Though the snap Venezuelan presidential election — just six days away — will likely have huge implications for the country’s economic policy, and though most economic commentators would agree that Venezuela is in dire need of economic reform, neither candidate seems especially keen on discussing those reforms in a campaign that’s been heavy on personality and emotions.![]()

But the negative aspects of legacy of chavismo — a growing public sector and nationalized industries, ever-expanding army of bureaucrats, widespread power outages, crumbling infrastructure — sound an awful lot like much of the problems that the United Kingdom faced in the late 1970s.

Is Venezuela entering its own ‘winter of discontent?’ And if so, does it need a Margaret Thatcher?

When it comes to South America, Thatcher is most well-known for the Falklands War against Argentina in 1982 (see Thatcher pictured above during that war).

But one Venezuelan blogger has already argued that Romuló Betancourt, the first democratically elected president of Venezuela in 1958, was its ‘Thatcher.’ Betancourt’s major contribution was normalizing democratic elections and peaceful transfers of power, an institution that has so far continued in Venezuela without interruption, even throughout the chavismo era. Economically, the Betancourt government’s most notable achievement was land reform that boosted rural peasants.

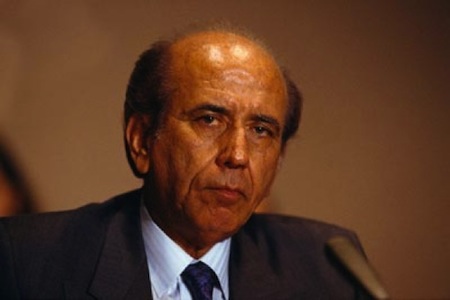

Perhaps the better example of Thatcherite economics in Venezuela is the second term of Betancourt’s successor (and one-time interior minister) Carlos Andrés Pérez (pictured below). Despite presiding over the largesse of the oil bonanza that to the rest of the world was an oil crisis, Pérez (or ‘CAP’) returned to office with high hopes that he could unlock another era of plenty on a relatively populist campaign built on empty promises.

Upon election, he rapidly sought a $4.5 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund, in return for crushing reforms that included a tax overhaul, a reduction in tariffs and custom duties and privatizations of state-owned companies. But those reforms (the ‘paquete‘ or the ‘package’) most controversially caused the price of gasoline prices to rise (and the secondary price of public transportation) due to the elimination in Venezuela’s famous gasoline subsidy — to this day, Venezuelan gas prices are the lowest in the world, and Venezuelans believe cheap gas is practically a birthright.

The reforms led directly to the Caracazo riots in Caracas on February 27, 1989 — as Francisco Toro and Juan Cristobal Nagel write in their wonderful compilation of 10 years of blogging about chavismo (from an opposition viewpoint), the Caracazo marked an incredible rupture in Venezuelan life:

Until then, Venezuelans had seen themselves as different, more civilized, more democratic, better than their Latin American neighbors. Thirty-one years of unbroken, stable, petrostate-funded democracy had made us terribly cocky. In a sense, the riots market Venezuela’s re-entry into Latin America. The country was no longer exceptional: just another hard-up Latin American country struggling to put its democracy on a stable footing.

Those riots ultimately led to the dismantling of Venezuela’s two-party system, CAP’s impeachment in 1993, and two coup attempts in 1992 — one in February 1992 by a little-known lieutenant colonel named Hugo Chávez, who would of course take power by democratic means just six years later in a landslide election victory.

So if Thatcherite policies ultimately paved the way for chavismo, could chavismo pave the way for a countervailing turn back to neoliberal reforms? Fast-forward two decades, and the country with the world’s largest proven reserves of petroleum finds itself with a budget deficit last year that equalled 17% of GDP and a public debt burden that’s now equal to 50% of GDP. So if he wins the presidential election, Chávez’s anointed successor Nicolás Maduro will have far fewer economic tools at his disposal than Chávez did to achieve his goals.

Opposition candidate Henrique Capriles certainly isn’t going around the country advocating the elimination of gasoline subsidies, but Capriles seems far likelier than Maduro to enact the kind of policy reforms that could balance Venezuelan finances back toward a more stable equilibrium.

But say what you will about the positive aspects of chavismo in reducing poverty in Venezuela and giving voice to a largely forgotten underclass excluded from the country’s oil wealth for a half-century, Venezuelan finances are hardly in great shape, and the winner of Sunday’s election will face significant financial pressures — all the more so if oil prices fall over the next six years.