On January 1, when Latvia celebrated its accession to the eurozone as the 18th member to embrace the single currency, it should have been a moment for Latvian prime minister Valdis Dombrovskis to celebrate shepherding his country into the core of Europe just barely two decades after its independence from the Soviet Union.![]()

Instead, Dombrovskis was counting the last days of his truncated tenure after the collapse of a supermarket roof in a suburb of Riga, the Latvian capital, killed 54 people. Dombrovskis, the 42-year-old wunderkind economist, resigned as prime minister shortly after the tragedy, calling for an independent commission to investigate the incident and arguing that Latvia needed a new government in the wake of the accident.

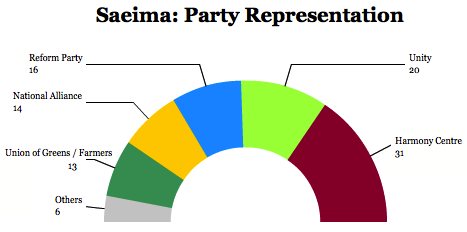

Though it may have been an act of political integrity, Dombrovskis’s resignation came at a nadir for his shaky minority. His party, the center-right Vienotība (Unity), placed third in local elections in June 2013, and disapproval was running high for his government, a coalition that also includes the more stridently right-wing Nacionālā apvienība (National Alliance) and the center-right Reformu partija (Reform Party).

Unity’s decision to nominate Laimdota Straujuma, the current agriculture minister, as its designate for prime minister is designed in part to boost the party’s chances at winning elections expected in October of this year.

The three parties that supported the Dombrovskis have indicated they will back Straujuma, and a fourth, Zaļo un Zemnieku savienība (ZZS, Union of Greens and Farmers), a union of Latvia’s green party and its agrarian party, will join them, along with three additional independent lawmakers. That support will give Straujuma an immediate boost — while the previous coalition controlled just 50 seats in the 100-member Saeima, Latvia’s parliament, Straujuma’s government will command a 16-seat majority:

That means that when Latvian president Andris Bērziņš formally nominated Straujuma as prime minister, it all but assured that she will command a majority to become the country’s first female prime minister.

So who is Straujuma? And what challenges does she face in the months ahead?

Dombrovskis came to power in 2009 facing a contraction that amounted to 18% of Latvia’s GDP, and he’s presided over Latvia’s resurgence. Latvia has achieved some of the highest GDP growth in Europe — 5.6% in 2012 and an estimated 4% in 2013. That growth has come even while Dombrovskis implemented budget cuts to bring Latvia’s debt to one of the lowest levels in all of Europe and forced upon Latvia a sharp internal devaluation — the kinds of wage cuts that have allowed Latvia to become more competitive. Even his push to join the eurozone was controversial, with nearly half the country opposing the move as recently as a month ago, notwithstanding the fact that the previous currency, the lats, was already tied to the euro.

Though it’s hard to miss the resemblance to German chancellor Angela Merkel, Straujuma comes to power as a former civil servant, and there’s no way to know if she’ll last nine months as head of government, let alone nine years. As agriculture minister, she participated often in negotiations at the EU level over the Common Agricultural Policy, which affects Latvian farmers, and she developed a reputation as a tough advocate for Latvia. But she’ll lead a party that’s massively unpopular and a government that she says will follow roughly the same course:

… the new government must not destroy the state budget for this year, [Straujuma] told reporters last night, reports LETA.The next government will have to ensure stability, stressed Straujuma. One of the key priorities, that is “of major importance for businessmen and society”, is preparing a program on absorption of European Union funds for Latvia. The European Commission should approve the program by mid-2014 so absorption of the funds could begin in the second half of the year, emphasized Straujuma.

