The United Kingdom is closer to May 2015 than it is to May 2010, which is to say that it’s closer to the next general election than to the previous one.![]()

With the announcement of the 2013 budget coming later this month, likely to be very controversial if it features, as expected, ever more aggressive expenditure cuts, what does UK prime minister David Cameron have to show for his government’s efforts?

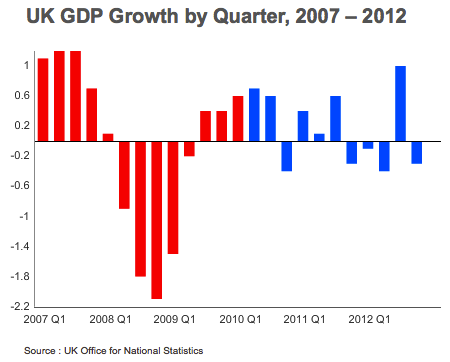

The prevailing conventional wisdom today is that Cameron and his chancellor of the exchequer George Osborne (pictured above) have pushed blindly forward with budget cuts at the sake of economic growth by reducing government expenditures at a time when the global economic slump — and an even deeper economic malaise on continental Europe — have left the UK economy battered. If you look at British GDP growth during the Cameron years (see below — the Labour government years are red, the Cameron years blue), it’s hard to deny that it’s sputtering:

One way to look at the chart above is that following the 2008 global financial panic, the United Kingdom was recovering just fine under the leadership of Labour prime minister Gordon Brown, and that the election of the Tory-led coalition and its resulting budget cuts have taken the steam out of what was a modest, if steady, economic recovery. Those cuts have hastened further financial insecurity in the United Kingdom, critics charge, and you need look no further than Moody’s downgrade of the UK’s credit rating last month from from ‘AAA’ to ‘AA+’ for the first time since 1978.

An equally compelling response is that British revenues were always bound to fall, given the outsized effect of banking profits on the UK economy, and that meant that expenditure corrections were inevitable in order to bring the budget out from double-digit deficit. In any event, 13 years of Labour government left the budget with plenty of fat to trim from welfare spending. Despite the downgraded credit rating, the 10-year British debt features a relatively low yield of around 2% (a little lower than France’s and a bit higher than Germany’s), and we talk about the United Kingdom in the same way we talk about the Netherlands, Belgium and Germany — not the way we talk about Iceland, Ireland, Spain, Italy or Greece. Given the large role the finance plays in the British economy, it wasn’t preordained that the United Kingdom would be more like France than, say, Ireland.

Nonetheless, polls show Cameron’s Conservative Party well behind the Labour Party in advance of the next election by around 10%, making Labour under the leadership of Ed Miliband and shadow chancellor Ed Balls, a Brown protégé, implausibly more popular than at any time since before former prime minister Tony Blair’s popularity tanked over the Iraq war. Despite Cameron’s ‘modernization’ campaign, which notched its first notable triumph with the recognition of same-sex marriage in February, over the howls of some of his more old-fashioned Tory colleagues, he remains deeply unpopular.

Meanwhile, the upstart and nakedly anti-Europe United Kingdom Independence Party — Cameron famously once called them a bunch of ‘fruitcases, loonies and closet racists’ — has grown to the point that it now outpolls Cameron’s governing coalition partners, the Liberal Democratic Party. UKIP even edged out the Tories in a recent by-election in Eastleigh, and Cameron has relented to calls for the first-ever referendum on the continued UK membership in the European Union (though, targeted as it is for 2017, it assumes that Cameron will actually be in power after the next election).

Nervous Tory backbenchers, already wary of local elections in May and European elections in 2014, are already starting to sound the alarms of a leadership challenge against Cameron, though it’s nothing (yet) like the kind of constant embattlement that plagued former Labour prime minister Gordon Brown.

Former Conservative prime minister Margaret Thatcher faced an even more dire midterm slump in the early 1980s and still managed to win the 1983 general election handily, but if the current Labour lead settles or even widens, political gravity could well paralyze the government in 2013 and 2014 in the same way as Brown’s last years in government or former Tory prime minister John Major’s.

It’s worth pausing to note what the Cameron-led coalition government has and has not done.

