Dylan Matthews at The Washington Post wrote impressively yesterday about the perils of presidentialism and blames the current federal government shutdown not on the individual actors in the US Congress, but on the US constitution itself. Citing the late Juan Linz, who died Tuesday (coincidentally), Matthews points to a body of comparative politics research that shows presidential systems are more likely to fall into dictatorship and chaos than parliamentary systems:![]()

But it’s not just that [James] Madison’s system is unnecessary. It’s potentially dangerous. Scholars of comparative politics have shown that presidential systems with a separation of executive and legislative functions, like America’s, are considerably more likely to collapse into dictatorship than are parliamentary systems where the executive and legislative branches are merged. That’s because there are competing branches of government able to claim democratic legitimacy and steer the ship of state at the same time — and when they disagree profoundly, there’s no real mechanism for resolving the dispute.

But parliamentary systems come with their own challenges. Italian prime minister Enrico Letta, who won a no-confidence vote yesterday after a four-day political crisis spurred by the whimsy of a single, highly volatile opposition leader, may disagree that parliamentary systems are necessarily more stable.

Matthews is right to poke holes in the sanctity with which the US political system holds 18th century governance documents, including the US constitution and the writings of Madison and others (after all, it’s important to remember that the original constitution plunged the United States into civil war — it’s the post-1865 version that includes the 13th, 14th and 15th Amendments that we use today).

We live in a 21st century world that doesn’t always fall into sync with 18th century political economy. The US constitution, whether Americans like it or not, is no longer state-of-the-art technology for constitutions and hasn’t been for decades, and the US presidential system isn’t one that many countries choose to follow these days. When the United States helped craft new political systems in Germany and Japan after World War II, they built parliamentary governments with mechanisms alien to the American system.

But in a world where a minority of one house of the legislative branch of government can shut down the US government, it’s a tall order to ask that American political elites contemplate a major constitutional adjustment — a constitutional amendment to transform the United States into a parliamentary system would require the support of two-thirds of the US House of Representatives and the US Senate and the support of three-fourths of the 50 US states.

While we’re working through thought experiments, can we can lay some of the blame on the nature of the American electoral system? Maybe the United States should elect members of Congress through some form of proportional representation (or ‘PR’) instead of a ‘first-past-the-post’ system — more technically, single-member district plurality.

Although it’s typical to think about PR as a voting system used more often in parliamentary systems, both Canada and the United Kingdom (which have parliamentary systems) use a pure ‘first-past-the-post’ system to elect members to each of their respective House of Commons, while México (which has a presidential system) uses a mixed system that relies heavily on PR to determine members of both houses of its Congress.

How first-past-the-post skews US congressional elections: the 2012 conundrum

In the United States, House members are elected in single-member districts on the basis of ‘first-past-the-post’ voting. That means that the candidate who wins the most votes in the district wins the House seat. Typically in the United States, at least, that means the winning candidate will win over 50% of the vote (or close to it) because of the cultural dominance of the two-party system. That kind of two-party dominance, by the way, is much more likely to develop under the American electoral system (first-past-the-post in single-member districts) than under PR systems. That phenomenon even has a name — Duverger’s Law — and we could spend a whole post pondering the mechanisms and effects of it.

So in the most recent November 2012 US congressional election, Democrats won 48.3% of the national vote and Republicans won 46.9% for the national vote. But Democrats won just 201 seats to 234 for Republicans — the party that won 1.7 million fewer votes nonetheless holds a fairly strong majority of seats in the House (by historical standards).

