It’s been a tumultuous year in Czech politics — a surveillance scandal involving the prime minister’s love triangle brought down the government, a power-hungry president elected in the first direct presidential election earlier this year is working to claw power away from the parliament, and what’s left of the Czech right boils down to a contest between an eccentric Bohemian aristocrat and a multi-millionaire entrepreneur. ![]()

Though it sounds like the long-lost plot of a Leoš Janáček opera, it’s the backdrop to this weekend’s parliamentary elections, which should be no less dramatic than the events that shaped them.

What was once expected to be an easy victory for the country’s main center-left party, the Česká strana sociálně demokratická (ČSSD, Czech Social Democratic Party) now looks it will be a less dominant victory — so much that the Social Democrats are no longer considered a lock to lead the next Czech government. It’s the latest twist in a series of turns that could have major consequences for the economic and political development of the Czech Republic (or ‘Czechia‘ as its current president wants to call it) and its 10.5 million residents, to say nothing of the future expansion of the eurozone within central and eastern Europe.

Nečas’s resignation and the collapse of the Czech center-right

The country’s government imploded in June when prime minister Petr Nečas resigned over a surveillance abuse scandal implicating his chief of staff Jana Nagyova, who is accused of spying on Nečas’s wife at the time. Nečas, who was romantically linked to Nagyova, has since married Nagyova. Nagyova is also implicated in a bribery scandal, whereby she’s accused of trading plum roles in state-owned companies to members of parliament in exchange for their support for the government’s austerity measures. The marriage will make it more difficult for prosecutors to compel testimony from either Nagyova or Nečas against the other now that they are officially spouses.

Even before June, however, Nečas’s government was in jeopardy. His party, once the dominant Czech center-right party, the Občanská demokratická strana (ODS, Civic Democratic Party), was already becoming increasingly unpopular. Its support in polls leading up to the October elections has atrophied, with Czech voters blaming Nečas for the country’s poor economy. In the first round of the January presidential election, the candidate of the Civic Democrats finished in eighth place with just 2.46% of the vote — and that was before the steamy surveillance scandal that toppled Nečas (and Nagyova) from power.

Nečas led a push to reduce the Czech budget deficit to within 3% of GDP, which required an unpopular 2012 budget package that increased the sales tax by 1% and raised the highest income tax rate by 7%. While the plan has largely succeeded and the Czech deficit will fall to around 2.8% in 2013, it’s left a fragile economy even more damaged by government policies that have weakened consumer domestic demand. If there’s any place in Europe where you can say that ‘austerity’ has come at the cost of ‘growth,’ the Czech Republic is as strong a candidate as any — it’s set to contract by 1% in 2013. Though it’s expected to return to around 2% growth in 2014, there are reasons (chief among them Czech demographic decline) to worry about the economy’s long-term health.

That’s left the Civic Democrats reeling and its party chair Martin Kuba scrambling to limit the damage of what will certainly be its worst election result since 1990. Though the party’s new leader Miroslava Němcová (pictured above), a former speaker of the Poslanecká sněmovna (the Chamber of Deputies) is the party’s most popular figure by far, that’s not been enough to reverse the damage of three years of austerity and economic recession.

The rise of the anti-corruption ANO

In the week leading up to the vote, polls showed the Social Democrats losing ground, but not to the Civic Democrats.

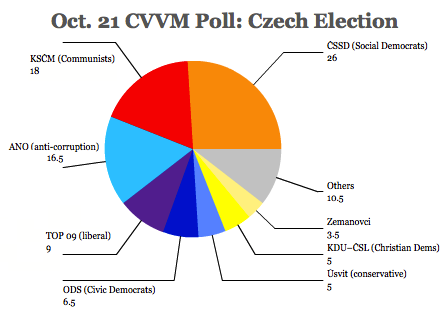

A representative CVVM poll released today shows the Social Democrats dropping, with 26% of the vote, and the far-left Komunistická strana Čech a Moravy (KSČM, Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia) gaining, with 18% of the vote. But the party that’s shown the widest gains in the campaign is a new anti-corruption party, the Akce nespokojených občanů (ANO, Action of Dissatisfied Citizens), founded in 2011 by millionaire Andrej Babiš, which attracts 16.5% of the vote in the poll.

Babiš (pictured above) has led a caustic campaign that’s attacked the country’s ‘pseudo-democracy’ and that has labelled the entire Czech political elite as a bunch of liars and crooks, with a populist campaign message that boils down to, ‘Vote for me — I’m so wealthy, I don’t need to be corrupt.’ His campaign has been so harsh that both the Social Democrats and the Civic Democrats have definitively ruled out serving in government alongside ANO, which probably suits Babiš just fine, given his campaign tone.

