independence, the BJP began to chip away at its dominance in the 1980s.

In 1998, the first year that the BJP won an national election in India, it won 57 seats (out of 82) in the state. But that would be the last year that any party would win an absolute majority of Lok Sabha seats in the state, because of the rise of two new regional parties, which now have more strength in the state than either Congress or the BJP.

The first regional party is the Samajwadi Party (समाजवादी पार्टी, Socialist Party). Founded in 1992, it first came to power in the state in 1993. Its leader, Mulayam Singh Yadav (pictured above with his son), served as chief minister for the first time from 1993 to 1995 (with a repeat term between 2003 and 2007). His son, Akhiesh Yadav, has been chief minister since March 2012, when the SP returned to power at the state level.

The SP has traditionally vied with Congress to win the votes of the state’s Muslim voters, as well as lower-caste voters identified by India’s constitution under the category of ‘Other Backward Castes’ (OBC). Though the party has provided support to the Singh government and the Congress-dominated United Progressive Alliance (UPA) at the central government level, it is contesting the 2014 race as a member of the left-leaning Third Front in coalition with India’s dominant Marxist party and with the chief minister of Bihar state, Nitish Kumar.

The Bahujan Samaj Party (BSP, बहुजन समाज पार्टी) was founded in 1984 to represent not only OBC, but also dalits (formerly known as untouchables), characterized in the Indian constitution as the Scheduled Castes (SC) and the Scheduled Tribes (ST). The party’s longtime leader is Mayawati (who goes by one name). Like the SP, the BSP leans to the left, but it’s more a vehicle for Mayawati’s political ambition and consolidating dalit support than any real ideology.

Mayawati (pictured above) served briefly as chief minister of the state in 1995, in 1997 and from 2002-2003 before winning a full term from 2007 to 2012 after assembling an odd coalition of high-caste Brahmins and dalits. As chief minister, Mayawati attracted a great deal of attention, including from the international press, as an Indian politician who could one day become the first dalit prime minister. But her blatant accumulation of wealth and her conspicuous consumption is one of the reasons for her party’s fall in the state’s most recent elections.

Among the two regional parties, Mayawati’s BSP is the better bet to support a Modi minority government — though that’s not a sure bet.

Uttar Pradesh as the 2014 battleground

So what does all of this mean for the 2014 national election?

Polls show that the BJP may win up to 40 seats, with the BSP, SP and Congress dividing the remaining 40 seats. That’s assuming that the polls aren’t overstating BJP support, as they did in 2004.

But is that a valid prediction?

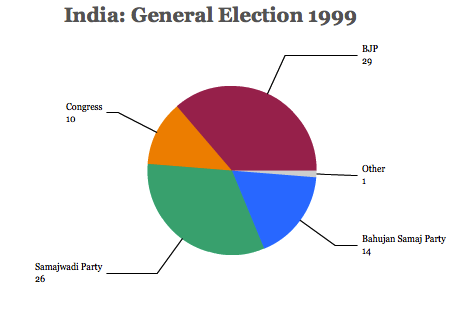

In the 1999 elections, while the BJP won the largest number of seats in the state, it lost 28 seats from its performance just a year earlier, due to the strength of the SP and the BSP:

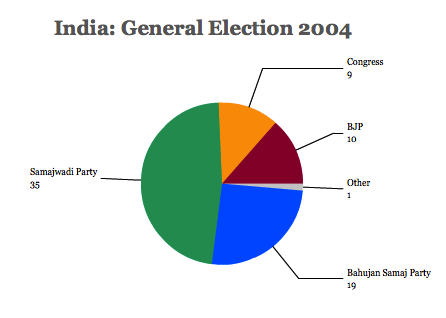

Five years later, in the 2004 general election, BJP prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee was widely tipped to win reelection on the strength of India’s surging economy. Instead, Congress upset the BJP — but in Uttar Pradesh, it actually ended up in fourth place, winning just nine seats, far behind the Samajwadi Party, which at the time controlled the state’s legislative assembly:

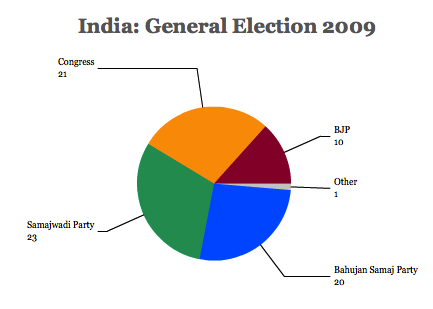

Even when Congress won reelection in 2009 under the steady leadership of Sonia Gandhi and prime minister Manmohan Singh (before India’s economy took its current dive), the party won just 21 seats — still in third place behind the Samajwadi Party and Mayawati’s Bahujan Samaj Party, which by 2009 had once again won control of the local government:

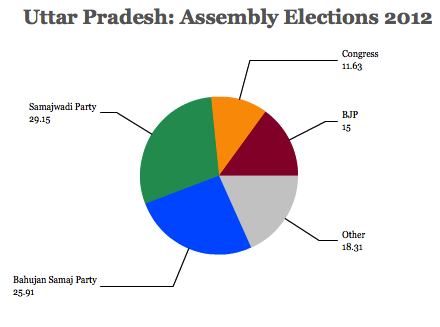

Accordingly, the most recent state-level elections in February 2012 were viewed through the lens of the upcoming 2014 national election. The BJP hoped that its showing would be decent enough to give it a base from which to build for 2014 (even in early 2012, Modi had already emerged as the party’s likely prime ministerial candidate). Congress made an even stronger push, and Rahul and Sonia Gandhi both campaigned vigorously.

