You won’t find it on any election calendar, but the census that ended today in Bosnia and Herzegovina amounts to the most important election in the country’s history since emerging from the brutal war that resulted from the breakup of Yugoslavia in the early 1990s.![]()

![]()

![]()

The current governing structure of Bosnia and Herzegovina is a mess — the country remains divided largely on the lines of the Dayton Agreement from 1995, and a tripartite government more or less guarantees power to each of the country’s three main ethnic groups — Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats — even while the country itself remains divided between the Federation of Bosnia-Herzegovina (51% of the country) and the Serb-dominated Republika Srpska (49% of the country).

That governance framework effectively ended the gruesome fighting and ethnic cleansing that upended not only Bosnia and Herzegovina, but the entire former Yugoslavia two decades ago. But it’s a governing structure that has inhibited the country’s political and economic development to the point that the Dayton-era mechanisms have been denounced by the European Court of Human Rights and EU leaders are demanding fundamental constitutional changes in order to begin talking seriously about the accession of Bosnia and Herzegovina to the European Union.

Into this volatile mix comes this month’s census, which began on October 1 and will officially conclude today. The census attempts, for the first time in over two decades, to provide an accurate count of the country’s various ethnic groups — not just its Bosniaks, Serbs and Croats, but the country’s other minorities as well, including the country’s Jewish, Roma, Albanian, Hungarian, Montenegrin, Ashkali, Slovenian, Slovakian and so on.

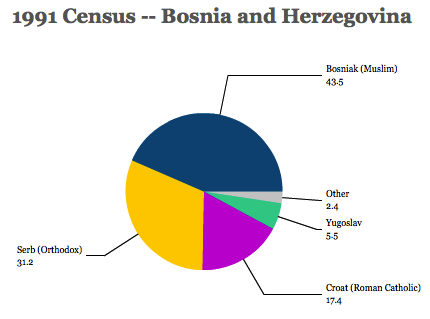

In the last census taken in 1991 (just before the Yugoslav breakup) the population of Bosnia and Herzegovina, then just part of the greater Yugoslav federation, broke down as follows:

That represented nearly a complete reversal from 1948, when Serbs numbered around 44% and Muslims numbered around 30%.

The current census, which was originally scheduled to be conducted in 2012, asks each person to identify three attributes — their ethnicity, their language and their religion, each of are highly correlated in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Ethnicity in the country breaks down largely on religious lines — Bosniaks are predominantly Muslim, Serbs are predominantly Serbian Orthodox and Croats are predominantly Roman Catholic. A 2008 estimate by the Bosnian-Herzegovinian state statistics office found that 45% of the country is Muslim, 36% is Orthodox and 15% is Catholic, setting a baseline for what we might expect the 2013 census to establish more formally in terms of ethnicity. While all three ethnic groups essentially speak the same, mutually intelligible Serbo-Croatian language, there are standard ‘Bosnian,’ Croatian,’ ‘Serbian,’ and ‘Montenegrin’ varieties of the language.

That means that political leaders from within each of the country’s three dominant ethnic groups are pushing hard to maximize turnout, lest one group’s numbers fall behind with constitutional reform likely to come in the years ahead — ethnic leaders want to enter constitutional negotiations from as strong a standpoint as possible vis-à-vis the other ethnic groups. Even Croatia’s government has taken an aggressive interest in the survey by urging Bosnian Croats abroad to vote.

Furthermore, the choice for Bosnian Muslims is even more difficult, who are weighing what it means to be ‘Bosniak’ versus simply ‘Bosnian’ or even ‘Muslim’:

The new census will be the first time the country’s Muslims will have the opportunity to identify themselves as “Bosniaks,” an ethnicity that some Serbs say does not really exist. “For the first time, Bosniaks will be able to declare themselves as Bosniaks speaking the Bosnian language,” says Sejfudin Tokic, the coordinator of a project called It Is Important To Be Bosniak. “This is a historic census — from the Austro-Hungarian period when they were forced to declare themselves as Muhammadans or during the Kingdom of Yugoslavia when a Bosniak identity was not acknowledged, or during Communist Yugoslavia when Bosniaks were forced to declare themselves as Serbs or Croats practicing Islam. In this regard, this is a historic census.”

Between 1974 and 1993, Bosniaks in Yugoslavia were permitted to identify their ethnicity as “Muslim.” After the war broke out, they adopted the term “Bosniaks,” a historic name dating back to Ottoman times. But many Bosniaks are themselves wary of the Bosniak tag, which they see as overly politicized. Some have said they will answer “Muslim” or “Bosnian” when asked about their ethnic identity, a prospect that has alarmed Bosniak political parties.