Babiš rose to prominence in the business world in the 1990s when he founded Agrofert, originally a food processing and agricultural company, but has grown into an industrial empire with interests in Slovakia and Germany as well as in the Czech Republic, where it’s the country’s fourth-largest business. Though Babiš’s platform is ostensibly more center-right than anything else, he’s emphasized more fundamental business-friendly reforms to reduce corruption, end immunity for politicians and improve the country’s infrastructure.

The country’s second-wealthiest man, who recently bought a top Czech media company, Babiš has been compared to Georgia prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili, an oligarch who won power in last year’s Georgian parliamentary elections and to former Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi, who came to power dominating much of Italy’s privately-owned media and who has dominated Italian politics over the past two decades.

ANO has taken much of the steam out of the liberal Tradice Odpovědnost Prosperita 09 or ‘TOP 09′ (Tradition Responsibility Prosperity 09), whose leader Karel Schwarzenberg, a feisty septuagenarian with aristocratic roots in Bohemia and in Austria, placed a surprisingly strong second place in the country’s presidential election in January. But despite Schwarzenberg’s appeal, voters nonetheless seem likely to punish TOP 09 for its role over the past three years in government — Schwarzenberg served as foreign minister in the Nečas government and TOP 09 deputy leader Miroslav Kalousek served as finance minister.

Accordingly, TOP 09 wins just 9% in the latest CVVM poll, and the Civic Democrats win just 6.5%. While the Social Democrats and Czech Communists have long dominated rural Moravia in the eastern half of the country, the Civic Democrats could collapse in their traditional heartland in the center of the western region of Bohemia, and TOP 09 seems likely to cede much of its support in Prague to ANO.

A hung parliament? Chamber could feature eight different parties

Three other parties win notable support:

Three other parties win notable support:

- The small conservative party, Úsvit přímé demokracie (Dawn of Direct Democracy). It’s essentially the remnants of what used to be Věci veřejné (VV, Public Affairs), which was the third member of the Nečas government coalition until 2012, when internal problems caused the party to implode — and nearly bought down the government down altogether.

- The Křesťanská a demokratická unie – Československá strana lidová (KDU–ČSL, Christian Democratic Union – Czechoslovak People’s Party), which lost all of its seats in the May 2010 election. Throughout the previous 20 years, not only had the Christian Democrats remained a constant presence in the Chamber of Deputies, they never sunk below 13 seats, so the 2010 debacle was a bit of a shock in Czech politics.

- The Strana Práv Občanů – Zemanovci (SPOZ, Party of Civil Rights — Zemanovci), a breakaway group of Social Democrats loyal to Czech president Miloš Zeman, who won January’s election, and who has pushed for greater power vis-à-vis the Czech parliament (more on that later). If the Zemanovci win enough seats to enter the Chamber of Deputies, it’s likely that they will join the Social Democrats in government.

The weekend’s election will determine all 200 members of the Chamber of Deputies, the lower house of the Czech parliament. Deputies are elected by proportional representation, with a 5% electoral threshold, so it’s an open question if the Christian Democrats, Úsvit or the Zemanovici will win 5% and, therefore, any seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

The upper house of the Czech parliament, the Senát (Senate), will not be contested in the weekend’s election. But it’s already controlled by the Social Democrats, who hold 41 of the Senate’s 81 seats (their expected allies, the Czech Communists, hold an additional two seats). In any event, while the Senate can delay legislation, an absolute majority of the Chamber of Deputies can override the Senate’s veto, making the upper house an incredibly weak body.

Sobotka and Social Democrats may be forced into grand coalition

Bohuslav Sobotka (pictured above), the leader of the Social Democrats and Czech finance minister from 2002 to 2006, has run a relatively bland campaign both in terms of policy and personality — he’s pushing for higher business and income taxes to offset additional government spending to boost job growth and spur economic activity, and he’s also pushing for an increase in the minimum wage. Sobotka was widely expected to form a minority government, with the Czech Communists providing support on an issue-by-issue basis outside the government. That’s already a sea change in Czech politics, given that the party is the successor to the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, which governed the country from 1968 to 1990 with an iron fist. Though the current Czech Communists have moderated their agenda to fit a post-Soviet world, they remain an unapologetically communist party, and it’s striking that they could win up to one-fifth of the vote.

But if the two parties fail to win an absolute majority, Sobotka may be forced to look to a ‘grand coalition’ of the kind that currently governs neighboring Austria (and is likely to govern Germany soon as well), especially if the major Czech parties continue to refuse to align with ANO in any future government.

Kuba and the Civil Democrats are open to joining a ‘grand coalition,’ but Sobotka has so far refused to entertain that possibility.