The result? A landslide victory for the BSP, knocking Mayawati out of power on the basis of accusations of corruption. The two national parties fell far behind:

The SP holds 224 of the 403 seats in the lower house of the UP legislative assembly. The BSP, even after a landslide wipeout, holds 80, still more than the BJP (47) and Congress (28).

The SP holds 224 of the 403 seats in the lower house of the UP legislative assembly. The BSP, even after a landslide wipeout, holds 80, still more than the BJP (47) and Congress (28).

That means that even with a ‘Modi wave’ across the rest of India, the BJP might not win the huge majority that it hopes — the difference between winning 50 seats in Uttar Pradesh and 20 seats could mean the difference between a clear BJP government and a hung parliament.

As Ajit Sahi writes for FirstPost, projections for a 40-seat BJP win from Uttar Pradesh may be wishful thinking:

In 2012, the BJP was not even runner-up in 70 percent of the 403 UP assembly seats. On a quarter of the seats it even struggled to be fourth. On over one in ten it was fifth; on 16 seats sixth; seventh on three seats; and a shocking eighth on one.

To boot, the BSP and the SP won absolute majorities in the UP assembly elections of 2007 and 2012, respectively, even as the BJP’s seats, in only double digits since 2002, fell further each time. What odds then that the BJP can revive its fortunes in the state based on the supposed popularity of one man? Is Modi bigger today than Lord Ram and Vajpayee were at their best in the 1990s?

A tour of UP’s top constituency races

Nonetheless, the battle for Uttar Pradesh is the battle for India in miniature. Want to know how important Uttar Pradesh is to India’s national elections?

- Narendra Modi, who is also contesting the Vadodara constituency in Gujarat state, will also contest the Varanasi constituency in Uttar Pradesh. Varanasi, formerly known as Benares, a holy city on the banks of the Ganges, is considered India’s most spiritual city. Anti-corruption crusader and former Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, the leader of the newly formed Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी की पार्टी, Common Man Party) is taking the fight to Modi in the same constituency in perhaps the most high-profile contest of the Indian election.

- Sonia Gandhi, the leader of the traditionally center-left Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस) since 1998, is contesting the constituency of Rae Bareli, a seat that former prime minister Indira Gandhi once held.

- In Amethi, Rahul Gandhi, Congress’s unofficial prime ministerial candidate, is running in a constituency he has held since 2004 — and that his father, the late Rajiv Gandhi held between 1981 until his assassination in 1991.

- Maneka Gandhi, the widow of Sanjay Gandhi (Rajiv’s brother) and like Sonia Gandhi, a daughter-in-law of Indira Gandhi, is estranged from the rest of her illustrious family, serves as the MP for Aonla constituency, and is a stalwart BJP member and Congress critic. In 2014, she is contesting the Pilibhit constituency, which she held between 1996 and 2004 before making way for her son, Varun Gandhi, a rising BJP star in his own right, who is contesting the Sultanpur constituency, with hopes for a BJP gain against the Congress incumbent, Sanjay Singh.

- Salman Khurshid, minister for external affairs (India’s equivalent of a foreign minister) since October 2012, and a prominent Muslim attorney and writer within Congress, is running in the Farrukhabad constituency.

- Vijay Kumar Singh, a retired Indian general who previously served as the chief of army staff of the Indian army, and a former commando in the 1971 Bangladesh war, is running as the favored BJP candidate in Ghaziabad constituency. Think of him as the Colin Powell of Indian politics in 2014.

- Mulayam Singh Yadav, the former chief minister, first won a seat in the Lok Sabha in 1957, in 1971 under the Congress banner, in 1989 under the Janata Dal banner, and he has kept the Mainpuri constituency in the Yadav family since 1996. He won the seat easily for the Samajwadi Party in 2009 and is contesting it again this year.

- Chaudhary Ajit Singh, son of a former Indian prime minister, and leader of Rashtriya Lok Dal (RLD), another regional party with strength in western Uttar Pradesh (though without the strength of the SP or the BSP), and a Congress ally within the UPA, should easily hold onto the Baghpat constituency — he’s held the seat (excepting 1998-99) since 1989, and his family has held the seat since 1977.

** If you’re curious, here’s a map of the various phases — constituencies in Uttar Pradesh will hold elections in the following phases: 3rd (April 10), 5th (April 17), 6th (April 24), 7th (April 30), 8th (May 7) and 9th (May 12).