No one quite personified post-war, ‘First Republic’ Italy more than Giulio Andreotti.![]()

Andreotti’s death today, at age 94, ends a career that spanned from the 1950s well beyond the end of the ‘First Republic,’ through the collapse of the hegemony of Italy’s Democrazia Cristiana (DC, Christian Democracy), and well into the contemporary era as one of Italy’s ‘senators for life.’

Andreotti is being remembered today for his triumphs — seven times a prime minister, first in 1972 and for the final time in 1992, he represented Italy throughout the Cold War and affirmed Italy’s close ties throughout the post-war years with the United States.

‘Divo Giulio‘ (Divine Julius) to his supporters and Belzebú (Beelzebub) to his opponents, Andreotti and his legacy remain just as complicated in death as in life, and his career’s ups and downs coincided with some of Italy’s most traumatic national tragedies, and it’s impossible to judge his career in the context of today’s political climate, but rather of the climate of post-war Italy, where tensions ran strong following a civil war between partisans and fascist supporters that settled, only over decades, into the broad left and right of today’s Italian politics.

His life inspired a 2008 biopic, Il Divo, that helped explain the Byzantine nature of post-war Italian politics to an international audience, and he presided over an era that saw Italy transformed from a country ravaged by war and 20 years of Benito Mussolini’s fascist rule into one of Western Europe’s strongest economies and a member of the G-7 group of world economies. At a time when the rest of southern Europe remained under the thumb of right-wing and military dictatorships and eastern Europe remained behind the iron-curtained influence of the communist Soviet Union, Andreotti and the Christian Democracy that he personified led Italy to a period of economic prosperity and pluralistic democracy, however imperfect.

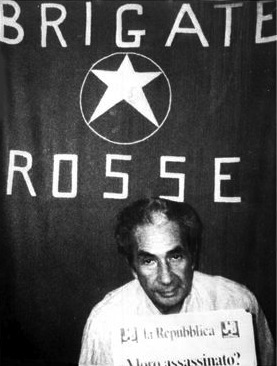

The most traumatic of those imperfections includes the kidnapping and assassination of his more leftist Christian Democratic friend and colleague, Aldo Moro, who served as prime minister in the 1960s and again from 1974 to 1976. The performance of the Partito Comunista Italiano (PCI, Italian Communist Party) in the 1976 elections had reached its highest level in Italian history, and Moro (pictured below), among others, turned to an unprecedented coalition with the PCI. Moro, however, was abducted on the streets of Rome in March 1978 by the leftist terrorist group, the Brigate Rosse (Red Brigades).

As prime minister once again, Andreotti refused to negotiate with Moro’s kidnappers, despite pleas from many within even his own government and from Moro himself. By May 1978, Moro had been killed and his corpse thrown in an old car, and Andreotti himself was the recipient of charges of incompetence, at the least, and malfeasance, at the worst, in letting political motivations override the priority of securing the release of a popular Italian political leader. DC-PCI cooperation ended — for good — shortly thereafter, much to the delight of the DC’s more right-wing members and to the delight of Italy’s American allies. Though the assassination took place 35 years ago, key questions about Moro’s death remain unanswered amid a web of conspiracy theories and the revelation of other programs — such as the existence of NATO’s Operation Gladio, a ‘stay-behind’ anti-communist operation in post-war Italy and the existence of the shady, Masonic lodge Propaganda Due (‘P2’) to which much of Italy’s post-war political elite belonged.

Throughout his career, Andreotti, like many of his Christian Democratic colleagues, was certainly no fool about the corrupt bargain that brought Sicilian votes to his party in exchange for a tacit acquiescence to Mafia dominance in southern Italy. Though Andreotti belatedly led an anti-Mafia campaign in his final years as prime minister, it wasn’t enough to prevent his own trial for Mafia collaboration (including with respect to the murder of a journalist, Mino Pecorelli, who was investigating Moro’s death).

Although Andreotti himself was never sullied by the Tangentopoli (‘Bribesville’) scandal that brought down the entirety of Italian political elite in 1992 and 1993, the system of patronage that he developed from the 1950s onward within Christian Democracy enabled the corruption that infected Italy’s politics. One of the reasons for that, perhaps, was that he receded during the 1980s as Bettino Craxi, the leader of the Partito Socialista Italiano (PSI, Italian Socialist Party) took the reins of power. Craxi presided over an era of economic bo0m, the era of ‘il sorpasso‘ (Italy, in this case, was surpassing the United Kingdom in terms of GDP per capita, however fleeting), but also an era of high public spending and the accumulation of public debt that continues to cripple Italian finances to this day. As Craxi’s foreign minister, Andreotti took on a role as an international consigliere, even as Craxi inched away from the United States and toward the emerging Arab world. Though Andreotti did not today a martyred hero like Moro, neither has he died in disgrace like Craxi, exiled as he was for the final seven years of his life in Tunisia.

Always close to the Vatican, Andreotti’s ties and influence remained strong throughout the 1990s and 2000s, notwithstanding his legal troubles. He helped play a role in bringing down Romani Prodi’s center-left government in January 2008, after abstaining to vote in favor of Prodi in the Senato, the upper house of Italy’s parliament, leading to Prodi’s resignation and the 2008 elections that returned Silvio Berlusconi to power — according to some, over Vatican disapproval of the Prodi government’s enthusiasm for same-sex marriage.

So what to make of Andreotti today?

You would expect no one to be more of an Andreotti cheerleader than Pier Ferdinando Casini, the leader of the Unione di Centro (UdC, Union of the Center), a small centrist party that’s heir to the once-dominant Christian Democracy and which supported former prime minister Mario Monti in February’s parliamentary elections. His remarks earlier today, far from being hagiographic, capture the nuance of a leader with the dexterity to remain at the heart of Italian power for six decades:

Giulio Andreotti è stato la Democrazia Cristiana, pur non essendo stato mai stato segretario della Democrazia Cristiana… Andreotti è stato la politica: ha condensato il bene e il male. Una personalità straordinaria. Uno statista internazionale conosciuto in tutto il mondo. Un cattolico vero. Un grande statista che ha sempre creduto nelle istituzioni.

[Giulio Andreotti was Christian Democracy itself, even though he was never actually the state secretary of Christian Democracy… Andreotti was politics itself, condensing both its good and bad. An extraordinary personality. An international statesman recognized globally. A true Catholic. A grand statesman who has always believed in institutions.]