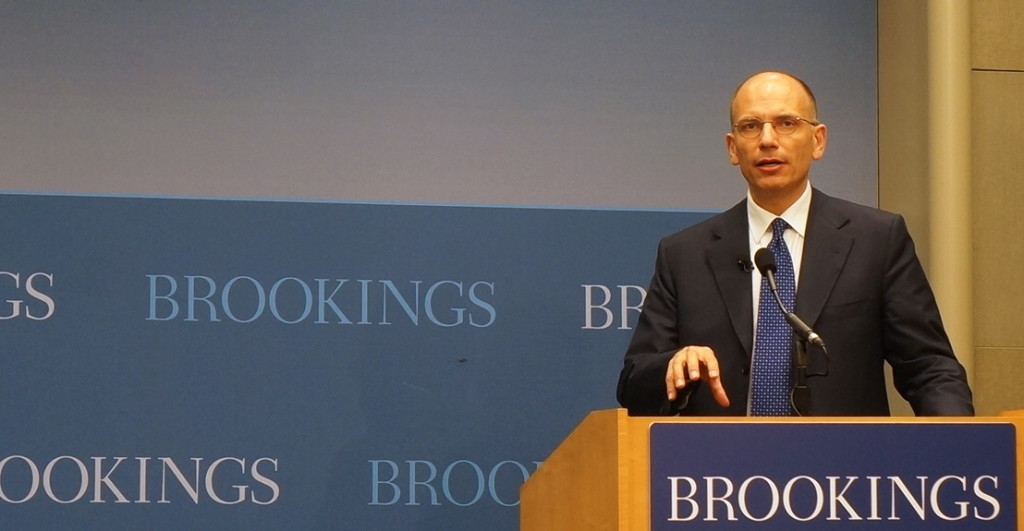

It’s astonishing that in his hour at the Brookings Institution earlier today, Italian prime minister Enrico Letta mentioned ‘Tea Party’ once, but the words ‘Berlusconi,’ ‘Lampedusa,’ or even ‘election law’ never escaped his lips. ![]()

Letta said that he was following with interest the current political standoff in the United States over the debt ceiling and the government shutdown, especially with respect to the relationship between debt yields and political stability. Letta, who is in Washington DC this week, met with US president Barack Obama earlier today, the day that the US federal government reopened after a 16-day shutdown:

This is why… I was so interested in understanding what’s happening here [in the United States], the discussion with the tea parties, the Republican Party and so on. It was something very interesting for me, of course, because of the future of the discussion of the political parties and of the discussion around the problem of the debt, around the problem of how to deal in a bipartisan way.

It’s saying something quite spectacular when an Italian prime minister, who leads Italy’s 64th postwar government, can compare the instability of the American political system to that of Italy’s system, where, most recently, former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi tried to cause Letta’s government to fall just 15 days ago. Letta leads a ‘grand coalition’ among his own party, the center-left Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), Berlusconi’s center-right Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom), and a small group of centrists led by former technocratic prime minister Mario Monti.

Despite the precarious nature of Italy’s coalition government, Letta — with a professional, earnest, mild-mannered mien — has tried to project an aura of stability. Letta is keenly aware that the perception of Italy’s own political instability could be the difference between a future of economic growth and dynamism and a future of demographic decline and economic stagnancy.

From today’s remarks, you may have gotten the sense that Letta thinks that a more integrated European Union and greater domestic political stability will be enough to transform Italy — he even said that the difference between the Italian government’s paying 3% interest rates and 6% interest rates is the difference between the sun and the moon.

But does a solution to Italy’s political and economic problems lie solely in the balance between 3% and 6% yields?

In the decade before 2008, Italian GDP growth averaged just 1.55%, and that’s a decade that saw debt yields largely converge within the eurozone, a decade in which most European economies expanded and even overheated. If you’re a young, ambitious person in Italy today, chances are that you’d sooner look for work in the United States, the United Kingdom, France or Germany before sticking around in Italy. As Edward Hugh has written, peripheral Europe faces an existential death spiral — as European workers increasingly flock to the continent’s centers of economic growth, peripheral national governments will face the prospect of slower economic growth and less revenue, but an even greater obligation to fund a social safety net for a less productive and increasingly aging population.

The answer seems to be greater European economic integration. And Letta is certainly one of Europe’s more visionary leaders with respect to further integration. Today, he called for the eventual end of a dual-headed European Union, with the European Commission president and the European Council president competing for power and influence. He’s right about that — does Council president Herman Van Rompuy run ‘Europe’ or does Commission president José Manuel Barroso? Or is it neither? Perhaps German chancellor Angela Merkel or European Central Bank president Mario Draghi, whose July 2012 ‘whatever it takes’ statement seems to have definitely ended the most acute phase of the eurozone’s sovereign debt crisis. Arguing that the ECB is the only true European-wide financial institution, Letta called for further banking union and deeper financial integration — and all of that makes sense. Nonetheless, the European Union’s glacial pace means that the gains for Italy might not come for a decade or more.

When Letta discusses his plans with respect to Italy holding the rotating six-month European Council presidency in the second half of 2014, it’s an open question if Letta will even still be around to lead the government. Early elections are more likely than not in 2014.

National governments still matter.

In the meanwhile, while Letta’s government hasn’t even passed the six-month mark, there’s little optimism that he can push through the kind of ‘structural reforms’ to streamline and liberalize the Italian economy or political reforms that could introduce greater stability. While everyone in Italian politics agrees that the current election law is flawed, there’s little agreement about what a new election law would entail — any new elections in the foreseeable future are almost certain to mean that no one party or electoral coalition can win control of Italy’s upper house.

Though Letta’s call for ‘structural reforms’ remains loud and consistent, there’s even less optimism that Letta’s government has the political mandate to take action in that regard. Though Italy’s public debt remains among the highest in Europe at around 133% of GDP, mostly due to the legacy of profligate governments in the 1970s and 1980s, its relative fiscal discipline over the past decade means that it is already running a primary budget surplus (i.e. before interest payments). That means that the policy solution for Letta (or Monti or Italy’s next prime minister) lies less in cutting spending or raising taxes and more in reforming Italy’s economy to make it more efficient and productive. Meanwhile, Southern Italy remains one of the eurozone’s least developed regions, and to the current toxic mix of corruption, economic dysfunction, massive unemployment and organized crime.

But urgent though the task may be, there’s certainly less urgency in Italy today than there was in November 2011, when Monti took over as prime minister. Even then, Monti only succeeded in passing a few reforms in his 15-month government, including a crackdown on tax evasion, a slight increase in the minimum retirement age, minor labor market reforms and around €20 billion in budget cuts. The political will to enact even more radical reforms today doesn’t appear to exist.