European and global stock markets whipsawed earlier this week as investors contemplated the notion of gridlock in Italy’s hung parliament following the weekend’s inconclusive vote, and what that means for the eurozone’s future.

![]()

![]()

Predictably enough, European leaders took turns to warn Italy not to veer from its austerity-minded course, and Germany’s hapless social democratic leader Peer Steinbrück even managed to insult Italy’s president by referring to center-right leader Silvio Berlusconi and protest leader and blogger Beppe Grillo ‘clowns.’

But as Italians turned to counting results from regional elections yesterday, there’s another threat looming on the horizon — the specter of separatism.

Even as the autonomist Lega Nord (Northern League) fell from 60 deputies to just 18 in Italy’s lower house, the Camera dei Deputati (House of Deputies), its leader Roberto Maroni (pictured above) won a hard-fought battle for control of Italy’s largest regional government on a slogan of ‘prima il Nord‘ — ‘the North first.’

That’s because, in addition to the general election, Italians in Lombardy, Lazio and Molise also went to the polls to elect their regional governments as well — it’s as if, on the day of the Canadian federal election, each of Ontario, British Columbia and Prince Edward Island each held their own provincial elections as well.

And there’s no bigger prize than Lombardy, the home of Milan, Italy’s financial, industrial and fashion capital, is Italy’s wealthiest region and its most populous as well — with 10 million people, one in six Italians is a Lombardian.

Maroni’s victory is pivotal because it now gives the Northern League control of the regional governments in Italy’s three largest, wealthiest regions, and Maroni has not hidden his ambitions for a more autonomous northern Italy. In the past two decades, the Northern League has alternated between supporting greater autonomy and supporting full independence for ‘Pavania,’ its term for northern Italy.

Maroni envisions a Europe of ‘regions,’ and a more federal Italian government that allows northern Italy to keep more of its revenues:

“If I win in Lombardy, a new phase will open: it’s about the path which leads to the creation of the macro-region, and in the same time the first piece of the new Europe of the Regions. It’s an ambitious project, which is not concerning the destiny of Lombardy only, but of the entire North. And it could change history: in Italy’s Northern regions and in Europe.”

That explains, in part, why Maroni was so enthusiastic to leave national politics for local politics — he took over as national leader only last year after long-time Northern League leader Umberto Bossi resigned amid corruption charges. Maroni has become a familiar face to all Italians over the past two decades — he served as minister of the interior in Berlusconi’s past 1994-95 and 2008-11 governments, and as minister of labor and welfare from 2001-06.

Initially, Maroni wants Lombardy to keep 75% of its total tax revenues, compared to around 66% of the tax revenues it retains currently.

Luca Zaia, the leader of the Liga Veneta (Venetian League), is the regional president of Veneto, where separatist support is strongest, having won the 2010 regional elections in Veneto in a landslide victory, heading a broad center-right coalition.

To the west of Lombardy, in Piedmont, support for the Northern League has traditionally been less enthusiastic — after all, the genesis of Italian unification in the 1860s was born in what was then the kingdom of Piedmont. Nonetheless, Roberto Cota won control of Piedmont’s government in the 2010 regional elections, leading a center-right coalition that very narrowly ousted the previous center-left Piedmontese government.

With a 2014 referendum on Scotland’s independence from the United Kingdom scheduled and an inevitable showdown between Catalunya’s president Artur Mas and the federal Spanish government over Catalan independence, Maroni’s consolidation of northern Italy under autonomist control means that northern Italy may become the next separatist domino to follow, especially as Italy’s economy continues through a brutal recession and its national government seems unable to take any measures to ameliorate economic decline (or, following this weekend’s election, take any measures at all).

So long after the current crisis recedes with respect to Italy’s national government, Maroni will be around for some time to come to cause headaches for the next Italian prime minister — even more so if it turns out to be a center-left prime minister, such as Pier Luigi Bersani, whose centrosinistra coalition, dominated by Bersani’s Partito Democratico (PD, Democratic Party), looks to form a stable government.

In some ways, Maroni’s victory is more stunning than the Northern League’s 2010 upset victory in Piedmont.

The Lombardy regional elections were supposed to give Italy’s center-left its first chance of victory in nearly two decades, after the resignation of a longtime powerbroker of Berlusconi’s Popolo della Libertà (PdL, People of Freedom), which put corruption at the heart of the campaign.

Roberto Formigoni, a former Christian Democrat and regional president since 1995, resigned in late 2012 over the arrest of one of his officials for allegedly buying votes in the 2010 regional elections from the ‘Ndrangheta — the local organized crime operation of Calabria. Formigoni, once a top leader in the Catholic political action group Communion and Liberation in the culture wars over marriage and divorce in the 1970s, is one of the truly old-school barons of the Italian right, and he’s one of the few who had seamlessly transitioned from the ‘first republic’ into the post-Tangentopoli ‘second republic’ that’s come to be dominated by Berlusconi, who’s also from Milan.

So the Lombardian election, as the heartland of Italy’s center-right, was always going to be an important prize in the weekend’s elections, regardless of the result of the national elections to the Italian parliament.

Given the fatigue with the scandal-plagued Formigoni administration, and also the relative decline of Berlusconi’s national reputation, the center-right backed Maroni as its regional candidate in the 2013 election.

Ultimately, however, the fragmentation of the electorate in Lombardy mirrored that of the national electorate.

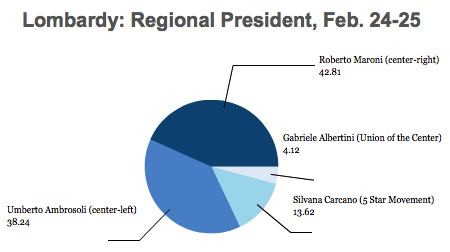

Maroni won 42.81% to 38.24% for the center-left’s candidate, Umberto Ambrosoli, the son of Giorgio Ambrosoli, an attorney assassinated in 1979 after investigating Michele Sindona, a Mafia-connected banker. That’s only a narrow victory for Maroni, and it’s much less than the 56% that Formigoni won in 2010.

Silvana Carcano, the candidate of Grillo’s populist Movimento 5 Stelle (M5S, the Five Star Movement) won 13.62%, and Gabriele Albertini, who served as the PdL-backed mayor of Milan from 1997 to 2006, won just 4.12% as the anti-corruption candidate of the centrist, Christian democratic Unione di Centro (UdC, Union of the Centre).

One way to look at Maroni’s victory is as a battle of the spoilers — Carcano won more than three times the support that Albertini won. Even if you assume Carcano pulled equally from the pool of center-right and center-left voters, Albertini pulled more from the center-right than the center-left.

Regional elections comprise two votes — one election for regional president and a proportional party vote to determine the composition of the regional parliament. The party vote is even more fascinating:

Although the broad Maroni-led coalition will control 49 seats in the 80-member regional parliament, a clear majority, the ‘Maroni’ list and the Northern League will together hold 27 seats, a good deal more than the PdL, which won only 19 seats. That’s already causing tension between Maroni’s lieutenants and Formigoni’s old guard as they divide up the spoils of victory.

Although the broad Maroni-led coalition will control 49 seats in the 80-member regional parliament, a clear majority, the ‘Maroni’ list and the Northern League will together hold 27 seats, a good deal more than the PdL, which won only 19 seats. That’s already causing tension between Maroni’s lieutenants and Formigoni’s old guard as they divide up the spoils of victory.

The center-left coalition will hold 22 seats and the Five Star Movement nine seats.

One thought on “Maroni’s Lombardy victory consolidates Northern League’s regional hold”