Security experts — including Julianne Smith, deputy national security advisor to U.S. vice president Joe Biden — gathered at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies Thursday to discuss transatlantic security from Mali to Afghanistan.![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Among the newest issues on the transatlantic security agenda in the wake of France’s seemingly successful military incursion into northern Mali last month, is how NATO, the European Union, the United States and, increasingly, the African Union, can facilitate a lasting peace in the region. Indeed, atlantic-comminity.org, a transatlantic online think tank, is engaging a week-long ‘theme week’ on security in the Sahel.

From Mali to …?

But even as the world — from Paris to Washington to Bamako — celebrates the liberation of Timbuktu and other key northern Malian cities from al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) and other Islamic radical groups, tough questions remain about how to repair Mali, which still must arrive upon a peaceful settlement with Tuareg separatists in the north and return back to its peaceful, democratic path.

Even tougher questions remain about how to prevent another problem in any of the other countries in the Sahel — it’s not hard to draw a line between the influx of NATO-provided arms to Libya in 2011 and 2012 and the increasing instability in northern Mali. It’s not hard to imagine that the French military success so heralded today in Mali could become the catalyst that causes, say, 2014’s crisis in Mauritania. Or really any number of shaky nation-states in the western Sahel, from Mauritania to Chad. Or southern Algeria. Or, even worse, a relatively peaceful and stable west Africa.

Sarah Cliffe, a United Nations assistant secretary general for civilian capabilities, compared it to the regional problem in Central America in the 1980s — success in one country would result in another problem bubbling up in another country. She argued that a regional solution is indeed necessary, primarily through political and security means and thereafter through economic means.

Hans Binnendijk, a senior fellow at SAIS’s Center for Transatlantic Relations, argues that Mali represents one of three kinds of transatlantic action:

- the most formal approach, an ‘all-in’ response from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (i.e., a response based on the Washington Treaty’s Article Five that states that an attack on one NATO member is an attack on all NATO members), as has been the case with the NATO action in Afghanistan since October 2001;

- a less formal approach is a kind of ‘coalition of the willing’ among NATO members to take action, as was the case in the NATO-led assistance provided to Libyan rebels in the service of ousting longtime rule Muammar Gaddafi;

- in contrast, the Malian approach was even more ad hoc, because one nation (France) simply acted because Mali’s government was running out of time.

James Townsend, deputy U.S. assistant secretary of defense for European and NATO policy, argued that Mali has become a laboratory for transatlantic security, in terms of providing an example for how transatlantic responses to crises may be organized in the future, noting that we’ll see more crises like Mali (though it’s hardly clear that the French leadership, already concerned about the taint of Françafrique, has much of an appetite for becoming a near-permanent military presence throughout its former African colonial empire).

Townsend is probably right, but his remarks reminded me of the old adage — if all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

That’s to say that military and security responses to Mali can only achieve a limited amount of success without economic development and political engagement — and it’s not clear that transatlantic allies have much, if any, strategy for Mali, let alone the Sahel, where military force can’t resolve the issues of, for example, how to bring Tuareg rebels to the table to build a stable version of the Malian state, how to approach water policy and climate change in the Sahel in light of more frequent droughts, how to end human slavery in Mauritania, how to address the Darfur refugees that remain in Chad, or how international institutions can facilitate the development 21st century Sahelian economies.

It’s great that AQIM has been ousted from Timbuktu, but what long-term relief can we take from a ‘whack-a-mole’ strategy that shifts the threat from country to country, year after year?

The role of U.S. defense spending

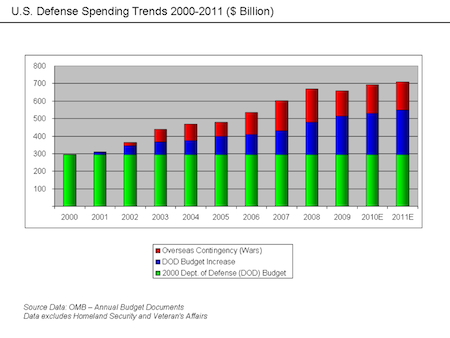

Townsend represents a U.S. defense regime with a budget has more than doubled since 2000:

U.S. military spending, even in light of the current budget-conscious trends of U.S. defense secretaries Robert Gates and Leon Panetta and newly appointed U.S. defense secretary Chuck Hagel, remains gargantuan — even if sequestration cuts take effect, defense spending will exceed $600 billion in fiscal year 2013 and U.S. president Barack Obama’s budget requested spending in excess of $725 billion. That doesn’t even take into account military retiree costs (around $30 billion) and homeland security spending (around $45 billion). The U.S. defense budget accounts, in fact, for between 40% and 45% of global defense spending, dwarfing by five-fold the most proximate such budget, that of the People’s Republic of China.

