After primary elections earlier this week, Argentina’s president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner is in even more trouble than you might have thought, even though her peronista ruling party seems likely to win elections later this year.![]()

![]()

That Argentina’s political opposition has been divided for over a decade is clear, but at a time when kirchnerismo is as unpopular as ever, there are no signs that the disparate forces opposed to the increasingly isolated Fernández de Kirchner administration are in a position to capitalize on the government’s unpopularity. So while Tigre mayor Sergio Massa, a former Kirchner ally turned opposition peronista, made the largest headlines by defeating Kirchner’s candidate in Sunday’s high-profile primary in the province of Buenos Aires, home to 40% of Argentina’s population, there’s really no movement to unite his opposition movement with the more traditional center-right and other regional opposition fronts in advance of the October 27 midterms. That’s still probably good news for Massa, though, who will have managed to distance himself from the Kirchners without abandoning the resilient peronista label, and winning a test run for the 2015 presidential race in the country’s dominant province.

The country will go to the polls on October 27 to determine one-half of the composition of the 257-member Cámara de Diputados (Chamber of Deputies) of the lower house of the Argentine National Congress and one-third of the composition of the 72-member Senado (Senate), the upper house. The open primaries earlier this week, in essence, functioned as a massive poll indicating where the country might head in those elections — they are not primaries in the traditional U.S. sense whereby candidates from the same political party duel for their party’s nomination, but a gating mechanism to weed out smaller parties from the October midterms.

The good news for Fernández de Kirchner is that her base of support of around 30% of the vote nationwide should be enough to win those elections, especially considering that her party, the ruling Frente para la Victoria (FpV, the Front for Victory), is the only truly national political party in that it is fielding competitive candidates nationwide. Ironically, the Front for Victory did better in the 2011 elections (when it won 78 seats), largely on the strength of Fernández de Kirchner’s reelection, than in the previous October 2009 midterm elections (when it won 38 seats), when the opposition actually outpolled the kirchneristas. That means that, despite the party’s current unpopularity, the opposition will be defending nearly twice as many seats as the Front for Victory due to the staggered nature of Argentine congressional elections — remember that only one-half of the Chamber of Deputies are up for reelection in a given election cycle.

The bad news for Fernández de Kirchner is that former allies are now peeling away from the Front for Victory to run through separate peronista movements as a result of Argentina’s increasingly bizarre economic management and in anticipation of the October 2015 presidential election. If the primary result is an indication of what will happen in 10 weeks’ time, Fernández de Kirchner will not win the two-thirds congressional majority that she would need to change the country’s constitution and allow her to run for a third consecutive term in 2015. Kirchner’s party would have to hold onto every seat they currently have and pick up 55 more seats to command that kind of majority, a feat that would outperform the Front for Victory’s 2011 congressional performance. The bottom line is that the 2013 midterms are an opportunity for potential candidates to break through in what could be the first opportunity in over a decade for an Argentine president not named Kirchner, despite a fiery speech Wednesday to relaunch her party’s campaign for October.

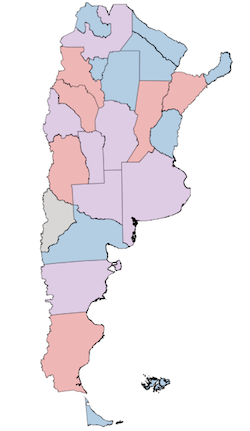

The really bad news is that the Front for Victory placed either second (or worse) not only in Buenos Aires province, but the next three-most populous provinces in Argentina, the federal district and 11 more provinces (in total, 14 out of 23 provinces), including the southern Santa Cruz province that had been her late husband Néstor Kirchner’s base. See below an electoral map from Clarín: blue indicates victory for the Front for Victory; purple for opposition peronista fronts; and red for coalitions dominated by the Unión Cívica Radical (UCR, Radical Civil Union).

That leaves Fernández de Kirchner as a lame-duck president who will preside over an economy that’s now stalled after years of growth — she risks leaving office with few allies on the traditional left or the traditional right and the steward of a new potential Argentine economic crisis. After her husband’s administration defaulted on Argentine debt from the previous decade’s peso crisis, thereby benefitting from nearly immediate economic growth, Fernández de Kirchner has struggled at times to find enough foreign exchange reserves with the country shut out of financial markets, and Argentina, according to at least financial adviser, has an 84.5% likelihood of defaulting in the next five years, and that doesn’t even count the legal embroligio between Argentina and U.S. hedge fund Elliott Associates, a holdout from the prior Argentine debt haircut, that may well go all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court (Felix Salmon at Reuters has made a hilarious video explaining this case here).

