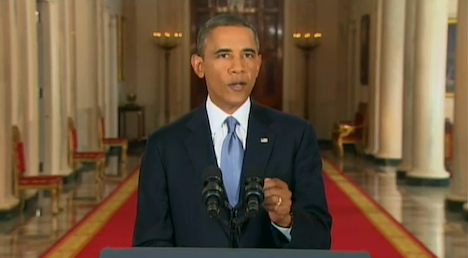

US president Barack Obama’s speech tonight was about as good a speech as you can imagine for someone with conflicting goals — convincing a skeptical audience on both the right and left that US military action may be necessary to punish Bashar al-Assad for last month’s chemical attack while announcing he would postpone a planned vote in the US Congress while Russian, American and other international diplomats work toward a political solution that would result in Syria giving up its chemical weapons.![]()

![]()

![]()

The headline tomorrow morning will be ‘Obama delivers mixed messages,’ but given the dueling tasks on the US efforts over Syria, that was always going to be the case.

In the meanwhile, here’s where I believe Obama succeeded and where Obama failed tonight.

He succeeded in explaining why chemical weapons are so bad:

This was not always the case. In World War I, American GIs were among the many thousands killed by deadly gas in the trenches of Europe. In World War II, the Nazis used gas to inflict the horror of the Holocaust. Because these weapons can kill on a mass scale, with no distinction between soldier and infant, the civilized world has spent a century working to ban them. And in 1997, the United States Senate overwhelmingly approved an international agreement prohibiting the use of chemical weapons, now joined by 189 government that represent 98 percent of humanity.

Mentioning that ‘98% of humanity’ has adopted the Chemical Weapons Convention drew a bright line, and Obama made a strong case as to why chemical, biological and nuclear weapons are especially vile. There’s always been a strong case for the United States and the international community to respond forcefully to the August 21 attack, and Obama eloquently outlined the nearly century-long fight to ban weapons of mass destruction. For the record, that 98% of humanity doesn’t include Israel or Egypt, the top two recipients of US foreign aid. It was a good line, but the United States could win a lot of goodwill by pressing its Middle Eastern allies to ratify and/or sign the convention along with Syria.

He succeeded in projecting that he’s not keen on launching a war. The most heartfelt part of the speech was his statement that he is loathe to start yet another war in the Middle East:

Now, I know that after the terrible toll of Iraq and Afghanistan, the idea of any military action, no matter how limited, is not going to be popular. After all, I’ve spent four and a half years working to end wars, not to start them.

It’s absolutely credible, and from the beginning of the Syrian civil war over two years ago, Obama has taken pains to distance the United States from getting bogged down in another Middle Eastern conflict. Obama was elected president on perhaps the most successful antiwar presidential campaign in history, and he certainly doesn’t want to get embroiled in a lose-lose situation in Syria in the final three years of his presidency.

He succeeded in coining a new term: ‘The United States doesn’t do pinpricks.’

It’s pretty amazing that we’ve gone from ‘shock and awe’ on the eve of the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 to all the talk of how a potential Syrian strike would be, in US secretary of state John Kerry’s words, ‘unbelievably small.’

But the White House must prefer a world where Syria hands over its chemical weapons through diplomatic means (backed up by thorough UN inspections), thereby keeping those chemical stocks out of the hands of both the Assad regime or any potentially Sunni Islamist government that follows it than a world where the United States launched non-pinprick missile strikes against the Assad regime, which may be less effective in dissuading the Assad regime or others from using chemical weapons in the future — especially if Assad emerges emboldened from the attack.

He failed in explaining just how Assad is culpable. Here’s what Obama had to say about the Assad regime’s culpability:

Moreover, we know the Assad regime was responsible. In the days leading up to August 21st, we know that Assad’s chemical weapons personnel prepared for an attack near an area where they mix sarin gas. They distributed gas masks to their troops. Then they fired rockets from a regime-controlled area into 11 neighborhoods that the regime has been trying to wipe clear of opposition forces. Shortly after those rockets landed, the gas spread, and hospitals filled with the dying and the wounded.

We know senior figures in Assad’s military machine reviewed the results of the attack and the regime increased their shelling of the same neighborhoods in the days that followed. We’ve also studied samples of blood and hair from people at the site that tested positive for sarin.

Whatever the US government knows (or thinks it knows) about the Assad regime’s fault for the attack on August 21, it’s certainly been incredibly bashful about sharing it with the rest of us. Middle Eastern armies often distribute gas masks to their troops, and the Syrian army is firing a great number of rockets into a great many neighborhoods these days. That alone tells us nothing — it’s certainly information that can supplement the case for Assad’s blame, but it’s ultimately circumstantial. No matter who was responsible, of course you’d expect Assad’s military to review the results of the attack. Even if sarin were used in the attack, that tells us nothing about who released it — and why. Many commentators, myself included, have outlined all the reasons why the timing of an Assad-ordered chemical attack doesn’t quite make sense.