U.S. military spending, even in light of the current budget-conscious trends of U.S. defense secretaries Robert Gates and Leon Panetta and newly appointed U.S. defense secretary Chuck Hagel, remains gargantuan — even if sequestration cuts take effect, defense spending will exceed $600 billion in fiscal year 2013 and U.S. president Barack Obama’s budget requested spending in excess of $725 billion. That doesn’t even take into account military retiree costs (around $30 billion) and homeland security spending (around $45 billion). The U.S. defense budget accounts, in fact, for between 40% and 45% of global defense spending, dwarfing by five-fold the most proximate such budget, that of the People’s Republic of China.

Accordingly, it’s worth asking whether the U.S. defense behemoth is now designed in a way that incentives seeking out new crises (or, perhaps seeking out new theaters in ongoing crises) rather than solving an existing threat in a holistic way.

Even as the actors in transatlantic security increasing look at ever wider coordination, it’s ironic that the target of those security coordination efforts are addressed on incredibly narrow terms, a nearsighted ‘crisis-by-crisis’ approach that focuses on discrete nations.

As Derek Catsam advises in a piece this week for atlantic.community.org:

Don’t lead with military solutions, and do not presume that the most important issues in the Sahel are related to questions of terrorism or radical Islamic fundamentalism. These are oftentimes American and Western concerns. Policies need to be more visionary and far-reaching. Believe it or not, in the vast majority of Africa, including many parts of the Sahel, terrorism is not one of the ten most important issues people face, never mind being the central issue. America’s War on Terrorism has warped foreign policy almost to the breaking point.

Cliffe, nearly alone among the SAIS conference’s participants, argued for the necessity of a regional approach, and also admitted that Mali’s resources are so small that it will be difficult for the Malian state alone to provide the kind of government resources that will be necessary to unite the country in the short-term. She cautioned, however, that experiences in Iraq and Afghanistan taught international groups that even if there’s a coherent strategy at the transatlantic and supranational level, the effort won’t succeed unless the country’s internal leaders take ownership of those priorities.

Four potential new ‘bubbles’ — Mauritania, Chad, Niger and Burkina Faso

What today is the 2013 Malian crisis and what tomorrow could be the 2015 Chadian or Mauritanian or Nigerien crisis are really the same issue — longstanding economic underdevelopment and political insecurity. It’s incredibly unclear that transatlantic allies have a regional security solution to the problem, to say nothing of a political and economic strategy.

What should frighten transatlantic policymakers most of all is that Mali was by far the most stable of the countries in the western Sahel — after all, it had experience with peaceful transfers of power, free and mostly fair elections, a free press and some amount of economic development. So what happened in Mali can happen in any of its neighbors.

Mauritania

I wrote earlier this year about the risks for Mauritania, in particular. A former French colony like Mali, Mauritania to its west is also a very poor, predominantly Muslim country featuring an ethnic north/south split. Though current president Mohamed Ould Abdelaziz has taken a relatively aggressive stand against radical Islam, it’s not clear that he could necessarily stop an AQIM influx over a vast territory that’s larger than France and Germany together.

Unlike Mali, Mauritania doesn’t have any tradition of democratic government, lurching instead from one military government to the next since independence — Abdelaziz himself took power in a coup in 2008. Mauritania remains one of the holdouts through the entire world in that human slavery is still widely practiced, despite some legal progress in the past couple of decades.

But AQIM and other radicals could just as easily destabilize Niger, Chad or Burkina Faso, each of which also gained independence in 1960 from France.