The skew is even more intense on a state-by-state basis. Here’s a chart that shows five swing states that US president Barack Obama won in his November 2012 reelection bid where Republicans simultaneously won a majority of the state’s congressional delegation — the first column is Obama’s reelection percentage and the second column is the percentage of that state’s House seats held by Republicans:

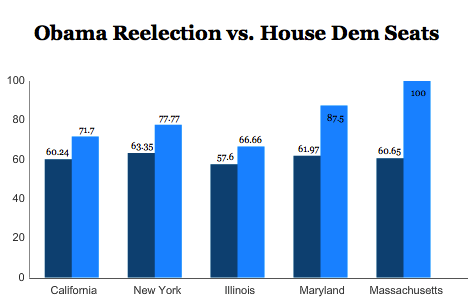

It works both ways — here’s another chart that shows five solidly Democratic states where Democrats hold an outsized advantage in the House. Again, the first column is Obama’s reelection percentage and the second column in the percentage of House seats held by Democrats:

What would proportional representation mean for the US House?

Contrast this to a PR system where seats are awarded on the basis of the party’s overall level of support. There are nearly as many varieties of PR electoral systems as there are countries on the map, but the general idea is that if a party wins 25% of the vote, it should hold 25% of the seats in the legislative body. Often, there’s an electoral hurdle — so a party would have to win 4% of the total vote in order to win any seats in the legislative body.

Both Japan and Germany use a ‘mixed’ system — in Germany, half of the members of its Bundestag are elected in single-member districts and half are elected pursuant to PR. Italy uses PR exclusively, but on a national level for its lower house and on a state-by-state level for its upper house.

Even in countries that don’t use PR, election formulas have made strides beyond the simple system contemplated in the US constitution.

France features a double-ballot election, where candidates must win an absolute majority of 50% in the first round in order to avoid a second runoff election. Australia uses a variant of Ireland’s ‘single transferable vote’ system where voters rank the candidates/parties in order of favorite to least favorite. When the votes are counted, candidates with the least number of votes are eliminated, and the second (and third and fourth and so on) preferences of the eliminated candidate’s supporters are transferred to the other remaining candidates until one candidate has enough votes to win a majority. The Irish/Australian system is often called an ‘instant runoff’ system.

One of the benefits of a proportional representation system is that it would eliminate the possibility of gerrymandering — the process of carving up congressional districts in a way that could favor incumbents, or sometimes, favor one party over another. Political scientists caution that it’s easy to overstate the role of gerrymandering in respect of congressional outcomes (and that Democrats suffer from a kind of natural ‘unintentional gerrymandering’ because so many of their voters are naturally clustered in urban areas, not because Republicans draw them that way). But it can still play a minor role, and the popular misconception that gerrymandering can rig control of Congress might also weaken public trust in the US electoral system.

But pretend for a moment that the United States had a PR system instead!

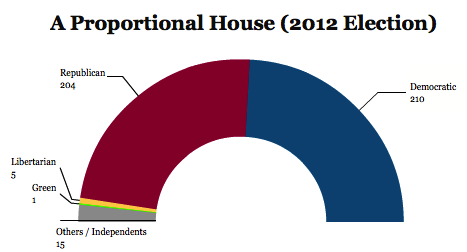

Not only would Democrats hold more seats than Republicans, but in a pure PR system with no electoral thresholds, Congress would welcome two new parties — the Libertarian Party (which won 1.09% of all 2012 congressional votes nationwide) and the Green Party (which won 0.30%). It would also award a handful of seats to independents or others. Moreover, either of the top two parties might have to form a coalition with independents or minor parties in order to form a majority:

If you reimaged the 2012 election results with a more typical ‘electoral hurdle,’ the Libertarians, Greens and others would fall away. Although the United States would still have a House dominated by two parties, it would be a more representative split — and a narrower split than the current House: Democrats 221, Republicans 214.

Open-list versus closed-list: getting around primaries

You can further divide the world of PR systems on the basis of how party members come to hold those seats.

Suppose in the fictional republic of Freedonia, the Purple Party wins 25 seats to the 50-member Freedonian legislature — but who determines which 25 Purplists will get those seats?

