Yesterday, the new government of Delhi’s national capital territory launched a new anti-graft hotline that received nearly 4,000 calls on its first day.![]()

In what was supposed to be the year of Narendra Modi’s easy rise to India’s premiership, it’s another brash new leader who’s making headlines instead — and not just in India, but worldwide.

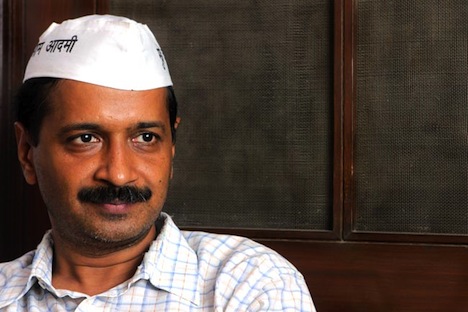

It’s Arvind Kejriwal, the leader of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP, आम आदमी की पार्टी), literally the ‘Common Man’ Party, which emerged as the key player in Delhi’s December regional elections as an alternative to Modi’s conservative, Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (the BJP, भारतीय जनता पार्टी) and the governing center-left Indian National Congress (Congress, भारतीय राष्ट्रीय कांग्रेस) of Sonia Gandhi, the party’s leader; Rahul Gandhi, her son; and outgoing prime minister Manmohan Singh.

Kejriwal, at age 45 one of India’s youngest chief ministers, took office on December 28, leading a minority government that, somewhat ironically, enjoys the outside support of the INC, which controlled Delhi’s government between 1998 and last December’s elections. Congress, which was running for a fourth consecutive term in power under chief minister Sheila Dikshit, was decimated — it not only lost its majority, but now holds just eight seats, after suffering from widespread corruption allegations. Kejriwal actually ran in Dikshit’s New Delhi constituency and defeated her by a margin of 53.5% to 22.2% (state BJP leader Vijender Gupta received just 21.7%).

Though the BJP actually won the greatest number of seats (31 to the AAP’s 28), negotiations between the AAP and the BJP failed, and Kejriwal took up Congress’s somewhat surprising offer to back his government, thereby avoiding a new round of elections. Unlike other regional parties in India, the AAP managed to take power on a broad coalition of supporters, not on the basis of representing certain religious or class-based constituencies — it attracted Muslims and Hindus, rich and poor, Dalit and non-Dalit, and especially India’s educated younger generation.

Kejriwal, a mechanical engineer by training and a former Indian Revenue Service official, started an NGO in 1999 called Parivartan, designed to provide tax assistance and other help to Delhi citizens. But it was as an anti-corruption official that Kejriwal first caught fire in the national spotlight, and under the mentorship of Anna Hazare, worked to demand what would eventually become the Right to Information Act (RTI) in 2005, which required government bodies to reply to citizen requests for information within 30 days or face penalties, and which relaxes many previous exemptions from disclosure under the Official Secrets Act and other legislation. RTI replaced the much weaker, toothless and exemption-ridden 2002 Freedom of Information Act.

In 2011, Anna and Kejriwal succeeded in pushing the government to start the process for drafting a Jan Lokpal bill, an anti-corruption law that would create the Jan Lokpal, an independent citizen’s ombudsman commission that would have the ability to investigate corruption. Though India’s parliament pushed through a Lokpal Bill in December 2013, it’s much weaker than the proposed Jan Lokpal Bill — for example, it doesn’t protect whistleblowers, it doesn’t provide for any real punitive actions or the ability to prosecute corrupt bureaucrats, and it doesn’t provide investigative independence to India’s Central Bureau of Investigation. Kejriwal took the final leap into elective politics when he founded the AAP in November 2012 with the intention of contesting Delhi’s local elections.

Having now swept to power in Delhi (literally on the image of a broom ‘sweeping’ corruption away), Kejriwal wasted no time in announcing a 50% cut in power rates and free water to Delhi residents within hours of taking power. He’s already working to implement the AAP’s anti-corruption agenda with the anti-graft hotline, and he’s pledged to introduce a Jan Lokpal bill specifically for Delhi soon.

There’s good reason for Kejriwal to be in a hurry — with the AAP’s momentum spreading from Delhi to other parts of India, it could be in a position to make a splash in national politics with the upcoming elections for the Lok Sabha (लोक सभा), the lower house of India’s parliament, which are due before May 31. That gives Kejriwal some time to lay the foundation for what the AAP might be able to accomplish on a grander scale, a down payment on what a national anti-corruption party could enact.

After a decade of rule under Singh’s Congress-led governments, Indian voters are weary with Congress . Its prime minister-in-waiting Rahul Gandhi seems unexciting and disinterested. Indians are displeased with Congress’s reform record and the state of India’s precarious economy. Meanwhile, the AAP has highlighted a growing disenchantment over bureaucratic corruption.

Though Modi, the decade-long chief minister of Gujarat state, promises to lead a BJP government that will bring Gujarat’s high economic growth rates to the entire country, there are doubts both about the extent to which Modi’s ‘Gujarati model’ is responsible for his state’s growth and how (and whether) such a ‘Gujarati model’ could even be translated to a much more diverse national economy. Moreover, the 2002 anti-Muslim riots in Gujarat continue to blemish Modi’s record. Though he recently spoke out for the first time disclaiming any role in the violence, the riots, which resulted in the death of over 1,000 Muslims, will continue to haunt Modi’s campaign and the notion that he can be a trustworthy prime minister for India’s religious minorities.

So what damage might Kejriwal inflict on the status quo? Plenty. Continue reading Meet Arvind Kejriwal, the rising anti-corruption star of Indian politics