That has forced her government to seek out cash in creative ways. Although Fernández de Kirchner backed down from a plan to raise taxes on agricultural products in summer 2008 after massive farmer protests, she instead nationalized around $30 billion worth of Argentina’s private pensions later that year. More recently, she nationalized Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales (YPF), Argentina’s largest energy company previously owned by a Spanish firm, in May 2012. GDP growth slumped to just 2.6% in 2012 and Argentine economists still forecast 4% growth this year, but the country has long struggled with double-digit inflation that many argue is even higher than the government reports.

Once upon a time, in the mid-20th century, you could have thought about Argentine politics in a standard two-party system — the leftist Partido Justicialista (PJ, Justicialist Party) was founded by Juan Perón in 1947, and its more traditionally centrist rival, the UCR, which dates back to the 19th century. A ban on peronista parties that began in the late 1950s and 1960s, a repressive military junta-led government in the 1970s and early 1980s, and the peso crisis of 1999 to 2001 successfully scrambled political lines in Argentina, however.

When Néstor Kirchner won power in 2003, he did so as the leftist of three Justicialist candidates — he became president with just 22.2% of the vote when first-place finisher Carlos Menem, a more right-wing Justicialist and former president, withdrew from a runoff with Kirchner. Shortly thereafter, Kirchner founded the Front for Victory, largely comprised of the old peronista Justicialist party, although anti-kirchnerista Justicialists and peronistas both have emerged over the past decade. That fragmentation has typically been to the advantage of the Front for Victory and the Kirchners. When Fernández de Kirchner won election in her own right in October 2007, she did so with just 45.3% of the vote, though her nearest rival, centrist Elisa Carrió won just 23%. When she won reelection in October 2011, a year after Néstor died suddenly from a heart attack, she won an absolute majority (54.11%) with an even more widely dispersed slate of opponents.

Looking at the results of the weekend’s primaries at the province level demonstrates just how this plays out nationally.

Massa (pictured above), who became mayor of Tigre, a suburb of Buenos Aires, in 2009 and has focused on a chiefly popular agenda of crime prevention, got his start as a Kirchner ally, first as the top administration at ANSeS (the Argentine social security administration), then as a kirchnerista deputy, then as the cabinet chief from 2008 to 2009. But Massa broke with Fernández de Kirchner to form a new peronista group, the Frente Renovador (Renewal Front), to contest this year’s midterms in Buenos Aires province, home to over 15.5 million of nearly 41 million Argentines. Massa won the province with 35.1% of the vote to just 29.7% for Martin Insaurralde, the little-known candidate heading the Front for Victory’s campaign. That gap is certain to widen as other centrist opposition groups line up behind Massa.

It was even worse for the kirchneristas in Buenos Aires proper, where a coalition of UCR, the Partido Socialista (PS, Socialist Party) and other center-left parties won 35.6% in aggregate in the federal district, home to nearly 3 million porteños. The conservative Propuesta Republicana (PRO, Republican Proposal), the party of Buenos Aires mayor Mauricio Macri, another potential 2015 presidential aspirant, won 27.5% and the Front for Victory ended up in third place win 19%. In Córdoba, the country’s second-most populous province, the peronista alternative Unión por Córdoba (Union for Córdoba) won 30.1%, the UCR won 22.2%, PRO won 12.1% and the Front for Victory won a humiliating fourth-place finish with just 10.9%.

In Santa Fe province, which borders both Buenos Aires and Córdoba, a special province-level coalition among the PS, UCR and other parties, the Frente Progresista Cívico y Social (FPCyS Progressive, Civic and Social Front) won 41.1%, the right-wing PRO won 25.9% and the Front for Victory just 21% in third place.

In western Mendoza province, the UCR won 44.1% to 26.5% for the Front for Victory, with a province-level leftist coalition winning 7.6%.

You have to look to the country’s fifth-most populous province, Tucumán, to find a first-place victory for Kirchner, where the Front for Victory won 45.8% to just 27.1% for a UCR-Socialist coalition. In Santa Cruz, Néstor’s Patagonian base, the party won just 22.9%, barely outpolling the Justicialists, who were running separately, and far behind the 44.5% that the UCR-dominated Unión por Vivir Mejor.

2 thoughts on “Peronist party, Fernández de Kirchner face insurrection even as opposition remains divided”