In a closed-list system, the Purple Party will draw up a list during the election campaign of candidates, each ranked from #1 to #50. After the election, if the Purple Party wins 25 seats, #1 through #25 on the Purple Party candidate list will become members of the legislature.

In an open-list system, the Purple Party will still draw up a list of candidates, but voters can select the candidates they most prefer. Think of it as a nation-wide electoral district.

If you’ve been paying attention to US politics and the rise of the ‘tea party’ within the past four years, you’ll note the implications here.

Among the headaches of House speaker John Boehner is the relative lack of control that he has over his Republican caucus — in part that’s because the ‘earmarks’ ban means Boehner has fewer carrots to dangle in front of his members.

But it has more to do with three interlocking factors:

- the ease with which incumbents win election to the House (see below), often with margins that would have made the late North Korean dictator Kim Jong-il blush;

- the polarization of American voters within those districts — meaning that more Republicans are representing super-conservative districts and more Democrats are representing super-leftist districts; and

- the rising incidence of intraparty primary challenges — in the 2012 cycle, 13 House incumbents lost primary races to challengers from within their own party, more than all of the successful primary challenges of the past decade taken together.

So Raúl Labrador, a congressman from Idaho, and one of the more conservative House members, has little incentive to cave on the ongoing government shutdown. Back home in the 1st Congressional District, where voters supported Republican Mitt Romney over Obama in the 2012 presidential race by a margin of 64.9% to 32.2%, making a stand against Obama’s health care reform is extremely popular — and his constituents may even think it’s better to shut down the government (or refuse to raise the US debt ceiling) than cave over a health care program that they massively dislike. Even if Labrador is inclined to cave, he now also faces the prospect that he could lose his seat in a future primary challenge if he’s seen as insufficiently conservative.

We don’t know if the primary trend will continue in the future, but the polarization and incumbent reelection trends are decades-long phenomena.

But there’s reason to believe that either an open-list or closed-list system could counteract some of the more polarizing trends in Congress. A closed-list system would give party officials all of the control over the universe of candidates who could win election to the House by taking away that power from primary voters within the party. If that seems too undemocratic for you, an open-list system would allow more voter input, but from among the pool of all voters — and not just the kinds of hardcore Republican and Democratic voters that typically participate in primary elections.

Correction: the original post indicated that Ireland uses a first-past-the-post single-tranferable vote system when, in fact, it uses a proportional representation single-transferable vote system in multi-member constituencies.

I think the primary concern, as I’ve said on Twitter, is the partisan nature of delineating boundaries in the USA. Having a non-partisan boundary committee tasked to creating reasonably equally sized seats with the maximum proportion that are competitive would itself resolve this problem without a change in voting system. In the UK, where this exists, there are still far too many safe seats but it hasn’t reached the ridiculous extents that is has in the USA (though primaries being an occasional novelty may also contribute).

I would however agree with you that (any) PR is more sensible for the USA than FPTP. Congressional districts seem drawn largely on the basis of providing safe seats and given that the biggest advantage to any consituency based system (FPTP, IRV, STV, AMS, SM … it applies to them all to various extents) is that the system allows a community link, a representation of the interest of both people and distinct local communities. I would argue that congressional districts are so arbitrary to have lost that virtue, and that the USA has little to lose from even a list system. It would also serve to reduce the problem of an overly strong two-party system, the problems of an overly fragmented politicial landscape are often put forward but I think that US politics suffers from the lack of choice found with at the opposite extreme, which is just as unhealthy even if it’s less dramatic.

As an aside, Ireland and Australia’s systems are distinct. Ireland uses STV (preferential, usually but not inherently proportional) and Australia IRV (preferential, majoritarian). I’d call the latter a variant on a two-round system á la France, as the name “instant runoff voting” implies, rather than an STV variant.

The fact that they are so different is also, annoyingly, why we in the UK are still lumbered with FPTP. It was agreed to abolish FPTP but parliament were split between adoption of IRV and STV and nothing happened in the end!