Bosnia and Herzegovina featured the highest percentage of people who claimed ‘Yugoslav’ as their ethnicity in the 1991 census, which means that a large percentage of the country’s population could simply describe themselves as ‘Bosnian’ this time around. That could be especially true among the younger generation that wants to put the memory of the Bosnian war firmly in the past, even as bullet holes still scar the urban landscape and land mines still dot the rural, mountainous countryside.

By way of background, Bosnia and Herzegovina is just one of several new countries to emerge from the former Yugoslav union at the end of the Cold War:

Some of those countries are doing relatively better than others, but nearly all of them are doing better than Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Slovenia, which lies nestled within Austria’s hinterland, not only joined the European Union in 2004, it joined the eurozone in 2007 and the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2010. Croatia, which sits along the Dalmatian coast and is now one of the hottest tourist destinations in Europe, became the 28th member of the European Union earlier this year.

Montenegro formally entered EU accession talks earlier this year, and Serbia is moving ever closer to accession talks, with European leaders using EU membership as an incentive for further normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo (though Serbia remains far from recognizing Kosovo’s sovereignty). The European Commission has also recommended accession talks move forward for Macedonia, though Greece continues to veto Macedonia’s potential accession over a long-running dispute over which country should lay claim to the name ‘Macedonia.’

But while all of the Balkan countries — and their neighbors — have faced difficult economic conditions over the past five years, Bosnia and Herzegovina falls nearly at the bottom in terms of its GDP per capita:

The Bosnian unemployment rate, as of July 2013, was reported to be 44.6%, making it higher than the 30.9% rate in Kosovo, the 24.1% rate in Serbia, or even what remains a crisis-level 18.4% rate in Croatia. Although the country’s economy made huge strides (a one-time boost of 89% GDP growth in 1996!) with the end of the armed conflict, the economy grew by an average of just 5.4% between 2000 and 2008. That’s strong growth, but it’s hardly the kind of expansion you would expect for a developing country with low labor costs on the periphery of the European single market. Since 2008, Bosnia and Herzegovina has struggled with either contraction or slow growth, and there’s no sign that will change this year. Despite investment from Austria and its Balkan neighbors, foreign investors have largely eschewed Bosnia’s economy. While its currency, the konvertibilna marka (the convertible mark) is pegged to the euro, the country still remains far from integrated into Europe’s mainstream economy.

Part of the reason has to do with constitutional and political challenges.

With the country essentially divided into three ethnicity-based clusters, it has three sets of schools, hospitals and other public institutions. There are even three separate telecommunications companies, all of which provide national service, albeit on solidly ethnic lines — streamlining the three companies into one would mean the loss of jobs within each of the country’s ethnic groups. That’s a powerful incentive to delay or oppose economic reform. Moreover, the country’s political structure has therefore created three times as many opportunities for inefficiency, bureaucracy and corruption, while making it more difficult for the national government to come together for large-scale reforms that could further liberalize the economy. Political quotas mean that there’s pressure to cling to ethnicity for the sake of being hired in the public sector, and the country’s tripartite structure has paralyzed what little economic opportunity otherwise exists:

On paper, the Bosnian Serb Republic has a single market, with free circulation of goods and the same rates of customs and value added tax. But Ms. Cenic said that to operate, businesses often had to bribe or obey politicians in the country’s two main entities, the Serb Republic and the Muslim-Croat Federation. Foreign companies “have to struggle to get all kinds of permissions and guarantees that no one will disturb them, that they will not be racketeered,” she said.

Milorad Dodik, the hardline Bosnian Serb prime minister, keeps a tight grip on economic activity in his fiefdom, but things are messier in the Muslim-Croat Federation, where several layers of administration have to be greased. “The perception of this country is still so bad that serious investors don’t want to risk anything,” said Mladen Ivanic, the former foreign minister of Bosnia and Herzegovina. “The main problem is the political system, not the economic system.”

It’s a political system that’s coming under increasing criticism from outside the country.

The European Court of Human Rights in 2009 ruled by a vote of 14 to 3 in Sejdić and Finci v. Bosnia and Herzegovina that the country’s tripartite government, which guarantees that the presidency rotates among three members (Bosniak, Serb and Croat) for a rotating eight-month term within a larger four-year term, was a violation of the European Union’s Charter of Fundamental Rights. Two Bosnians, one Jewish and another of Roma descent, brought the case to the European court, arguing that their ineligibility to run and serve as president of Bosnia and Herzegovina, violated their human rights.

Despite the ruling, Bosnia’s government has so far failed to amend its constitution in the subsequent four years. That has not only blocked talks to join the European Union, but caused EU accession chief Stefan Fuele to announce plans to halve Bosnia’s pre-accession funding of around €108 million late last week.

Photo credit to ANSA.

2 thoughts on “Bosnia-Herzegovina census highlights tripartite fractures, constitutional problems”