Like most folks who have no really strong feelings about the British monarchy (I’m neither incredibly pro-monarchy or anti-monarchy as far as constitutional monarchies go these days), I spent much of the past two days avoiding the coverage surrounding the birth of the royal prince born Monday to Prince William and Kate Middleton. ![]()

But Dylan Matthews, over at The Washington Post‘s Wonkblog, used the opportunity of the young (as yet unnamed) prince’s birth to make the case that constitutional monarchies are preferable to republics with elected heads of states, and that is a question in which that Suffragio readers ought to be incredibly interested. It’s a piece I read with keen excitement, it makes some very smart points, and it makes this rather sweeping conclusion:

Constitutional monarchy is the best form of government that humanity has yet tried. It has yielded rich, healthy nations whose regime transitions are almost always due to elections and whose heads of state are capable of being truly apolitical. The U.S. would do well to adopt it.

The punchline is that a constitutional monarchy is preferable to a republic with an elected, ceremonial head of state. That’s because a monarch’s position is not rooted in any legitimate political process, unlike a president who is elected either directly by ballot or indirectly by a national parliament — when political crises arise, a monarch is less likely to intervene in political affairs, thereby resulting in new elections; in contrast, an elected president is more likely to engineer a new government without new elections:

The key to monarchs’ success is that they’re totally illegitimate. The people wouldn’t stand for Queen Elizabeth exercising real political power just because of who her father was. That’s a powerful deterrent that prevents monarchs from meddling in political affairs. The result is that in all but very rare cases, prime ministers in monarchies are never thrown out of office except when they call elections or when they receive a vote of no confidence in parliament. The head of state can’t touch them.

It’s an interesting thesis, but I’m not sure that it holds up nearly as well as Matthews thinks it does.

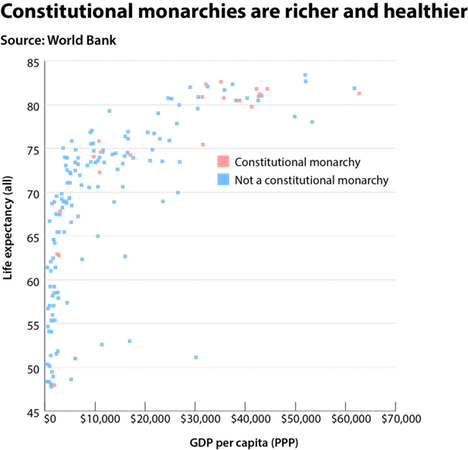

He begins with what I believe is the weakest argument of all — that constitutional monarchies are healthier and richer than other republics, and he presents a graph that purports to show that, on average, constitutional monarchies are richer and healthier (see below the chart from Wonkblog):

But of course, ‘correlation does not equal causation.’

There are a lot of historical and economic reasons that explain why constitutional monarchies, which are predominantly located in Europe, are so much richer and healthier. North America and Europe are, well, richer than Africa or the Middle East or South America, in general terms, but it seems like ‘having a constitutional monarchy’ is not incredibly high on the list of reasons why Europe’s standard of living is so much higher than Africa’s. The legacy of colonialism, for one.

After making this correlation, Matthews then backs off the claim somewhat:

Of course, this doesn’t demonstrate that having a constitutional monarchy makes countries richer, only that it’s totally possible to both be a healthy, rich country and be a constitutional monarchy. The practice is hardly a “grotesque relic.”

Still, the chart that states ‘constitutional monarchies are richer and healthier’ is not subtle, and I’m sure Matthews doesn’t mean to argue that Nicaragua or Paraguay or Kyrgyzstan would today have a GDP per capita of $40,000 if only they had introduced monarchies a century ago. Nor do I believe Matthews would defend the absolute monarchy of Swaziland, which boasts the world’s highest HIV/AIDS rate and where GDP per capita routinely falls even below that of neighboring South Africa. Is Swaziland better off today from the benevolence of King Mswati III? I don’t find that argument credible.