Upon taking office in 2010, Cameron pushed through an ’emergency’ budget aimed at bringing down public debt — the first June 2010 budget raised the UK value-added tax from 17.5% to 20%, added a new bank levy and raised the capital gains tax for the wealthiest taxpayers, while also implementing a two-year public sector pay freeze, accelerating the pension retirement age to 66, and scheduling an additional £17 billion in budget cuts through 2015. That budget still resulted in a £149 billion deficit, around 11% of UK GDP.

Subsequent budgets have shrunk the deficit to £90 billion in 2012 — still around 6% of GDP — despite a cut in corporate tax and the top income tax rate from 50% to 45% in the 2012 budget. Osborne and Cameron are looking to implement an additional round of welfare cuts by 2016 of up to £16 billion, acknowledging that they won’t eliminate the UK’s structural deficit within the span of the current parliament.

That continued shortfall — and the Moody’s downgrade — have caused Cameron and Osborne to double down, stoking expectations for deeper and faster cuts in advance of the 2013 budget announcement set for March 20, despite the fact that his own government’s business secretary Vince Cable, a Liberal Democrat, is publicly considering the possibility that the government should borrow more money to boost spending on infrastructure and other public investments and improvements:

The question throughout has been how to maintain the confidence of creditors when the government is having to borrow at historically exceptional levels, without killing confidence in the economy in so doing through too harsh an approach.

When the government was formed it was in the context of febrile markets and worries about sovereign risk, at that stage in Greece, but with the potential for contagion. There was good reason to worry that the UK, as the country arguably most damaged by the banking crisis and with the largest fiscal deficit in the G20, could lose the confidence of creditors without a credible plan for deficit reduction including an early demonstration of commitment.

Almost three years later, the question is whether the balance of risks has changed. The IMF argued last May that the risk of losing market confidence as a result of a more relaxed approach to fiscal policy – particularly the financing of more capital investment by borrowing – may have diminished relative to the risk of public finances deteriorating as a consequence of continued lack of growth.

Cable, however gently and eloquently, makes it pretty clear that he thinks the balance of risks has changed, though Cameron has already signaled that there’s about as much chance of additional stimulative borrowing as there is of appointing the members of One Direction to his cabinet.

It would take some time — probably a year or so — for any change in economic policy to be felt by the general public, so the window is rapidly closing for Cameron to reverse course in time for it to have any effect on the 2015 general election, but there’s absolutely no indication that he will do so. If anything, he’s accelerating.

Why the obstinacy?

Some of that is due, one hopes, to the notion that the incoming governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney (currently the governor of the Bank of Canada), is expected to take a more aggressive approach to monetary policy when he assumes office later in June — and it appears this week that Osborne is likely to give the Bank of England under Carney additional powers for monetary activism, so that’s a very encouraging sign for proponents of looser monetary policy.

Without getting too much into a side discourse about the relative merits of stimulative monetary policy over stimulative fiscal policy, Carney’s approach might not look too far from the argument that economist Scott Sumner made over a year ago:

I’m sorry to have to repeat this over and over again, but what 99% of pundits on both sides of the Atlantic are treating as a debate about “stimulus” and “austerity” is actually a debate about stupidity…. Don’t say “austerity will fail.” Say “austerity will work, but only if the BOE becomes much more aggressive, otherwise it will fail.”

Ultimately, however, I’d wager that Cameron simply believes that his approach has shielded the British economy — and will continue to shield the British economy — from the turbulence of investor sentiment.

It’s worth remembering that he cut his teeth as a top advisor to former chancellor Norman Lamont, who took much of the blame for the ‘Black Wednesday’ debacle in 1992, when currency speculators forced the British pound out of the European exchange rate mechanism, the ‘currency snake’ that was much the forerunner to the formal currency union that is today’s eurozone.

The defining moment that shaped Cameron’s early years in politics was a financial crisis forced on the United Kingdom from the ‘electronic herd’ of global investors — it’s not difficult to draw a line from that formative moment to the crusade that he and Osborne have waged since May 2010.

Photo credit to Chris Ratcliffe / Bloomberg.

Thanks for sharing us your wonderful page.