No one in the Obama administration, including Obama himself tonight, has been willing to say, ‘We know Assad ordered this.’ The closest we’ve heard is that ‘we know the Assad regime was responsible.’ We don’t know if it was a rogue commander, we don’t know if it was an accident. We don’t know if the US government has more solid intelligence on Assad’s culpability or if its determination is based on suspicions. The 1,434-word ‘government assessment’ earlier this month (in which the White House ‘assesses with high confidence’ that Assad is responsible) doesn’t provide a lot of comfort about the quality of US intelligence on the matter.

He failed in bridging the Syrian conflict to Iran’s nuclear weapons program. It’s always been an incredible leap to try to tie the current Syrian conflict to the US and international efforts to negotiate Iran out of its nuclear energy program. For the record, a nuclear energy program isn’t a nuclear weapons program — for all of the suspicions on the US side, there’s little proof that Iran actually wants to build a nuclear weapons program, and Iranian leaders, including Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, have disclaimed nuclear weapons. But it’s hard to believe a US military strike wouldn’t worsen US-Iranian relations, which would be especially unfortunate given the recent election of moderate Iranian president Hassan Rowhani and Iran’s instinctive antipathy toward chemical weapons — in no small part due to the fact that US-backed Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein unleashed poison gas on Iranians in the 1980s with US knowledge. (Read more about the relatively complex Iranian response to the Syrian crisis here).

If the latest diplomatic effort fails, and Obama turns back to a full-throated push for military action, I suspect we’ll hear a lot more about how US action in Syria is tied to Iran’s nuclear program or to Israel’s security. Both are dubious arguments, though.

He failed to explain how the United States would avoid a slippery slope. Obama tried mightily to argue that limited, punitive strikes would not lead to an open-ended, escalating conflict:

I will not put American boots on the ground in Syria. I will not pursue an open-ended action like Iraq or Afghanistan. I will not pursue a prolonged air campaign like Libya or Kosovo. This would be a targeted strike to achieve a clear objective: deterring the use of chemical weapons and degrading Assad’s capabilities.

Obama’s own hesitance about getting involved in Syria is crystal clear, so there’s little doubt he wants a very limited window of action. But no US president can realistically promise that a Syrian attack won’t lead to escalation. What if Assad succeeds in retaliating against US military personnel or citizens abroad? What if Russian warships attack the United States? What if Assad manages to attack US warships? What if he uses chemical weapons again in the future? What if the anti-Assad opposition gets chemical weapons and uses them? To paraphrase another former US official who knows something about Middle Eastern wars, those are just the ‘known unknowns,’ not the ‘unknown unknowns.’ Those aren’t by themselves reasons to shy away from taking action to deter the use of weapons of mass destruction, but it’s simply not a promise any president can make.

He failed to show his cards on the ongoing diplomatic game. Unlike his prior speech over the Labor Day weekend when he announced he would seek a vote of approval in the US Congress, Obama didn’t attack a ‘paralyzed’ United Nations Security Council. But neither did he indicate he is incredibly optimistic about the chances of passing a satisfactory resolution that can win both the US and Russian votes in the Security Council. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, because much of the diplomatic wrangling will take place behind closed doors, not in addresses to the American public. But it’s striking that Obama devoted just seven sentences to the latest, potentially game-changing, development:

However, over the last few days, we’ve seen some encouraging signs, in part because of the credible threat of U.S. military action, as well as constructive talks that I had with President Putin. The Russian government has indicated a willingness to join with the international community in pushing Assad to give up his chemical weapons. The Assad regime has now admitting that it has these weapons and even said they’d join the Chemical Weapons Convention, which prohibits their use.

It’s too early to tell whether this offer will succeed, and any agreement must verify that the Assad regime keeps its commitments, but this initiative has the potential to remove the threat of chemical weapons without the use of force, particularly because Russia is one of Assad’s strongest allies. I have therefore asked the leaders of Congress to postpone a vote to authorize the use of force while we pursue this diplomatic path. I’m sending Secretary of State John Kerry to meet his Russian counterpart on Thursday, and I will continue my own discussions with President Putin. I’ve spoken to the leaders of two of our closest allies — France and the United Kingdom — and we will work together in consultation with Russia and China to put forward a resolution at the U.N. Security Council requiring Assad to give up his chemical weapons and to ultimately destroy them under international control.

2 thoughts on “How Obama’s speech on Syria succeeded and how it failed”