Thereupon, Matthews points to countries like Germany, Italy, Israel, Ireland, and India, which all have elected, mostly ceremonial, presidents:

Opponents of constitutional monarchy often point to this as their preferred alternative. The British group Republic supports abolishing the monarchy and replacing it with a directly elected president, and estimates that the British royal family costs almost ten times as much as the German president. So why not just do that, then?

But that sets up a false equivalency — at one point, Matthews writes, ‘ If Britain chose to depose its divinely ordained rulers, it’d still need a head of state.’

And that’s just not true. There’s no theorem of international relations that requires a parliamentary system to have a separate head of state. Matthews notes that only the sultans of Brunei and Oman simultaneously serve as prime minister. But in the United States, the president also essentially serves as the simultaneous head of state and head of government (unless you’d like to argue that John Boehner, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, or Harry Reid, the U.S. Senate majority leader, are the heads of government, though I think it would be a difficult argument). In any event, even if we don’t particularly prefer the Bruneian or Omanese models, it doesn’t mean that it’s a bad model from an abstract governance standpoint.

The only rationale in favor of having a ceremonial head of state is for purposes of national unity. In Spain, for example, the return of Juan Carlos I was an important step in the transition from the Franco dictatorship to robust democratic Spanish state we recognize today. But that example isn’t theoretical, it’s grounded in time and place to specific historical events, and it doesn’t provide a rationale for any other European monarch or ceremonial president, least of all in the United Kingdom. The existence of the British monarchy hasn’t stopped the push for devolution and even independence in Scotland, for example, and there’s no reason to believe an elected president would make any difference.

Matthews disregards the somewhat bland case that monarchies help boost tourism income (though if the UK needs the economic boost from selling tickets to Buckingham Palace at £19 a pop, it has deeper problems). He also notes that although the British monarchy is a costly institution, some monarchies, such as those in Spain, Sweden, Denmark and others are more frugal, with costs essentially equivalent to (or lesser than) those of an elected president.

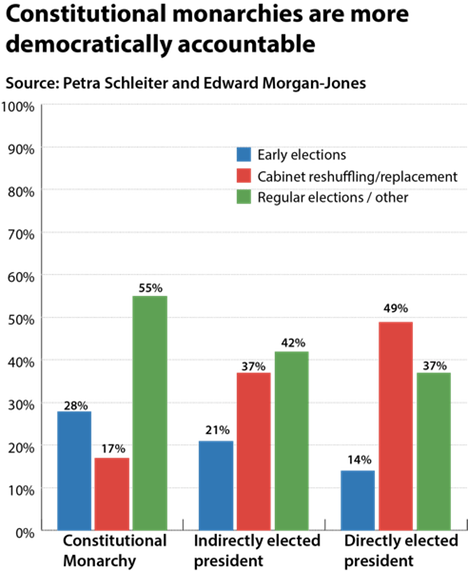

The real heart of the pro-monarchy argument is more intriguing, and the research Matthews cites is equally fascinating. Oxford political scientists Petra Schleiter and Edward Morgan-Jones have demonstrated that when a government falls in a constitutional monarchy, new elections are more likely than in countries with elected presidents. Furthermore, when a government falls in a country with an indirectly elected president, new elections are also more likely than in countries with directly elected presidents (again, here I’m dependent on Wonkblog’s chart):

From the outset, let’s look at the green line on the chart — fixed elections.

The decision of a country to hold fixed-term elections for a parliament need not be determined by whether the country has a monarch or an elected president. Though it’s still relatively rare, Norway (a constitutional monarchy) and Switzerland (a republic with an elected president) both have fixed-term parliaments, the European Parliament (a hydra-headed executive) is elected every five years, and Germany has a somewhat semi-fixed system. UK prime minister David Cameron’s government introduced a law in 2011 that purports to set elections to the British Parliament every five years, but the impetus for the change to British electoral law came from his coalition partners, the Liberal Democrats, not because the United Kingdom has Queen Elizabeth II instead of President Elizabeth Mountbatten-Windsor.