Despite espousing a pro-growth agenda, Sobotka may find himself with narrow options if he does win the weekend’s elections. The next Czech prime minister will almost certainly face pressure to maintain the fiscal discipline to keep the country’s budget within 3% of GDP and to move the country closer to joining the eurozone, thereby limiting Sobotka’s ability to spend too much to boost the Czech economy.

Showdown brewing between Zeman and Sobotka

Complicating matters is Zeman (pictured above), who has incessantly muscled his way into the center of Czech politics throughout 2013.

The Czech president has always had more power than most ceremonial heads of state. He plays a strong role in setting Czech foreign policy, he can veto bills passed by the Czech parliament and he appoints judges to the supreme court and constitutional court and the members of the Czech national bank and the office that implements the Czech budget. But Zeman argues that his direct election by the Czech people gives him a mandate to assume more power than when the president was selected indirectly by the Czech parliament.

Following the fall of the Nečas government, Zeman ignored calls from the Civic Democrats and TOP 09 to appoint Němcová instead. He also ignored calls from Sobotka and within the Social Democrats for new elections.

Instead, Zeman appointed a new technocratic prime minister, Jiří Rusnok, a former finance minister from 2001 to 2002, who was largely viewed as a Trojan horse who would lead a Zeman-dominated government. Rusnok’s failure to win a vote of confidence in the Czech parliament in August, however, set the course for early elections in October. While Zeman couldn’t muster enough support to float Rusnok’s government through 2014, Rusnok has nonetheless served as the caretaker Czech prime minister since July, and Zeman used Rusnok’s appointment as an opportunity to undermine Sobotka within his own party.

Although Zeman left the Social Democrats in 2007 over a spat with the party’s leadership at the time (he founded the Zemanovici in 2009), the Social Democrats remain split over whether to reconcile with Zeman. The party ran its own candidate for president in January, and it remains largely divided between a pro-Zeman wing led by deputy leader Michal Hašek and a more anti-Zeman wing led by Sobotka.

Although Sobotka remains the favorite to become the next Czech prime minister, he’ll immediately face a challenge from Zeman, who as a former Social Democratic prime minister, will want to direct as much of the next government’s policy as possible. The likely new finance minister, Jan Mládek, shares Zeman’s sympathetic view of Russia, and Zeman may ever try to appoint Hašek as prime minister instead of Sobotka.

Why the Czech election matters

From the Prague Spring in 1968 to the ‘Velvet Revolution’ of Václav Havel and others in the late 1980s, the Czechs often found themselves on the front lines of the Cold War.

Though Czechoslovakia peacefully split into two countries in January 1993, the Czech Republic continued to set the pace for the former Soviet-aligned states as a star of the emerging central and eastern Europe. Havel, as the country’s first president, was internationally well-known as a poet, writer and dissident. His successor, Václav Klaus, developed a reputation as Europe’s cantankerous uncle — a strident economic conservative and eurosceptic, who registered a decade-long challenge to the eurozone and greater European integration, sometimes to the dismay of his own government. Nonetheless, the Czech Republic was at the vanguard of the European Union’s 10-member enlargement in 2004. As the western-most of the 10 new EU members and with close ties to Germany and Austria, you might have expected the Czech Republic to lead the way for the new EU members both economically and politically.

But that hasn’t been the case — five of the 10 new members have already joined the eurozone (including Slovakia), and a sixth (Latvia) will join on January 1, 2014. It is the Polish economy, not the Czech economy, that’s best weathered Europe’s latest recession, and it is Polish prime minister Donald Tusk and Polish foreign minister Radosław Sikorski who are mentioned as candidates for top European Union offices. Despite the Czech Republic’s unwavering commitment to fiscal discipline, it’s been the Baltic states — especially Latvia and Estonia — that have become the textbook examples for the pro-‘austerity’ camp that believes tighter budgets can, by restoring credibility and reducing public debt, boost long-term growth. Even Slovakia has posted higher GDP growth in recent years, despite the fact that its membership in the single currency has stripped it of its monetary policy autonomy.

The next Czech government faces the unenviable task of trying to turn that around.

If the Czech economy fails to improve, it could encourage further extremist elements on the left and empower more political instability, such as the rise of new and untested political parties like ANO. If the Czech government fails to maintain the country’s course to join the eurozone, however, it could leave the country even further behind as Poland and other countries seem resigned to moving toward greater economic and monetary integration.

With Zeman showing no signs of backing off his push to consolidate more power within the Czech presidency, the next Czech government will face these daunting tasks while simultaneously fighting over the constitutional lines between the executive and parliamentary branches of government.

Photo credit to Filip Jandourek / Radio Prague. Top photo credit to Kevin Lees — the view from Wallenstein Palace, Prague, December 2005.

2 thoughts on “New Czech party hopes to ride anti-corruption momentum to election gains”