Unity’s Andris Vilks is almost certain to continue as finance minister in the new government, and Reform’s Rihards Kozlovskis and Edgars Rinkēvičs will remains interior minister and foreign minister, respectively. Jānis Dūklavs, a member of the Union of Greens and Farmers, will replace Straujuma as minister of agriculture, a role that he held between 2009 and 2011 in the first two Dombrovskis governments. Raimonds Vējonis, a former environment minister, will become Straujuma’s new defense minister. The return of the ZZS into government marks something of a return to form in the first two Dombrovskis governments. The rupture came after the last parliamentary elections. Valdis Zatlers, a former conservative president who formed the Reform Party in advance of the 2011 elections and led it to a third-place finish, demanded that the Union of Greens and Farmers not be permitted to join the third Dombrovskis government, labeling it a party of ‘oligarchs.’ Zatlers, in particular, opposed Aivars Lembergs, a wealthy businessman who has been mayor of Ventspils since 1988. Lembergs was previously the ZZS candidate for prime minister, though he’s been under investigation for years on bribery, money laundering and other corruption charges.

Straujuma actually only joined Unity as a party member on January 5 — one day before her formal nomination as prime minister. She previously belonged to the Tautas partija (Peoples Party), which led three governments in the 2000s before voters punished it severely in the 2010 elections, after which the party disbanded.

Unity and the Reform Party, in particular, face the possibility of being wiped out in 2014 elections later this year. The largest (and now only) opposition party, Saskaņas Centrs (Harmony Centre), Latvia’s main center-left party, already holds more seats than any other party in the Saeima, and it will almost certainly improve on that total. The party, a merger between the Socialist Party of Latvia, the National Harmony Party and the Social Democratic Party, has steadily gained seats since emerging as a united force in the 2006 elections.

Voters have been wary to support the Latvian left — the country hasn’t elected a social democratic government in its 23-year post-Soviet history. That’s partly because the Latvian left, including Harmony Centre, attracts the votes of Latvia’s ethnic Russians — at around 26.9% of Latvia’s population, Latvia has a greater proportion of Russians than either Estonia (24.8%) or Lithuania (5.8%). But Nils Ušakovs, its leader and since July 2009, the mayor of Riga, seems the favorite to win Latvia’s next elections and become its next prime minister. The 37-year-old mayor is increasingly popular (even among Riga’s ethnic Latvians), and though he’s clearly more sympathetic to Moscow than other Latvian leaders, it will be harder for the other parties to tar Ušakovs and his party as Russian stooges. His challenge will be to expand the party’s base beyond Riga and the southeastern part of the Latgale region where ethnic Russians are predominant. Ethnicity remains a difficult matter in politics — Latvians chose, overwhelmingly, to reject Russian as an official language in a February 2012 referendum, a vote that fell largely on ethnic lines.

As for Dombrovskis, he’s still young enough to make a comeback, especially if the Latvian economy continues to strengthen and voters give him credit for laying the groundwork of a stronger economy. But he’s also been mentioned as a dark-horse candidate to be the European People’s Party choice to lead the European Commission, and it’s not outside the realm of possibility that he could become Latvia’s next commissioner in Brussels.

Quite an interesting blog, although you are wrong about Harmony Centre, which is a pro-Russian speaker party, not a social democratic party. If a dog calls itself a sausage, does that make it a sausage? Of course not, it remains a dog. And the same holds true for Harmony Centre, whose partner party is Putin’s Mother Russia (surely you don’t consider that a SD party…?). HC has adopted an SD identity in the hope of expanding beyond its ethnic Russian electorate. However, this will fail as ethnicity, rather than a socio-economic left-right divide, is the only key cleavage in Latvia and the Latvian majority will not vote for HC. So a nice intro and almost correct statement of facts (your data on the distribution of deputies in parliament is dated), but your conclusions about where Latvia is heading are a mile off target.

I’ll agree to what Marts said, HC might have some social-democratic traits but it really is a party building its political capital by encouraging national segregation rather than “harmonizing” the society. Ushakovs’ biggest supporters are clearly Russians who are not shy to admit so, while extremely well planned PR accounts for the rest of the popularity.

Another thing: there was 56 majority for the previous government as the 6 MPs, formerly of Reform Party, were part of the coalition. Having said that, the coalition was indeed shaky due to Unity’s and National Alliance’s differences regarding some social and national issues.

While Unity had lost some popularity, the numbers are steady now and it is not likely at all to be “wiped” in upcoming elections — whereas it is true for Reform Party, they have announced now to be joining forces with Unity for the next elections. Whether that means Unity absorbing RP, or them just sharing the ballot is unclear yet.