Now look at the relationship between just the blue lines and the red lines — it is pretty clear that as you move from a constitutional monarch to an indirectly elected president to a directly elected president, the outcome of a political crisis is a reshuffle or a replacement rather than new elections.

Fine, but what’s so great about snap elections all the time anyway? By way of example, just this week, Portuguese president Aníbal Cavaco Silva made a rather ham-fisted attempt to stitch up a grand coalition to govern Portugal until the end of its bailout program next June. Though he failed in that attempt, the center-right government will reconstitute itself much as before, with a few key personnel changes. Would it have been better if Portugal had gone directly to elections?

The result would have probably been one of three outcomes:

- The opposition, leading by double-digits in polls, would have won and Portugal will have had three prime ministers in three years. That’s hardly a recipe for thoughtful and stable policymaking at a time of extreme economic distress.

- The emergence of far-left groups and other parties would have splintered the vote so much that a hung parliament emerges, leading to possibly months of (not exactly democratic) horse-trading and negotiating before the formation of a new government, leaving Portugal (and Europe) paralyzed, again (ahem) at a time of extreme economic distress. That’s exactly what happened in Italy earlier this year, and it’s doubtful that the presence of an Italian monarchy would have changed that.

- The vote would have been so splintered that no government emerges, and Portugal would have been forced to hold yet another election this year, leaving the country with no hope of an organized government for months, again, it bears saying, at a time of extreme economic distress. That’s exactly what happened last year in Greece that brought the country as close as it has ever been to leaving the eurozone. Again, it seems unlikely that the outcome would have changed much if Greece had a monarchy.

None of those outcomes seem so much better than the actual outcome in Portugal this week — a government that was elected 24 months ago, and which is predictably unpopular after 24 months of tax increases and budget cuts, will trudge on in office through crucial months ahead.

Moreover, it’s not clear that elected presidents shouldn’t have more power precisely because they are elected, either directly or indirectly. For the same reasons that much of the modern world operates through representative democracy rather than the direct democracy of Greek city-states, perhaps some countries prefer the relative stability that comes from government reshuffles instead of the relative instability of more frequent elections.

And, of course, not all heads of state are created equally. Even within the realm of ceremonial presidents (as opposed to presidential republics where real power is vested in the president, such as in the United States or even France), not all presidents are created equally. The Czech presidency is designed to provide the head of state with relatively more muscular powers than, say, the German or Israeli presidency. Matthews himself notes that the indirectly elected president in Estonia acts in a much more political manner than the directly elected Irish president — in recent years, Mary Robinson and Mary McAleese ran as independents with no real ties to existing Irish political parties. If the body of ‘directly elected presidents’ were comprised solely of countries like Ireland, the research might indicate another outcome. So ultimately, the inescapable conclusion is that any country’s experience with a particular system may have much more to do with the country’s unique national and cultural qualities.

That doesn’t even begin to scratch the surface of the issue of countries like Canada. Although Canada is a constitutional monarchy, Canada has an appointed governor-general who serves as the royal representative in Canada — in effect selected by the prime minister, though technically appointed by Queen Elizabeth II. That makes the governor-general more like an indirectly elected president than a monarch. In recent years, the Canadian trend has been to appoint non-partisan governors-general, alternating anglophone and francophone, such as academic David Johnston and his predecessor, former journalist Michaëlle Jean, instead of blatantly political figures. Would Canada somehow have fewer reshuffles and more responsive government if Queen Elizabeth II served directly without a governor-general? It seems doubtful to me.

Constitutional monarchies may indeed be a fine form of government, but it’s a stretch to argue that they are clearly superior to parliamentary republics with elected presidents, because whether you think one form is superior will depend on whether you favor a government’s relative stability or responsivity to public opinion.

Photo credit to Annie Leibovitz.

CORRECTION: The original version mistakenly stated that Mitch McConnell was the U.S. senate majority leader — unless the Republican caucus has suddenly gained five seats, it is still Democratic senate leader Harry Reid.

Harry Reid is the Senate Majority leader.