Chad

Chad, the fifth-largest country in Africa, has an even more complicated demographic profile, with many different ethnic groups, including nomadic Arabs, such as the Toubou ethnic group in the north, and tribal sub-Saharan societies, such as the Sara ethnic group, in the south. The country is about 55% Muslim, 35% Christian, and 10% animalist. Recent discoveries of oil wealth could bring additional development, though it could also bring the perils of the ‘resource curse’ that have plagued countries with far stronger governing and economic institutions. Like in Mauritania, power is acquired and held through less than democratic means — Idriss Déby took power in 1990 and has won each subsequent ‘election.’

Despite the discovery of oil in 2003, Chad found itself drawn into Sudan’s violent troubles in the 2000s, and it still harbors over 250,000 refugees displaced from the horrific violence in Darfur, causing a number of humanitarian problems, including not only threats to security, but the ongoing risk of famine, dehydration and disease. Those risks have been exacerbated by drought — the 2012 Sahelian drought in particular reduced the annual Chadian crop yield by up to 50%.

In 2008, northern rebels mounted a strong attack upon Déby’s government, and, as in Mali, the French military helped the Chadian government push back an assault on its capital, N’Djamena.

Niger

Mali’s northeastern neighbor, Niger, with 16 million people, is slightly more populous than Mali itself, and even poorer — it’s one of the least developed countries in the world, and poverty, illiteracy and disease remain widespread. Although like Mali it is predominantly Muslim, it’s also been plagued with Tuareg insurgency in its north. Its president, Mahamadou Issoufou, was elected in a January 2011 presidential race following a military coup — one of many since independence — that ousted the former president.

Niger is hoping exploration will, as in Chad, result in the discover of the kind of oil wealth that could bring some well-needed development. Like Chad, Niger was one of the most badly affected by the 2012 Sahelian drought.

Burkina Faso

Burkina Faso, Mali’s more southeastern neighbor, has the largest population (17 million) and the largest economy in the Sahel, though it remains one of the world’s poorest countries on a per capita basis. Like Chad, its population adheres to both Islam and Christianity.

Many of the problems that feature throughout the rest of the Sahel feature in Burkina Faso, including a longtime president, Blaise Compaore, who took power by force in 1987, and a lack of social, democratic and economic development.

The path forward

The lack of transatlantic focus on economic development is especially incredible in light of what we’ve learned over the past decade in Afghanistan — the United States has spent routinely in the past four years well over $100 billion in a country that, even today, has a gross domestic product of just $30 billion, as of 2011, and it’s not clear that American troops will leave Afghanistan next year with the country in significantly better shape than American troops found it 13 years ago.

The Sahel countries are, like Afghanistan, some of the poorest countries in the world, even at a time when Africa is starting to boom: Mali’s GDP is just $17 billion, Burkina Faso’s is $22 billion,Chad’s is $20 billion, Niger’s is $12 billion, Mauritania’s a tiny $7 billion — all of which are rounding errors in the U.S. defense budget, and taken together, their combined economies don’t total much more than the amount of ‘sequestration’ budget cuts set to take effect on U.S. defense spending.

I’m certainly not a development policy expert, but it seems evident that security in the Sahel will not come through one military campaign in one region of one country — true security can only come from a multifaceted approach that includes not only traditional military power and peacekeeping forces, but which also devotes significant resources to ameliorating the following:

- lingering humanitarian concerns in Chad with respect to displaced Darfur refugees, as well as all of those people still suffering the effects of the 2012 Sahelian droughts;

- human rights deficiencies, including the continued horror of human slavery in Mauritania, but more generally with respect to promoting freedom throughout the entire region and facilitating the development of stable governments, the rule of law and democratic institutions;

- economic development throughout the Sahel, beyond the extraction of oil wealth in Chad (and perhaps Niger), but through the proliferation of transportation, communication and other infrastructural advances, the creation of more predictable and stable business environments and reduction in the incidence of corruption;

- social development in the region by means of promoting more education and literacy, and better health care facilities;

- climate change and water policy that addresses the frequency of drought, famine and crop failure throughout the Sahel; and

- a Tuareg political settlement that includes not only Mali’s longstanding National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad (MNLA), but also the more Islamist (but still home-grown) Ansar Dine and, perhaps, Niger’s Tuareg leaders and other northern Sahel groups as well.

Until we hear more about those kinds of policy priorities in discussions on both sides of the Atlantic, ever-cooperative transatlantic security efforts cannot and will not bear the ultimate fruit of a more secure Sahel.

Who is Ibrahim Boubakar Keïta?