Although everyone expected the governing Serbian Progressive Party (SNS, Српска напредна странка) to win Serbia’s parliamentary elections on Sunday, no one quite expected the Progressives to win such a stunning mandate — the first time in the post-Milošević era that a single party won an outright majority in the Serbian parliament.![]()

Although the Progressives went into Sunday’s election with the largest bloc of seats in the 250-member National Assembly (Народна скупштина), the fluke of the previous elections in May 2012 left the Progressives stuck in coalition with the center-left, nationalist Socialist Party of Serbia (Социјалистичка партија Србије / SPS), and the Socialist leader Ivica Dačić as prime minister instead of a Progressive prime minister.

*****

RELATED: Who is Aleksandar Vučić? Meet Serbia’s next prime minister.

*****

Back in 2012, the Progressives were unwilling to enter into coalition with the center-left Democratic Party (Демократска странка / DS), and Progressive leader Tomislav Nikolić had just defeated Serbian president Boris Tadić, ending eight years of Tadić-led, Democratic government. That gave Dačić, whose Socialists finished a surprisingly high third-place in the 2012 elections, the power to decide whether he would enter government with Progressives or with the Democrats.

After weeks of negotiations, Dačić chose the Progressives. The price for the Progressives was to allow Dačić to become prime minister.

Dačić’s record isn’t incredibly poor — he presided over the official opening of accession talks for Serbia’s ultimate entry into the European Union, his corresponding efforts to integrate Serbia into mainstream Europe have brought Serbia and Kosovo closer to a long-term settlement over Kosovo’s status (and Kosovo’s own future European integration), and the Serbian economy is doing better than it was two years ago, despite a broader push of austerity measures over the 21-month government.

But with polls showing the Progressives with such a wide lead, and with the Serbian left divided between supporters of Tadić and supporters of former Belgrade mayor Dragan Đilas, the tail-wags-the-dog world of a Socialist-led government made increasingly little sense to top SNS leaders, most especially Aleksandar Vučić, the first deputy prime minister who is now set to become Serbia’s prime minister for the next four years. Even before the Progressives essentially demanded snap elections in January, Vučić and his young, Yale-educated finance minister Lazar Krstic were setting more government policy than Dačić.

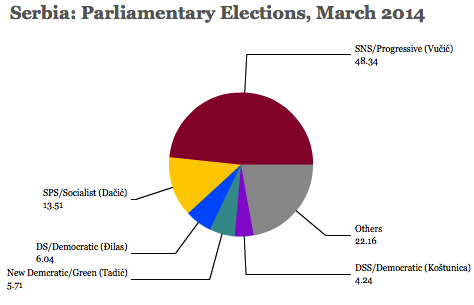

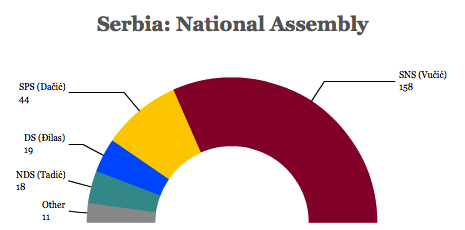

Sunday’s election was a landslide for Vučić and the SNS, which outpolled its nearest competitor, Dačić’s SPS, by more than a 3-to-1 margin. Đilas’s Democrats won just 6% of the vote, and Tadić, leading the alternative center-left bloc, the New Democratic Party/Greens (NDS, Нова демократска странка — Зелени), won just 5.7% and 18 seats.

Vučić now seems free to push through an ambitious agenda of economic liberalization, including a new bankruptcy law, a looser labor law, an anti-corruption push and accelerated privatization of state industries — with the goal of unleashing a stronger Serbian economy as well as bringing Serbia’s laws and economic policy closer in line with mainstream EU policy. Although the Progressives will control an absolute majority in the Serbian parliament, Vučić may yet try to bring one or more of the decimated opposition parties into a wider, reform-minded coalition.

Serbia’s electoral earthquake also shook two longstanding political parties out of the Serbian parliament altogether.

The nationalist, conservative Democratic Party of Serbia (DSS, Демократска странка Србије) failed to achieve the 5% electoral threshold, and it will lose all 22 of its previous seats in the National Assembly — the only time since the party’s foundation in 1992 that it failed to do so (except for its boycott of the 1997 election).

Despite its conservatism, its leader Vojislav Koštunica served as Yugoslavia’s president between 2000 and 2003 (immediately succeeding Slobodan Milošević) and as Serbia’s prime minister from 2004 to 2008 in alliance with Tadić’s Democrats.

The United Regions of Serbia (URS, Уједињени региони Србије), another center-right, regionalist party, won just 3% on Sunday — though it initially supported the SNS/SPS government, it joined the opposition in September of last year.