One of the odder results of this week’s Norwegian election is that while it boosted the numbers of seats for the two parties that are most in favor of membership in the European Union, Norway is today less likely than ever to seek EU membership.![]()

![]()

Together, the center-left Arbeiderpartiet (Labour Party) and the center-right Høyre (the Conservative Party) will hold 103 seats as the largest and second-largest parties, respectively, in the Storting, Norway’s 169-member parliament — that’s a larger number of cumulative seats than the two pro-European parties have won since the 1985 election.

But EU membership is firmly not on the agenda of Norway’s likely new prime minister, Erna Solberg, just like it wasn’t on the agenda of outgoing prime minister Jens Stoltenberg during his eight years in government.

One of the obvious reasons is that EU membership is massively unpopular among Norwegians — an August poll found that 70% oppose membership to just 19% who support it.

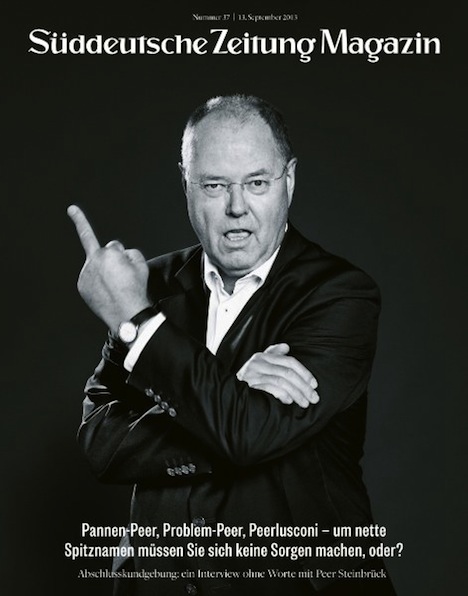

Proponents of EU membership argue that because Norway is part of Europe’s internal market, it is already subject to many of the European Union’s rules. (Norway is also a member of the Schengen free-travel zone that has largely eliminated national border controls within Europe) But until Norway is a member of the European Union, it has absolutely no input on the content of those rules. Stoltenberg (pictured above left with European Council president Herman Van Rompuy) has called the result ‘fax diplomacy,’ with Norwegian legislators forced to wait for instructions from Brussels in the form of the latest directive.

Since 1994, when Norwegians narrowly rejected EU membership in a referendum, Norway has been a member of the European Economic Area (EEA), an agreement among the EU countries, Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein that allows Norway and the other non-EU countries access to the European single market.

Opponents argue that Norway, with just 5 million people, would have a negligible input in a union that now encompasses 28 countries and nearly 508 million people. They also argue that with one of Europe’s wealthiest economies, Norway would be forced to contribute part of its oil largesse to shore up the shakier economies of southern and eastern Europe. There are also sovereignty considerations for a country that didn’t win its independence from Sweden until 1905 — and then suffered German occupation from 1940 to 1945. Though Norwegians also often cite the desire to keep their rich north Atlantic fisheries free of EU competition, Norway already has a special arrangement with the European Union on fisheries and agriculture, and it’s likely that it would continue to have a special arrangement as an EU member, in the same way that the United Kingdom has opted out of both the eurozone and the Schengen area and has negotiated its own EU budget rebate.

Though Solberg herself is from Norway’s western coast, her party’s base is comprised largely of business-friendly elites in Oslo and Norway’s other urban centers, where support for EU membership runs highest. But that enthusiasm doesn’t always flow down to voters who support Solberg, and it certainly doesn’t extend to Norway’s other right-wing parties. Continue reading Despite the success of pro-EU parties in Norway, don’t expect EU membership anytime soon